1570 Ferrara earthquake

It led to the establishment of an earthquake observatory which published to very high regard, and the drafting of some of the first-known building designs based on a scientific seismic-resistant approach.

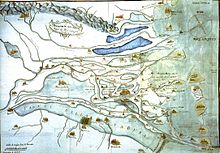

Information from hydrocarbon exploration demonstrates that the area is underlain by a series of active thrust faults and related folds, some of which have been detected from anomalous drainage patterns.

Ferrara was the location for minor earthquakes in the four centuries before 1570, these events being recorded in the city archives with detailed descriptions of damage to buildings and depositions by witnesses.

Despite continuous – and often victorious – wars against the age's superpowers, the nearby Venice and the Papal States, Ferrara in the 16th century was a thriving city, a major hub for trade, business and liberal arts.

World class music and painting schools, linked with Flemish artistic communities, were established in the late 15th and early 16th century, under the patronage of the House of Este.

A new part of the city, named Addizione Erculea (Erculean Addition) had been built in the previous century: it is commonly considered one of the major examples of urban planning in the Renaissance, the biggest and most architecturally advanced town expansion project in Europe at the time.

In 1570 the city was held by Alfonso II d'Este, Duke of Ferrara, vassal of Pope Pius V, a beloved ruler and a devoted liberal art patron, but careless and a big spender as an administrator.

Even if he were walking on a thin line, Alfonso managed to avoid the Papacy's many diplomatic and legal challenges to the city independence, thanks to cunning politics and a strong friendship with the powerful Charles IX of France.

Alfonso was not new to compromises: to smooth his frequent brushes with the Pope, he was usually attending masses and acting as a good Catholic in public, receiving communion, giving substantial sums to charity, arranging religious parades for saints and building convents.

[2] Both the high taxation, and the soft stance with the Jews ultimately gained him hostility in the most die-hard Catholic part of the population, which supported an acquisition of the city and its lands by the Holy Seat.

Flames were reported to come out from the soil and raise into the air, probably small pockets of natural gas set free by cracks in the earth crust.

[5] Observers reported that the shallow bowl-shaped valley where Ferrara lies seemed to rise into a kind of hump, before coming back to its original profile.

Other than the facade, the Duomo lost the Corpus Domini chapel and part of a side wing: the heavy iron chain above the main altar fell to the ground, along with the columns' fine marble capitals.

The resulting situation, in which societal rules were upset or fell in disuse, was perceived as awkward and unnatural by both peasants and well-to-do, leading to common psychological issues amongst the population.

This unusual improvisation was not well regarded by the Pope and was seen as demeaning by other rulers, but ultimately it proved to be a wise choice and a necessity in view of the duration of the aftershocks.

The friars took some decomposing corpses from the rubble, and brought them in procession claiming that God was going to sink the city to hell if the people refused to drive Alfonso away.

The Duke made every effort to have the Castello Estense repaired in record time, to downplay his hardnesses with the other Italian rulers and to begin to restore a sense of normality in the evacuees.

After Castello Estense was made safe again, thanks to many iron rods and anchors, in March 1571 the Duke triumphantly relocated back to the city and the return to normality begun to look possible.

[5] Alfonso called on his court scholars in physics, philosophers and many "experts in various accidents" to inquire into the causes of the disaster, appointing as their leader the renowned Neapolitan architect Pirro Ligorio (a successor of Michelangelo as head of the San Pietro in Vaticano workshop), effectively founding the first seismological observatory and think tank on earthquakes in the world.

The essays were essential in disproving emerging theories that blamed the earthquake on the drainage of the many Duchy's swamps and their reclamation as fertile agricultural lands.

Pirro Ligorio was a scientist and a devout catholic: he needed to carefully weigh his words to avoid a clash with the Curia while at the same time proving that the Pope's claims were unfounded.

He kept a diary of the aftershock, writing in abundance of detail about their intensity and the damage they kept doing to the city, dramatically improving knowledge of shocks dynamics and consequences of an earthquake.

[7] Many of the empirical findings of Ligorio are consistent with contemporary anti-seismic practices: among them the correct dimensioning of main walls, use of better and stronger bricks as well as elastic structural joints and iron rods.

After the earthquake, many nobles and well-off merchants left the city, managing their business in their country villas or moving their houses to nearby towns.

Without the Jews' businesses, crushed by costly reconstruction debts and losing its thriving cultural circle, the city became a minor trade and agricultural hub up until the 19th century.

The annexation of Ferrara and Comacchio was disputed by many contemporaries, including the weak Duke of Modena Cesare d'Este who was the direct candidate to the succession, but was ultimately completed.