1930 24 Hours of Le Mans

When that car was put into the sandbank at Pontlieue corner, it was the other works Bentley of Woolf Barnato and Glen Kidston taking up the Germans’ challenge.

The Bugatti of Marguerite Mareuse and Odette Siko had a trouble-free run and finished seventh, stealing the contemporary headlines from Bentley.

The biggest change this year was the Automobile Club de l'Ouest (ACO) now allowing private entrants as well as “works” entries from the manufacturers.

Many small companies were selling bare chassis upon which an owner would get a coach-builder to put on a body-shelled, so the specifications were still quite broad as long as the car had some basic minimum equipment (mudguards, lights, hood, windscreen etc.).

Example targets included the following:[3] The Société des Pétroles Jupiter, Shell's French agents, provided three standard fuel options: Gasoline, Benzole and a 70/30 blend of the two.

[4] Defending champions Bentley once again arrived with a solid works team, this year bringing a trio of their big Speed Six model.

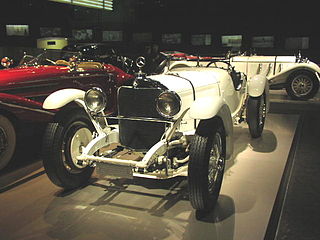

[5] Back in 1928, Barnato's fellow race-winner, Sir Henry “Tim” Birkin had seen the threat posed by the new supercharged Mercedes and Alfa Romeos to Bentley's dominance of touring car racing.

[6] He eventually found an investor in the form of young heiress, and keen motorist, Dorothy Paget (who already owned a Mercedes-Benz SSK).

The cars were not race-ready in time for the 1929 race; however Barnato quietly approved sufficient funds to allow the required production quantity to be met.

[6] Birkin renewed his 1928 Le Mans partnership with Jean Chassagne, while race-winner Dudley Benjafield drove with former Alfa Romeo test-driver (and now British resident) Giulio Ramponi.

Keen to keep his anonymity he raced under the pseudonym “Georges Philippe” and had an American banking friend, Dick Parke, put the entry in for him.

Georges Roesch, chief engineer at Clément-Talbot, was concerned that like the Blower Bentleys, the French fuels would not be suitable for the Talbots.

Leslie Callingham, head of Shell's technical department in London (and driving an Alfa Romeo in the race) said the hybrid fuel would be suitable, although the engine output would drop to about 70 bhp.

Vittorio Jano’s 6C successor design, debuting in 1927, followed on this adapting as a sports car or grand prix racer in the Formula Libre events.

However, a car owned by wealthy British racer Earl Francis Howe was entered, with support from the Stiles team including former Bentley driver, Leslie Callingham as co-driver.

[11] After the withdrawals of Alvis and the new Scotsman car, the only entries in the 2-litre class were from BNC and Kenneth Peacock's supercharged Lea-Francis S-Type.

[12] BNC had not survived the economic downturn and had been purchased by French entrepreneur Charles de Ricou, who also picked up Lombard and Rolland-Pilain, and its successor AER.

[14] Jean-Albert Grégoire’s small Tracta company had been very successful at Le Mans with its reliable front-wheel drive and patented Universal joint system.

The team decided to switch to the pure-benzol option, but it meant changing the engine compression ratios and fitting new pistons.

[21] The other Stutz had also had problems, with Brisson handling a misfiring engine at the start and then Rigal running off the road a couple of times, dislodging the exhaust pipe.

[23] They picked up a place as the Alfa Romeo was delayed – a race-long struggle with fouled plugs and ignition from the blended fuel.

[11] At the back of the field, the nimble MGs were easily leading the Tractas (delayed, like others, by plug issues[15]) in their own battle for small-engine honours.

[19] Mercedes team manager Neubauer authorised his driver to start re-using the supercharger to close back in and going into the night, the spectators watched a thrilling duel as the two cars swapped the lead.

With two hours to go, Eaton pitted his Talbot to clear a fuel blockage: a paper label off a fuel-churn had fallen in and got stuck on the filter.

The handicapping favoured the smaller car and Eaton's hard driving soon retook the lead only to lose it again when they pitted to free a stuck throttle.

[12] In a tight finish, Talbot won the Index prize by the narrowest of margins: only 0.004 from the winning Bentley, amounting to barely a lap between them.

But like many other manufacturers, the company was hit hard with plummeting demand in the Great Depression and soon after Bentley disbanded its works racing team.

A keen pilot, he was attempting an endurance record from England to Cape Town when he was killed on the return route when his plane broke up pin stormy weather.

[22] In October, Dorothy Paget withdrew her financial support for the Blower Bentley project after ongoing unreliability and only limited success.

[19] Philippe de Rothschild, knowing his identity was now revealed, retired from racing to build his family company into one of the great French wine labels.