1905 Alberta general election

[2][3] After the Deed of Surrender was enacted, the United Kingdom transferred ownership of Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory from the Hudson's Bay Company to the government of Canada.

[11] The federal government heeded the calls of the settlers and expanded the borders of Manitoba westward on July 1, 1881, encompassing much of the densely populated areas of the Territories.

[17] However, Brett's proposal failed to garner support and was opposed by Premier Haultain who preferred the Territories form a single large province.

[17] Wilfrid Laurier's government was not prepared to consider the proposals, due to concerns about difficult questions surrounding religious education, the delegation of authority, and general apathy towards provincehood of western liberal members of parliament such as Frank Oliver.

[18] The Territories were under growing financial stress from limited revenue generation authorities while there was wave of immigration and population growth and rising demands for improved government infrastructure and services.

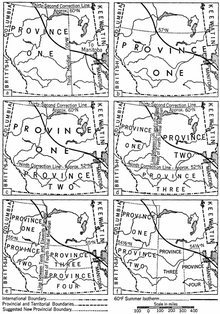

[22][23] When the Autonomy Act was passed, it split the North-West Territories along the 4th meridian of the Dominion Land Survey creating two provinces of roughly equal area of 275,000 square miles (710,000 km2) and 250,000 people.

[24][25] The federal government under Laurier believed that one single province would be too large to effectively manage, and the territory above the 60th parallel north was unfit for agriculture, and therefore had little hope of "thick and permanent settlement".

[30][32] Instead, the main issue with provincehood in the North-West Territories was the debate over the location of the new provincial capital and whether the federal government or the new provinces would have ownership of public lands and resources.

[30] The bill retained federal control over public lands and natural resources, and the provinces were promised $375,000 annually each with a provision for population growth.

[40][41] According to historian Lewis Thomas, Laurier's decision to remain silent on naming a Premier helped weaken Haultain's position as the heir apparent in Alberta.

[42] Laurier's appointment of staunch Liberals in Bulyea, Forget, Rutherford and Walter Scott ushered in party politics to the new prairie provinces.

[48] However, the town's small size and lack of interest from federal officials made it difficult for Red Deer to be considered a serious contender.

[49] After the election resulted in an overwhelming Liberal majority, Premier Rutherford announced the location of the capital city was to be chosen by an open vote of the Legislature.

[50] Calgary's newspapers and its Board of Trade, recognizing the uphill battle of their city to be named capital, made little effort to rally Calgarians and southern Albertans to the cause.

[53] The choice of Edmonton was supported by three Liberal MLAs of southern Alberta - Simpson (Innisfail), Marcellus (Pincher Creek) and Finlay (Medicine Hat).

[54] After bitter debate across Canada, the proposed Alberta Act was amended by Laurier in second reading on March 22[55] and later passed by the 10th Canadian Parliament with provisions providing minority faiths with the right to separate schools under provincial control.

[64] Calgary and southern Alberta's conservative-leaning was linked to the presence of the Canadian Pacific Railway which was generally regarded as exercising influence on behalf of the conservative movement.

[65] The party did not take an official stance on the issue of separate schools for minority faiths being included in the Alberta Act, owing to the influence of Bennett and Senator James Lougheed.

[56] However, Bennett made a speech criticizing the federal government for including the separate school provisions in the Alberta Act, describing it as an attack on provincial rights.

[62] Historian Lewis Thomas notes that the Liberal strategy to connect Bennett to the Canadian Pacific Railway was successful, as many Albertans resented the corporation for various reasons.

This included a story accusing Calgary Conservative organizer William L. Walsh of attempting to bribe Daniel Maloney to run as a candidate in the St. Albert constituency.

Historian Lewis Thomas notes the final layout favoured northern Alberta with one additional district, despite Oliver and Talbot being aware that more than 1,000 more voters south of the Red Deer River participated in the 1904 Territorial election.

[35][78] If a scrutineer disputed a voter's eligibility, the individual would be required to complete a form providing their information and place it in an envelope with their ballot.

The scandal led to the arrest of some key Liberal organizers, including William Henry Cushing's campaign manager, who had been a returning officer at a Calgary polling station.

Dubec received the greater number of votes, but Rutherford's Cabinet overturned the election results in mid-January due to significant irregularities, leaving the seat vacant.

An appeal was launched into the legality of Cabinet deciding on the legitimacy of an election, which was upheld when Judge David Lynch Scott found the court had no jurisdiction to consider the case unless delegated by the legislature.

Lucien Dubuc, the conservative runner-up candidate from the original 1905 election, did not run again, resulting in a rare two-way race under the same party banner.

[89] Some Conservatives also attributed the loss to non-Anglo-Saxon voters,[86] but the victories of Cornelius Hiebert in Rosebud and Albert Robertson in High River went against this trend.

Hiebert, a Russian-born Mennonite, won in his constituency, while Robertson was aided by a third candidate siphoning votes from the incumbent Liberal opponent.

[90] Furthermore, Thomas argues that the strong positions taken by the Conservative Party on the provincial right to control the school system and public lands did not make a significant impression on voters.