1931 United Kingdom general election

MacDonald subsequently campaigned for a "Doctor's Mandate" to do whatever was necessary to fix the economy, running as the leader of a new party called National Labour within the coalition.

Disagreement over whether to join the new government also resulted in the Liberal Party splitting into three separate factions, including one led by former Prime Minister David Lloyd George.

Crucially, Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Snowden refused to consider deficit spending or tariffs as alternative solutions, and without any other options to address the crisis the government was forced to resign.

While initially against an early election, MacDonald came to endorse the idea in order to take advantage of Labour's unpopularity due to its poor economic record in office.

While this was happening, former prime minister David Lloyd George was still technically the Liberal Party's leader—however, due to having undergone an operation in early 1931, with a long recuperation, he was unable to take up a ministerial role when the National Government was formed.

[4] In order to appease the various factions within the coalition its manifesto avoided proposing any specific policy, and instead asked voters for a "Doctor's Mandate" to do whatever was necessary to rescue the economy.

[5] An additional problem for Labour came from the 2.5 million Irish Catholics in England and Scotland, who had traditionally been a major component of their working class base.

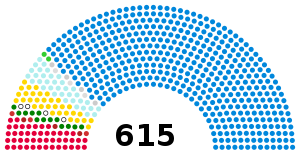

The victory gave the National Government a clear mandate to enact its policy platform, which the coalition believed would pull the economy out of the doldrums of the Great Depression.

MacDonald remained Prime Minister, but the Conservatives were the dominant party within the coalition—National Labour contested only 20 seats, winning 13—and with his increasingly poor health over the course of the parliament he came to be more of a figurehead for the government rather than an active leader.