1916 Australian conscription referendum

It was the first non-binding Australian referendum (often referred to as a plebiscite because it did not involve a constitutional question), and contained one proposition, which was Prime Minister Billy Hughes' proposal to allow conscripted troops to serve overseas during World War I.

Due to the controversial nature of the measure, and a lack of clear parliamentary support, Hughes took the issue to a public vote to obtain symbolic, rather than legal, sanction for the move.

He had long supported compulsory military service even before Australia's Federation,[2] and his affection and camaraderie with troops would eventually earn him the moniker "The Little Digger".

However, despite some calls from leading politicians, the issue was divisive within Hughes' Labor Party, and he hoped conscription could be avoided through sufficient volunteerism.

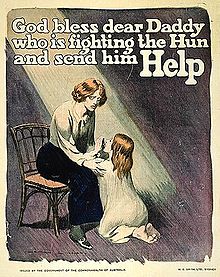

A mass campaign to mobilise new recruits was started in November 1915, and proved to be successful over the next six months at sustaining a steady flow of new troops to the front.

Hughes had left for Great Britain (where conscription had just been introduced) in January 1916 to take part in the planning of the Allied war effort.

Whilst abroad he went on extended tours on the front lines, and formed a strong personal bond with the soldiers that he visited, particularly those recovering in English and French hospitals.

Hughes received word from Deputy Prime Minister George Pearce that troop replacements would be insufficient by December 1916 even at the most generous estimates.

[5][6] In late August, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies cabled the Australian government notifying it of the heavy losses in France and warning that as many as 69,500 reinforcements would be needed within the next three months to keep the AIF 3rd Division in service.

[7] The cable was initially spurred by Hughes' own Australian representative in the British War Cabinet, Brigadier General Robert Anderson, keen to assist in the conscription campaign, working in concert with Bonar Law and Keith Murdoch.

Although Hughes was eager for conscription to be enacted immediately after returning from England, he bided his time in July and August to politically organise before putting the motion before Parliament.

It became clear that support for a bill to introduce compulsory overseas conscription would be passed in the House, with the Opposition making up the deficit from Labor defectors, but not in the Senate.

The Governor-General, Ronald Munro Ferguson, 1st Viscount Novar, was a stern imperialist who openly associated with the David Lloyd George government in England and was influential behind the scenes in pushing for conscription to aid the Empire's war effort.

Realising the impasse, Munro Ferguson promised Hughes upon his return that he would sign a bill for conscription, and grant a double dissolution if the parliament could not pass it.

He pulled out all the stops in the advocacy of his proposal, claiming that France was on the verge of collapse, Imperial forces were stretched to the limit, and Germany was winning the war just about everywhere.

In September, Opposition and Commonwealth Liberal Party leader Joseph Cook addressed parliament in support of conscription: "There are some that do not believe in the compulsion of men, who say that Australia has done enough ...

A group of 15 representatives and 12 senators, led by Frank Brennan and Myles Ferricks, opposed the bill at every stage on the grounds that it was a question of conscience on which no majority, no matter how large, had a right to impose its will on the minority.

The Age published an analysis of the situation on 13 April and came to the conclusion that "if a vote were taken of the rank and file of the entire movement, there would be an undoubted demand for conscription".

The issue never got off the ground in a coherent way, and many counter-argued that taxation was exactly a form of wealth conscription, and that fixed assets could hardly be mobilised with sufficient liquidity to help the war effort.

Frank Anstey proclaimed on the floor of parliament during the introduction of the bill: "The clause provides that this measure may be cited as 'Military Service Referendum act', and I am of the opinion that its objects and purpose should be stated in more explicit language in that title.

[29] Anti-conscriptionists, especially in Melbourne, were also able to mobilise large crowds with a meeting filling the Exhibition Building on 20 September 1916;[30] 30,000 people on the Yarra bank on Sunday, 15 October,[31] and 25,000 the following week;[32] a "parade of women promoted by the United Women's No-Conscription Committee – an immense crowd of about 60,000 people gathered at Swanston St between Guild Hall and Princes Bridge, and for upwards of an hour the street was a surging area of humanity".

[33] An anti-conscription stop work meeting called by five trade unions held on the Yarra Bank mid-week on 4 October attracted 15,000 people.

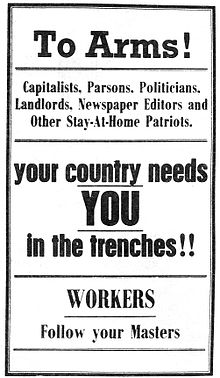

The numerous anti-conscription meetings went largely unreported, and Hughes had little opportunity to address the Labor and working class audiences which he had traditionally identified with.

[36] Anticipating that the referendum would pass, and desiring that as many men as possible be readied for service following its passage, Hughes issued a directive that severely undermined his popularity.

Using pre-existing powers under the Defence Act, Hughes ordered all eligible men between 21 and 35 to report for military duty, to be examined for medical fitness, and then go into training camp.

Hughes, distraught and overwrought, called the Governor-General at midnight, saying he had no one else to talk to, and the two men conversed in the wee-hours of the morning, with Lord Novar offering sympathy and support to his old colleague, but ultimately both understood that the cause was probably lost.

The Labor movement, and the 'anti' cause in general, had fought under many disadvantages, and the 'yes' campaign had most of the media, many major public institutions, and many of the state governments on its side.

The heavy-handed tactics, the arrogance displayed, and eventually the dirty fighting, created more detractors than supporters; these faults, and additionally Hughes' inability to appeal, either directly or indirectly, to many ordinary voters, were major problems that hampered the 'yes' campaign.

Recruitment was temporarily helped by the small surge caused by the general call-up just before the vote (enough at least to maintain the lower estimates of troop needs for a few months).

Despite the numerous political post-mortems and attempts at reconciliation, it was now clear to most people that Hughes could no longer command the respect or service of his Labor Party colleagues.