Palestinian expulsion from Lydda and Ramle

In July 1948, during the 1948 Palestine war, the Palestinian towns of Lydda (also known as Lod) and Ramle were captured by the Israeli Defense Forces and their residents (totalling 50,000–70,000 people)[2][3] were violently expelled.

[7] The exodus, constituting the biggest expulsion of the war,[8] took place at the end of a truce period, when fighting resumed, prompting Israel to try to improve its control over the Jerusalem road and its coastal route which were under pressure from the Jordanian Arab Legion, Egyptian and Palestinian forces.

Using a column of jeeps led by a Marmon-Herrington Armoured Car with a cannon—taken from the Arab Legion the day before—he launched the attack in daylight,[32] driving through the town from east to west machine-gunning anything that moved, according to Morris, then along the Lydda-Ramle road firing at militia posts until they reached the train station in Ramle.

According to a contemporaneous IDF account: "Groups of old and young, women and children streamed down the streets in a great display of submissiveness, bearing white flags, and entered of their own free will the detention compounds we arranged in the mosque and church—Muslims and Christians separately."

[53] Benny Morris writes that David Ben-Gurion and the IDF were largely left to their own devices to decide how Palestinian Arab residents were to be treated, without the involvement of the Cabinet and other ministers.

[54] As the shooting in Lydda continued, a meeting was held on 12 July at Operation Dani headquarters between Ben-Gurion, Yigael Yadin and Zvi Ayalon, generals in the IDF, and Yisrael Galili, formerly of the Haganah, the pre-IDF army.

[64] By 13 July the townspeople had undergone aerial bombardment, ground invasion, had seen grenades thrown into their homes and hundreds of residents killed, had been living under a curfew, had been abandoned by the Arab Legion, and the able-bodied men had been rounded up.

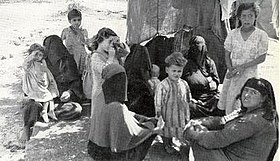

They walked six to seven kilometers to Beit Nabala, then 10–12 more to Barfiliya, along dusty roads in temperatures of 30–35 °C, carrying their children and portable possessions in carts pulled by animals or on their backs.

[72] Another IDF soldier described how possessions and people were slowly abandoned as the refugees grew tired or collapsed: "To begin with [jettisoning] utensils and furniture, and in the end, bodies of men, women, and children, scattered along the way.

[83] George Habash, one of the expelled who later founded the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, said that the Israelis took watches, jewellery, gold, and wallets from the refugees, and that he witnessed a neighbour of his shot and killed since he refused to be searched.

[95] Some of the refugees reached Amman, the Gaza Strip, Lebanon, and the Upper Galilee, and all over the area there were angry demonstrations against Abdullah and the Arab Legion for their failure to defend the cities.

[96] Alec Kirkbride, the British ambassador in Amman, described one protest in the city on 18 July: A couple of thousand Palestinian men swept up the hill toward the main [palace] entrance ... screaming abuse and demanding that the lost towns should be reconquered at once ...

[97]Benny Morris writes that, during a meeting in Amman on 12–13 July of the Political Committee of the Arab League, delegates—particularly from Syria and Iraq—accused Glubb of serving British, or even Jewish, interests, with his excuses about troop and ammunition shortages.

Perie-Gordon, Britain's acting minister in Amman, told the Foreign Office there was a suspicion that Glubb, on behalf of the British government, had lost Lydda and Ramle deliberately to ensure that Transjordan accept a truce.

[100] Bernadotte's mediation efforts—which resulted in a proposal to split Palestine between Israel and Jordan, and to hand Lydda and Ramle to King Abdullah—ended on 17 September 1948, when he was assassinated by four Israeli gunmen from Lehi, an extremist Zionist faction.

Once Israel was admitted to the UN, it retreated from the protocol it had signed, because it was completely satisfied with the status quo, and saw no need to make any concessions with regard to the refugees or on boundary questions.

[105] The immigrants were assigned Palestinian homes—in part because of the inevitable housing shortage, but also as a matter of policy to make it harder for former residents to reclaim them—and could buy refugees' furniture from the Custodian for Absentees' Property.

The military administrators did satisfy some of their needs, such as building a school, supplying medical aid, allocating them 50 dunams for growing vegetables, and renovating the interior of the Dahmash mosque, but it appears the refugees felt like prisoners; Palestinian train workers, for example, were subject to a curfew from evening until morning, with periodic searches to make sure they had no guns.

[109] One wrote an open letter in March 1949 to the Al Youm newspaper on behalf of 460 Muslim and Christian train workers: "Since the occupation, we continued to work and our salaries have still not been paid to this day.

[115] Father Oudeh Rantisi, a former mayor of Ramallah who was expelled from Lydda in 1948, visited his family's former home for the first time in 1967: As the bus drew up in front of the house, I saw a young boy playing in the yard.

"Me too," I said ...[116]Yitzhak Rabin, Allon's operations officer, who signed the Lydda expulsion order, became Chief of Staff of the IDF during the Six-Day War, and Israel's prime minister in 1974 and again in 1992.

[117] Khalil al-Wazir, the grocer's son expelled from Ramle, became one of the founders of Yasser Arafat's Fatah faction within the PLO, and specifically of its armed wing, Al-Assifa.

The PFLP was also behind the 1972 Lod Airport massacre, in which 27 people died, and the 1976 hijacking of an Air France flight to Entebbe, which famously led to the IDF's rescue of the hostages.

[121] Anita Shapira calls them "the Palmach generation": historians who had fought in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, and who thereafter went to work for the IDF's history branch, where they censored material other scholars had no access to.

For them, Shapira writes, the Holocaust and the Second World War—including the experience of Jewish weakness in the face of persecution—made the fight for land between the Arabs and Jews a matter of life and death, the 1948 war the "tragic and heroic climax of all that had preceded it," and Israeli victory an "act of historical justice.

[121] Arab historians published accounts, including Aref al-Aref's Al Nakba, 1947–1952 (1956–1960), Muhammad Nimr al-Khatib's Min Athar al-Nakba (1951), and several papers by Walid Khalidi.

[127] The positions of Karsh and Morris, though they disagree, contrast in turn with those of Ilan Pappé and Walid Khalidi, who argue not only that there were widespread expulsions, but also that they were not the result of ad hoc decisions.

Rather, they argue, the expulsions were part of a deliberate strategy, known as Plan Dalet and conceived before Israel's declaration of independence, to transfer the Arab population and seize their land—in Pappé's words, to ethnically cleanse the country.

[62] Whereas traditional historiography in Israel has insisted that Palestinian refugees left their lands under the orders of Arab leaders, some Israeli scholars have challenged this view in recent years.

[140] Let us sing then also about "delicate incidents" For which the true name, incidentally, is murder Let songs be composed about conversations with sympathetic interlocutors who with collusive chuckles make concessions and grant forgiveness.

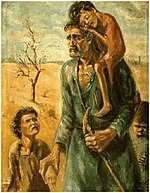

Where to ...? (1953)