1583 Assembly of Notables

In the Grand Ordonnance de Blois issued in 1579, which summarised many of the requests of the Estates General, a large number of financial reforms were put forward.

However, Henri was forced to turn to various expedients due to the financial demands of first the civil wars, then his brother the duc d'Alençon's military exploits in Nederland and then the needs to pay off the foreign mercenaries to whom the crown was indebted.

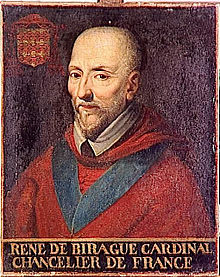

The Assembly of Notables opened in November 1583 and contained 66 participants, largely embodying administrative experts and functionaries, but also many of the great nobles of the kingdom such as the cardinal de Bourbon.

[2] The provinces baulked at the fiscal demands of the crown in 1578–1579, with the provincial Estates of Bourgogne, Bretagne and Normandie refusing to yield despite the sending of royal commissioners.

[11] In July 1582 Henri renewed the French alliance with some of the Swiss cantons and made a treaty with them at Solothurn concerning the arrears of their pay as mercenaries that cost the crown 600,000 écus.

[12] These expenses forced him to once more turn to expedients and he alienated more of the royal domain, created more venal offices, took out 6 new loans and instituted further taxes on the clergy, cloth and wine.

During a meeting of the conseil d'État on 16 July, Henri announced his intention that an investigation would be undertaken towards the dual purpose of the domain's redemption and the relief of the people's sufferings.

[16][12] Each area was to be overseen by a commission of four and was led by a prelate, and contained a member of the conseil privé (privy council) who had experience of war, a magistrate and an expert in finance.

[17] The Lyonnais, Dauphiné and Provence were entrusted to the bishop of Nantes, the seigneur d'Abain, Jacques Baillet an advisor to the grand conseil and Charles Le Comte one of the maître des comptes (master of accounts).

[18] Languedoc and Guyenne were the responsibility of the archbishop of Vienne, the sieur de Maintenon, Jean Forget a conseiller in the Paris Parlement and Denis Barthélemey one of the maìtre des comptes.

[22] By the Autumn of 1583, Henri's sécretaire d'État (secretary of state) the seigneur de Villeroy was growing concerned that France was faced with an increasingly urgent crisis of both internal and external dangers.

[43] Henri had hoped his brother Alençon would join him for the Assembly, and sent a request to this effect through the dispatch of his mother Catherine to La Fère to meet with the prince in August.

Catherine informed her son that Henri was hoping that both he and the baron de Biron would be present for the upcoming Assembly of Notables, so that they might explain the situation in Nederland.

[51] There would also be a 'Monsieur Marcel'; in addition to Beaurains and Baillet who had served in the commissions of 1582[53] Having been delayed by the plague, Alençon and the delegates from the provincial Estates, the assembly would open on 18 November 1583.

He discussed the state of justice in the kingdom harshly, critiquing what he considered to be anachronistic privileges such as the practice of the archbishop of Rouen to release a criminal of his choice.

[59] From 26 November to 8 December président Fauchet and général Roland were brought in from the cour des monnaies (sovereign court in charge of the coinage) to provide further direction to the delegates on financial matters.

[66] The punishment for fraudsters would be established in April 1584 at the value of five years of the tax, with the examination concerning itself with the records of 1583 out of suspicion that the guilty parties might try to reform their ways with the investigation arriving in 1584.

The prince had apparently been convinced by 'malicious' members of his entourage, that Henri intended to withdraw from Alençon his prerogatives over his appanage as a way of recovering the royal domain.

[72] To resolve looking improper in trials concerning the tax farms, Nevers proposed that instead of such cases being evoked to the conseil d'État that they rather remain in the ordinary courts.

Henri defined lèse majesté as the following crimes and more: a crime against the king and his authority; the unauthorised raising of soldiers, munitions and funds; the production of counterfeit currency; the fortification of private houses; exporting from France without permission gold, silver, wheat or wine; royal officials or prelates leaving the kingdom without Henri's permission and finally common people becoming pensioners of foreign powers.

Therefore they proposed Henri reserve strict enforcement of the lèse majesté law for those crimes that were more serious, attacks on the king and his authority, the raising of troops and moneys, and the production of counterfeit currency.

[76][26][77] As concerned the aides (excise taxes) the notables did not council removing the exemptions that Parisians enjoyed from them, but rather proposed introducing a limit on the amount of wine they were allowed to sell.

[77] Tax farmers had attempted to limit the publicity of the auctions and prey on the crowns financial embarrassment to secure the acceptance of lowest price for the farm.

[79] There were specific recommendations from the notables as regarded the grand parti du sel, a farm of salt which covered the areas around Paris, Rouen, Tours, Bourges, Orléans, Amiens, Dijon, Caen and the comté de Blois, a reexamation of the terms of the lease would be required.

[62] As concerned the maintenance of order in the kingdom at large, Henri wished to examine the roles of the various officials whose responsibility it was: the gouverneurs, lieutenants-généraux, baillis, sénéchaux and the prévôts des maréchaux (governors, lieutenant-generals, baillifs, seneschals and provost marshals).

[100] The money advanced to the king by Brouart as a result of this allowed Henri to pay his officers incomes, service the royal annuities and settle some of the crowns debts.

Henri wanted to put it out to a new bidder and if none could afford the entirety of the farm, to break it down into smaller pieces, however he was strongly resisted in this by members of his conseil and high finance.

The chambre des comptes of Provence sent a report on the principauté d'Orange to the royal conseil by which they argued that the French king enjoyed sovereignty over the small domain.

[94] Of course, the state's overall deficit remained vast, and the redemption of the royal domain incomplete, but if several years of internal peace would follow, it offered the possibility of success.

[106] During the Seventeenth and Eighteenth centuries, the conclusions of the 1583 Assembly of Notables were viewed as an impressive feat, which had only been sabotaged from delivering the benefits it was supposed to by the political circumstances of the time.