1934 24 Hours of Le Mans

By the halfway point, there was only a single competitive big-engine car left running, and interest shifted to the race for the Index of Performance between the four British firms of Aston Martin, MG, Riley and Singer.

Made of concrete with capacity for 60 cars, it was separated from the pit lane and racing track by a wooden picket fence.

Eco and Jupiter, the French distributors of Esso and Shell fuel respectively, pay for each pit-box to be installed with a 1000-litre tank, gantry and hoses to allow refuelling direct to the cars.

With the new fuel rigs, the ACO allowed a second mechanic to work on a car in the pits, nominated solely as the refueller.

[5] The ACO made significant increases to the class distance-targets, this time in the mid-range engines, with an extra 125 km added to the minimum distance for 3-litre cars for example.

[7] Out of the 52 applicants, 45 arrived on race-week for scrutineering with works entries received from the British Aston Martin, Riley and Singer companies and the small French manufacturer Tracta.

From the thirteen finishers in the previous year’s race, twelve returned to contest the Biennial Cup, which therefore shaped up to be a significant competition.

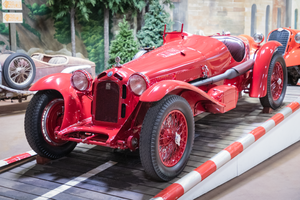

[9] Chinetti had a corto (short-wheelbase) Mille Miglia chassis and brought in French Grand Prix racer Philippe Étancelin as his co-driver.

He returned this year with his 8C-2300 Le Mans, with its 4-seater lungo (long) touring body and with former Talbot stalwart Tim Rose-Richards as his co-driver.

Racing journalist Roger Labric got a degree of works support, with two mechanics from Molsheim and driver Pierre Veyron.

There were also three Imps, including a private effort sponsored by Dorothy Champney (who would soon marry managing director Victor Riley), who had Kay Petre as her co-driver.

[16] The MG K3 had proven to be a giant-killer in British handicap races and on the continent, including consecutive Tourist Trophy victories by Tazio Nuvolari.

His drivers were Brian Lewis, Baron Essendon (fresh from winning the Mannin Moar on the Isle of Man) and Johnny Hindmarsh.

The most interesting variant was that of Jean de Gavardie, along with the straight-6 1092cc engine without its supercharger (which meant needing 13 fewer laps to be run), was fitted with a streamlined aluminium "tank" bodyshell.

Two works entries (for Stan Barnes’ brother Donald with journalist Tommy Wisdom, and Norman Black/Roddy Black)were supported by two other privateer efforts.

Alfa Romeos filled the top four places with Sommer, Rose-Richards, Chinetti and Saunders-Davies ahead of Veyron and Brunet in their Bugattis.

[30][10] Over the course of the next two hours, Howe drove hard to get back up to sixth place until at 1am he pitted with clutch problems that proved to be terminal.

[30][11] This all allowed the remarkable progress of the 1.1-litre MG to continue, with Ford and Baumer now up to second, ahead of the Brunet Bugatti Type 55.

The Biennial Cup was being dominated by the small British cars, with the von der Becke/Peacock Riley leading the MG, with the Fothringham/Appleton Aston Martin in third, and fourth on the track.

Following the MG, Charles Brunet was blinded by the headlights facing towards him and his Bugatti ended up parked beside the MG. Anne-Cécile Rose-Itier narrowly avoided the carnage.

Although with a 100-km lead, their leaking fuel-tank gave the pursuing pack of small British cars hopes of an improbable victory.

The Morris-Goodall Aston Martin was now second with the three Rileys of van der Becke (still leading the Biennial Cup), Sébilleau and Dixon next; the team having an excellent race.

Gordon Hendy’s privateer Singer had been delayed by fuel-feed issues[31] and the gearbox of the Bertelli Aston Martin had finally packed up and taken too long to repair.

Then, after running second for almost eight hours, the engine of Morris-Goodall’s Aston Martin suffered a broken oil pipe stranding him out on the track.

[36] Chinetti and Étancelin took the flag with a large margin of 13 laps 180 km (110 mi) – the biggest of the decade, and second only to the Bentley win in 1927.

In contrast, having been without direct competition for over half the race, the gentler pace of the winners as they eased off meant it was the shortest distance covered in the decade.

The 1.1-litre car of Peacock/van der Becke, coming home in fifth, repeated their victory in the Index of Performance from the year before, completing an outstanding 52 laps (37%) over target.

Delayed early on for 45 minutes with carburettor problems, they had driven very hard through the night and all Sunday back up the field, making up time.

[19] Étancelin was honoured with a civic reception in his home city of Rouen and he resolved to drive the winning Alfa Romeo to the event.

The car was filled with petrol for the journey, but by the time he brought his bags down from the hotel, the gas had leaked out all over the forecourt, as the fuel tank had not been repaired since the finish.