1954 24 Hours of Le Mans

[3] The ACO again extended the replenishment window (last updated in 1952) of fuel, oil and water from 28 to 30 laps (405 km) although brake fluid was now exempted from this restriction for safety reasons.

[4] After the previous year's intense interest from manufacturers for the new Championship, this year the variety of works teams was reduced: Mercedes had decided to stay focused on F1,[5] Alfa Romeo had closed its racing division, Lancia scratched their team (supposedly daunted by the speed of the Jaguars)[7] and Austin-Healey boycotted the event because of the ongoing presence of the sports-car prototypes.

Low (only 32 inches (810 mm)) and sleek, it was extremely fast: the 3.4-litre straight-6 engine was redesigned and tilted at 8 degrees (to reduce height, like the Mercedes-Benz 300 SL had done)[2] and developed 250 bhp with a top speed over 270 km/h.

The driver line-up was kept pretty much the same from 1953 with winners Tony Rolt / Duncan Hamilton, and 2nd place Stirling Moss / Peter Walker.

This year Peter Whitehead was paired with F1 driver Ken Wharton (his former co-driver Ian Stewart was racing with his brother, Graham, at Aston Martin).

An ex-works C-Type was provided for the Belgian Ecurie Francorchamps team when their original car was crashed on the way to the circuit by a Jaguar mechanic.

With three of his best drivers now unavailable – Alberto Ascari was with Lancia, Giuseppe Farina had been injured in the Mille Miglia and Mike Hawthorn's father had just died suddenly[5][12] – Ferrari could still field a top team of drivers: three of them - Umberto Maglioli, José Froilán González and Maurice Trintignant were in the current Ferrari F1 works team.

OSCA had started the year sensationally when a 1500cc MT-4 entered by Cunningham and driven by Stirling Moss and Bill Lloyd won the Sebring 12-hours against far more powerful opposition.

One of the two DB3S spyders had a supercharged 2.9L engine that developed 235 bhp driven by British F1 drivers Reg Parnell and Roy Salvadori, the other was run by Carroll Shelby.

Talbot sent no works team this year but supplied an improved 4.5L engine (now capable of 280 bhp) for the T26 spyders of the three private entries (Levegh, Meyrat, Grignard).

[18] The small British sportscar firm Kieft arrived with two cars to take on the smallest Porsche – bringing the first fibreclass chassis to Le Mans.

Jaguar was able to get an unofficial practice in May on the full track in an unrelated event and Tony Rolt took the prototype D-type round fully 5 seconds faster than Alberto Ascari's lap record from the previous year in the Indy-engined Ferrari.

Overall, the Jaguars had better handling, disc brakes and were faster (Moss was timed at 154.44 mph/278 km/h over the flying kilometre, giving a huge 20 km/h advantage), but the Ferrari had superior power and acceleration.

[20] Unfortunately the Maserati works transporter broke down en route to the track and the car had to be withdrawn as it arrived too late for scrutineering.

[21] Controversially, Gilberte Thirion qualified the 2-litre works Gordini but was excluded from competing because of her gender (only three years after the Coupe des Dames was awarded to female drivers) – her father drove in her stead in the race.

[16] At 4pm the race was started under dark clouds by Prince Bernhard, consort of Queen Juliana of the Netherlands, and an avid motor-racing fan.

[22] It came as no surprise when the mighty 375's of González, Marzotto and Manzon stormed away in 1-2-3 formation at the start, with Moss, Rolt and Wharton (who had a startline collision[23]) in close pursuit.

Meanwhile, Behra's Gordini and Fitch's Cunningham were regularly trading places in the top-10, mimicking the disc-brakes versus power battle at the front.

[16] A number of other cars had been caught out in the rain: On only lap 5 Count Baggio planted the playboy Ferrari right into the Tertre Rouge sandbank and could not dig it out (so Rubirosa never got a chance to drive for his movie-star girlfriend).

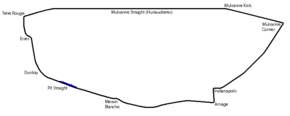

[20] At 9.30pm, the Talbot of Meyrat collided with the Aston Martin of 'Jimmy' Stewart as both were lapping a slower car in the fast section coming up to Maison Blanche.

The car was completely written off and Stewart was very lucky to only suffer a serious arm break (that eventually contributed to his retirement from racing).

[24][26][27] The mid-evening showers caused another flurry of accidents and retirements, including Levegh who was in 8th place when he spun and wrecked his Talbot's suspension.

It joined Moss' car that had become undriveable after he had a total brake failure at the end of the Mulsanne straight doing 160 mph [23] (taking two miles to stop on the escape road with hand-brake and gearbox!

González and Trintignant could afford to take things cautiously, but any unnecessary delays would enable the pursuing Jaguar to open up a chink the Ferrari's armour, and as the rain intensified, the sole remaining D-type piled on the pressure.

[30] But at 10am, Rolt glanced the bank coming out of Arnage lapping a slower car, and 2 minutes were lost in the pits for a bout of impromptu panelbeating.

Around 1pm a ferocious squall slowed all the cars to a snail's pace, then the Jaguar drivers began to close the gap again on Trintignant as the track dried.

González was exhausted (he had not eaten or slept through the weekend[6]) and his lap times dropped to 5'30",[12] but his pit-crew urged him on and as the rain stopped with a half-hour to go, and the track dried out, he was once more able to bring the power of the Ferrari to bear again and extend the gap.

[39] The podium was completed by the American pair, William "Bill" Spear and Sherwood Johnston, in their Cunningham C-4R, who were far behind, 19 laps (over 250 km) back,[40] Briggs himself came in 5th.

Owner-driver René Bonnet and Élie Bayol finished a remarkable 10th overall with a class-distance record (going further than Nuvolari's winning Alfa Romeo 20 years earlier[12]), embarrassing many far-bigger cars left in their wake.