1927 Chicago mayoral election

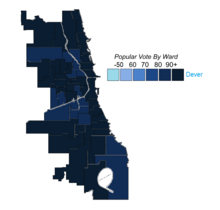

To receive the Democratic nomination, Dever won the party's primary election with 91 percent of the vote, facing only a single weak opponent.

[1] Observing the corruption of city government caused by bootleggers, he resolved to crack down on the illegal liquor trade and strengthen enforcement of Prohibition.

[3] Nevertheless, the limited supply of alcohol led to bootleggers competing with one another, increasing violence in the city,[3] lowering Chicagoans' approval of Dever's performance.

[4] Aware of the effects of Prohibition enforcement on his mayoralty, Dever was reluctant to run for a second term in 1927, a feeling strengthened by poor health and lucrative job offers in the private sector.

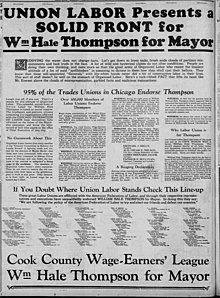

[10] He was immensely popular with the city's African-American community,[11] having served as alderman of the 2nd ward, home of Chicago's largest black population,[12] from 1900 to 1902.

[18] Serving at the time as President of the West Parks Board,[b][20] he promised to enforce Prohibition while it was still on the books and to smash organized crime in thirty days if elected, comparing gunmen gangs to boils and the bootleg industry to an appendix.

The New York Times characterized the primaries as plagued by, "shootings, sluggings, theft of ballot boxes, police raids and the arrest of about two hundred gangesters and repeaters at the polls".

[28][30] Attorney Martin Walsh of the 27th ward filed on February 2, claiming to have the backing of "the old municipal ownership leaders" and joining the race "to give Mayor Dever a little exercise.

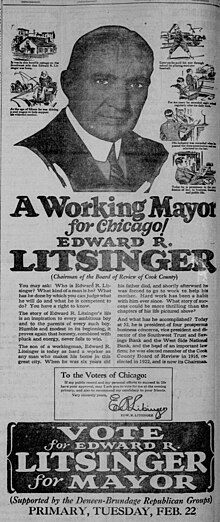

Senator Charles S. Deneen and Edward J. Brundage,[20][34] (the latter of whom had split from his political ally Robert E. Crowe by supporting Litsinger[35]), announced his platform on January 9.

[34] He promised to compel the City Council to adopt an ordinance that would end the Chicago Traction Wars and consolidate all transportation lines under public ownership,[c] to construct subways, to form a police investigation into the rampant crime, to look at causes of recent tax increases and investigate potential ways to reverse them, and to clean up streets and alleys.

[20][38] Former policeman Eugene McCaffrey filed for candidacy on February 2 and attracted suspicion as many of the names on his petition sheets appeared to have been written in the same handwriting.

[39] Thompson accused Robertson of messy eating, stating that "[With] eggs in his whiskers, soup on his vest, you'd think the doc got his education driving a garbage wagon.

[39] In an open letter, Thompson charged that Edward Brundage and Fred Lundin were suburbanites and were guilty of betraying their city roots.

[46] Thompson declared that his America First slate would elect so many of its candidates that "the king of England will find out for the first time he is damned unpopular",[8] and implied that he might have Dever sent to jail.

[55] He attempted, particularly early in the race, to tout parts of his record such as his construction of Wacker Drive and 51 new schools, as well as a pure milk ordinance he had helped pass.

[63] At a rally on March 28, 1927, Robertson announced that, if elected, he would appoint former United States attorney Edwin A. Olson as police chief.

Other crime figures backing Thompson included Jack Zuta,[77] who gave $50,000[h] to his campaign,[78] Timothy D. Murphy, and Vincent Drucci.

[80] He was backed by businessmen Sewell Avery, Julius Rosenwald, and W. A. Wieboldt,[55] as well as university presidents Max Mason and Walter Dill Scott and attorney Orville James Taylor.

[55] He was also backed by socialites Louise deKoven Bowen and Edward Ryerson Jr, as well as builder Potter Palmer and Donald Richberg.

[51] In addition to Lundin,[81] Robertson was supported by the incumbent[i] 43rd ward alderman Arthur F. Albert,[83] whose opponent Titus Haffa endorsed Thompson.

[71] Despite Thompson's popularity with African American voters, there were Edward Herbert Wright-aligned Black Republicans who publicly backed Robertson.

[91] Newspaper advertisements for Robertson's campaign run by the Chicago Business Men's Republican Committee included straw polls which each surveyed several locations in the city.

[107] Ultimately, the Chicago Police Department sent 5,000 men (including standard policemen, plain clothes officers, and special machine gun squads) to guard the polls.

[81][73] The Sherman House Hotel, home to both Dever and Thompson's campaign headquarters, was given police security scrutiny on election day.

Two buildings were bombed, including a soft drink establishment owned by State Representative Lawrence C. O'Brien[110] and the 42nd ward Democratic Party headquarters.

"[aa][50][125] The St. Louis Star declared that "Chicago is still a good deal of a Wild West town, where a soapbox showman extracting white rabbits from a gentleman's plug hat still gets a better hearing than a man in a sober suit talking business.

[130] George Schottenhamel, writing in 1952 for the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, argued that Dever "would have been easy opposition for any candidate" running "on a campaign of 'Dever and Decency' despite four years of rampant crime in Chicago".

[136] Koop's performance of two votes was picked up by the Associated Press[137] and used by an editorial of the Ottawa Citizen as evidence that the threat of socialism was overblown.

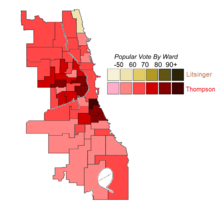

[140][141] Thompson would lose to Democrat Anton Cermak in the 1931 Chicago mayoral election[142] as his public approval fell victim to continuing crime and the Great Depression.

[143] Historians generally consider Thompson one of the most unethical mayors in American history, in large part due to his alliance with Capone.