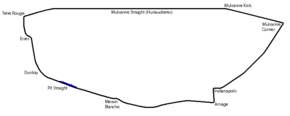

1949 24 Hours of Le Mans

During the war the RAF, then the Luftwaffe, had used the airfield by the pits, as well as the 5 km Hunaudières straight as a temporary airstrip (thereby also making it a target for Allied bombing).

Assisted with money from the government, the pits and grandstand had been rebuilt, a new 1000-seat restaurant and administration centre built and the whole track was resurfaced.

However, for this new start, sportscar prototypes were now given admission for the first time, "as an exceptional measure to contribute towards a faster revival of automobile manufacture" by the French Service des Mines (Vehicle registration authority), or its foreign equivalent[5] That was, in a sense, just formalising an unofficial practice started in the 1930s, when race-specific cars were entered at Le Mans and other races for the win with no intentions of going into full production.

[2] In days of petrol rationing, there was considerable interest in the Index of Performance - the measure of cars making an improvement on its nominal assigned distance, based on engine size.

Fuel, oil and water could only be topped up after 25 laps had been run, and ACO inspectors sealed the radiator and oil-caps after each refill.

These included 3 Talbots, 7 Delahayes, 4 Delages and a Delettrez, driven by its constructor brothers – the first diesel-engined car to compete at Le Mans, using an engine from an American Army GMC truck.

Most French hopes rested on the Delahayes: there were two new 4.5L 175 S raced by Parisian car-dealer Charles Pozzi (himself teamed with 1938 winner Eugène Chaboud), as well as five privately entered pre-war type 135 CS (a sports-car version of the 135 S grand prix car, and race-winner in 1938), running the smaller 3.6-litre 160 bhp engine.

Delage was represented by four D6S cars, all privately entered, built just after war's end in the Delahaye factory but based on a pre-war chassis and the old 3.0-litre, 145 bhp engine.

In retrospect, the biggest news was the arrival of an Italian newcomer: Enzo Ferrari was represented by two racing versions of his first production car, with a two-litre V12 developing 140 bhp and a top speed of 210 km/h.

Entered from Great Britain were a new Frazer-Nash ‘High-Speed’, driven by British motorcycle ace Norman Culpan, and company owner Harold Aldington and a works trio of lightened HRG 1500s (co-organised by future Gulf team manager John Wyer).

A number of small specialist sportscar companies started up in post-war France, and two of the most significant were those of Amédée Gordini, and Charles Deutsch/René Bonnet.

Under the ‘prototype’ provision, a half-dozen Simcas were entered with a variety of bodystyles and one of those (for Mahé/Crovetto ) was installed with the race's first pit/car radio, as pioneered in American motor-racing.

There was no grid based on practice time, instead the cars would be lined up, in echelon, in numerical order for the iconic “Le Mans start”.

At the end of the first hour, Chaboud and Flahaut led in the Delahayes, from Dreyfus, Rosier, Chinetti, and Vallée in one of the big Talbots.

[16] Yet barely half an hour later, just before dusk, Chaboud, with a big lead, stopped at Mulsanne with an engine fire, burning out the electrics.

Right up to the last lap he was pulling spectacular four-wheel drifts on the corners, thrilling the growing crowd sensing a heroic French victory.

At 4pm Charles Faroux, originator and director of the race since its inception in 1923, was again the man to wave the chequered flag – overseen by the new French President, Vincent Auriol.

[20] The big #1 Talbot-Lago SS sedan had been running well all race and had comfortably moved into 4th place until the very last lap when it stopped on circuit with engine failure (or out of fuel!).

Veterans Georges Grignard (who would later buy the stock of the bankrupt Talbot company[22]) and Robert Brunet brought home the first of the Delahayes, in 5th place winning the S5000 class.

Having had a night's sleep afterward, Hay then swapped the big fuel tank for the family luggage and they headed off to the Côte d’Azur on holiday.

[23] After the demise of the DB, it was the HRG of Jack Fairman (in his first Le Mans) who inherited the 1500cc class lead despite being 10 laps adrift and he held that to the end of the race.

Such overachievement also meant a clear victory in the Index of Performance, giving a clean sweep to Ferrari of all the silverware – a spectacular effort for a company competing in its very first Le Mans, not matched until McLaren’s comprehensive win at first attempt in 1995.