1300–1400 in European fashion

Costume historian James Laver suggests that the mid-14th century marks the emergence of recognizable "fashion" in clothing,[1] in which Fernand Braudel concurs.

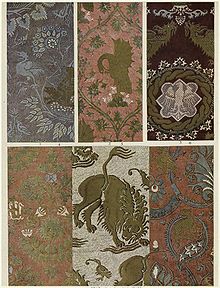

Trade in textiles continued to grow throughout the century and formed an important part of the economy for many areas from England to Italy.

[9] A fashion for mi-parti or parti-coloured garments made of two contrasting fabrics, one on each side, arose for men in mid-century,[10] and was especially popular at the English court.

[11] Fur was mostly worn as an inner lining for warmth; inventories from Burgundian villages show that even there a fur-lined coat (rabbit, or the more expensive cat) was one of the most common garments.

[15] Hose or chausses made out of wool were used to cover the legs, and were generally brightly colored, and often had leather soles, so that they did not have to be worn with shoes.

[15] The shorter clothes of the second half of the century required these to be a single garment like modern tights, whereas otherwise they were two separate pieces covering the full length of each leg.

A French chronicle records: "Around that year (1350), men, in particular, noblemen and their squires, took to wearing tunics so short and tight that they revealed what modesty bids us hide.

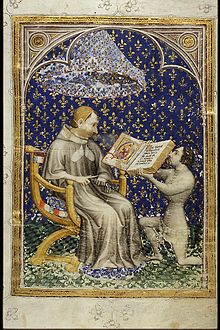

At this period, the most dignified figures, like King Charles in the illustration, continue to wear long robes—although as the Royal Chamberlain, de Vaudetar was himself a person of very high rank.

This abandonment of the robe to emphasize a tight top over the torso, with breeches or trousers below, was to become the distinctive feature of European men's fashion for centuries to come.

[19] The funeral effigy and "achievements" of Edward, the Black Prince in Canterbury Cathedral, who died in 1376, show the military version of the same outline.

[20] As an indication of the rapid spread of fashion between the courts of Europe, a manuscript chronicle illuminated in Hungary by 1360 shows very similar styles to Edward's English version.

Edward's son, King Richard II of England, led a court that, like many in Europe late in the century, was extremely refined and fashion-conscious.

He himself is credited with having invented the handkerchief; "little pieces [of cloth] for the lord King to wipe and clean his nose," appear in the Household Rolls (accounts), which is the first documentation of their use.

He distributed jeweled livery badges with his personal emblem of the white hart (deer) to his friends, like the one he himself wears in the Wilton Diptych (above).

During this century, the chaperon made a transformation from being a utilitarian hood with a small cape to becoming a complicated and fashionable hat worn by the wealthy in town settings.

[15] All classes and both sexes are usually shown sleeping naked—special nightwear only became common in the 16th century[26]—yet some married women wore their chemises to bed as a form of modesty and piety.

Over the chemise, women wore a loose or fitted gown called a cotte or kirtle, usually ankle or floor-length, and with trains for formal occasions.

When fitted, this garment is often called a cotehardie (although this usage of the word has been heavily criticized[27]) and might have hanging sleeves and sometimes worn with a jeweled or metalworked belt.

Over time, the hanging part of the sleeve became longer and narrower until it was the merest streamer, called a tippet, then gaining the floral or leaflike daggings in the end of the century.

[28] Sleeveless overgowns or tabards derive from the cyclas, an unfitted rectangle of cloth with an opening for the head that was worn in the 13th century.

Before the hennin rocketed skywards, padded rolls and truncated and reticulated headdresses graced the heads of fashionable ladies everywhere in Europe and England.

The barbet was a band of linen that passed under the chin and was pinned on top of the head; it descended from the earlier wimple (in French, barbe), which was now worn only by older women, widows, and nuns.