Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

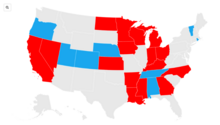

The exceptions were Kentucky and Delaware, and to a limited extent New Jersey, where chattel slavery and indentured servitude were finally ended by the Thirteenth Amendment in December 1865.

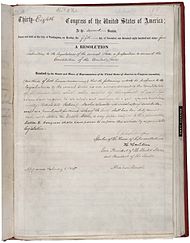

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Prior to the Thirteenth Amendment, the United States Constitution did not expressly use the words slave or slavery but included several provisions about unfree persons.

[6] Proposals to eliminate slavery by constitutional amendment were introduced by Representative Arthur Livermore in 1818 and by John Quincy Adams in 1839, but failed to gain significant traction.

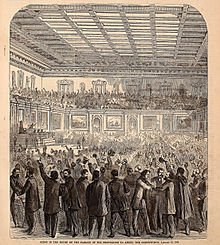

[10] Acting under presidential war powers, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, with effect on January 1, 1863, which proclaimed the freedom of slaves in the ten states that were still in rebellion.

[13] By December 1863, Lincoln again used his war powers and issued a "Proclamation for Amnesty and Reconstruction", which offered Southern states a chance to peacefully rejoin the Union if they immediately abolished slavery and collected loyalty oaths from 10% of their voting population.

Radical Republicans led by Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner and Pennsylvania Representative Thaddeus Stevens sought a more expansive version of the amendment.

[22][23] The committee's version used text from the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which stipulates, "There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crimes whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.

[28] In the 1864 presidential race, former Free Soil Party candidate John C. Frémont threatened a third-party run opposing Lincoln, this time on a platform endorsing an anti-slavery amendment.

[53] Representative Thaddeus Stevens later commented that "the greatest measure of the nineteenth century was passed by corruption aided and abetted by the purest man in America"; however, Lincoln's precise role in making deals for votes remains unknown.

With a total of 183 House members (one seat was vacant after Reuben Fenton was elected governor), 122 would have to vote "aye" to secure passage of the resolution; however, eight Democrats abstained, reducing the number to 117.

With Congress out of session, the new president, Andrew Johnson, began a period known as "Presidential Reconstruction", in which he personally oversaw the creation of new state governments throughout the South.

[79] When South Carolina ratified the Amendment in November 1865, it issued its own interpretive declaration that "any attempt by Congress toward legislating upon the political status of former slaves, or their civil relations, would be contrary to the Constitution of the United States.

[110][111] Proponents of the Act, including Trumbull and Wilson, argued that Section 2 of the Thirteenth Amendment authorized the federal government to legislate civil rights for the States.

[115] However, the effect of these laws waned as political will diminished and the federal government lost authority in the South, particularly after the Compromise of 1877 ended Reconstruction in exchange for a Republican presidency.

[116] Southern business owners sought to reproduce the profitable arrangement of slavery with a system called peonage, in which disproportionately black workers were entrapped by loans and compelled to work indefinitely due to the resulting debt.

[119] These workers remained destitute and persecuted, forced to work dangerous jobs and further confined legally by the racist Jim Crow laws that governed the South.

[125] Under the leadership of Attorney General Francis Biddle, the Civil Rights Section invoked the constitutional amendments and legislation of the Reconstruction Era as the basis for its actions.

[129] Thomas Jefferson authored an early version of that ordinance's anti-slavery clause, including the exception of punishment for a crime, and also sought to prohibit slavery in general after 1800.

[137] In late 2020, Senator Jeff Merkley (D-OR) and Representative William Lacy Clay (D-MO) introduced a resolution to create a new amendment to close this loophole.

As historian Amy Dru Stanley summarizes, "beyond a handful of landmark rulings striking down debt peonage, flagrant involuntary servitude, and some instances of race-based violence and discrimination, the Thirteenth Amendment has never been a potent source of rights claims.

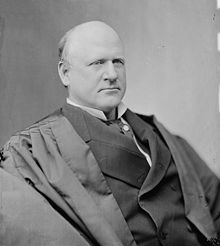

"[140][141] United States v. Rhodes (1866),[142] one of the first Thirteenth Amendment cases, tested the constitutionality of provisions in the Civil Rights Act of 1866 that granted blacks redress in the federal courts.

Kentucky law prohibited blacks from testifying against whites—an arrangement which compromised the ability of Nancy Talbot ("a citizen of the United States of the African race") to reach justice against a white person accused of robbing her.

"[155] In his solitary dissent, John Marshall Harlan (a Kentucky lawyer who changed his mind about civil rights law after witnessing organized racist violence) argued that "such discrimination practiced by corporations and individuals in the exercise of their public or quasi-public functions is a badge of servitude, the imposition of which congress may prevent under its power.

[152]Attorneys in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896)[157] argued that racial segregation involved "observances of a servile character coincident with the incidents of slavery", in violation of the Thirteenth Amendment.

It is clear, however, that the amendment was not intended to introduce any novel doctrine with respect to certain descriptions of service which have always been treated as exceptional, such as military and naval enlistments, or to disturb the right of parents and guardians to the custody of their minor children or wards.

[164] In Bailey v. Alabama the U.S. Supreme Court reaffirmed its holding that the Thirteenth Amendment is not solely a ban on chattel slavery, it also covers a much broader array of labor arrangements and social deprivations.

The Court said: The plain intention [of the amendment] was to abolish slavery of whatever name and form and all its badges and incidents; to render impossible any state of bondage; to make labor free, by prohibiting that control by which the personal service of one man is disposed of or coerced for another's benefit, which is the essence of involuntary servitude.

And when racial discrimination herds men into ghettos and makes their ability to buy property turn on the color of their skin, then it too is a relic of slavery.Negro citizens, North and South, who saw in the Thirteenth Amendment a promise of freedom—freedom to "go and come at pleasure" and to "buy and sell when they please"—would be left with "a mere paper guarantee" if Congress were powerless to assure that a dollar in the hands of a Negro will purchase the same thing as a dollar in the hands of a white man.

The Court ruled that seamen's contracts had been considered unique from time immemorial, and that "the amendment was not intended to introduce any novel doctrine with respect to certain descriptions of service which have always been treated as exceptional."