Electoral Franchise Act

The act was in force from 1885, when it was passed by John A. Macdonald's Conservative majority; to 1898, when Wilfrid Laurier's Liberals repealed it.

Four years earlier, in 1881, Parliament had enacted the Naturalization and Aliens Act, 1881, which, among other provisions, explicitly provided that Indigenous people did not count as full British subjects unless they were able to vote.

[5] The text initially would have allowed "spinsters" and widows who met property qualifications, as well as all Indigenous people who owned land with at least $150 in capital investment, to vote.

[15] These statutes also mandated that Indigenous people be fluent in English or French, have "good moral character", be educated, and lack debt, if they desired to become citizens.

[27] Amendments from the original text of the bill restricted the franchise considerably, preventing all women,[5] most Indigenous people west of Ontario,[5] and those of "Mongolian or Chinese race"[6][28] from voting.

[31] In a shift from previous federal legislation, the Electoral Franchise Act did not Indigenous people to surrender Indian status in order to vote.

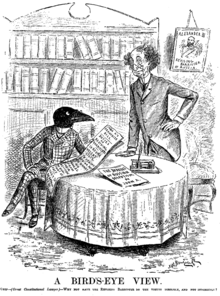

[33][34][35] Gordon Stewart argues that the legislation was of "basic importance" to Macdonald and his party because electoral margins at the time were routinely razor-thin and thus control over lists of those qualified to vote was vital in winning elections.