1954 Italian expedition to K2

On the 1954 Italian expedition to K2 (led by Ardito Desio), Achille Compagnoni and Lino Lacedelli became the first people to reach the summit of K2, 8,611 metres (28,251 ft), the second-highest mountain in the world.

Desio felt Italy's earlier exploration of the Karakoram region gave good reason to mount a major expedition which he did on a grand scale, following the American route up the south-east ridge.

Desio considered abandoning the expedition so as to try again by returning later in the year, but weather conditions improved allowing them to edge closer to the top of the mountain.

[1] The mountain had been spotted in 1856 by the Great Trigonometrical Survey to Kashmir,[note 1] and by 1861 Henry Godwin-Austen had reached the Baltoro Glacier and was able to get a clear view of K2 from the slopes of Masherbrum.

[4] The first serious attempt to climb the mountain was in 1902 by a party including Aleister Crowley, who later became notorious as "the Wickedest Man in the World".

The expedition examined ascent routes both north and south of the mountain and made best progress up the north-east ridge before they were forced to abandon their efforts.

[8] Since that time, K2 has developed the reputation of being a more difficult mountain to climb than Mount Everest – every route to the summit is tough.

[14][15] In 1909, the Duke of the Abruzzi expedition again explored various routes before reaching about 6,250 metres (20,510 ft) on the south-east ridge before deciding the mountain was unclimbable.

[1] In 1929, Aimone di Savoia-Aosta, the nephew of the Duke of the Abruzzi, led an expedition to explore the upper Baltoro Glacier, near to K2.

[16] It was only in 1939 that Desio could interest Italy's governing body for mountaineering, the Club Alpino Italiano (CAI), but World War II and the Partition of India delayed things further.

[17] Later, in 1952, Desio travelled to Pakistan as a preliminary for leading a full expedition in 1953 only to discover that the Americans had already booked the single climbing permit for that year.

[21] In Rawalpindi, at the start of his 1953 visit to Pakistan, Desio had met Charlie Houston, leader of the unsuccessful 1953 American Karakoram expedition who was returning from K2.

[22] Even though the American was planning another attempt on the summit for 1954, he was generous in sharing his experience and photographs with Desio, an obvious rival.

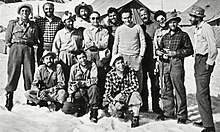

[note 6][29][30] There were to be eleven climbers, all of them Italian, none of whom had been to Himalaya before: Enrico Abram (32 years), Ugo Angelino (32), Walter Bonatti (24), Achille Compagnoni (40), Cirillo Floreanini (30), Pino Gallotti (36), Lino Lacedelli (29), Mario Puchoz (36), Ubaldo Rey (31), Gino Soldà (47) and Sergio Viotto [it] (26).

The scientific team, in addition to Desio (who was 57 years old), comprised Paolo Graziosi (ethnographer), Antonio Marussi [it] (geophysicist), Bruno Zanettin [it] (petrologist), and Francesco Lombardi (topographer).

That Compagnoni and Lacedelli had reached the summit of K2 was not in dispute – at issue was the extent to which they had depended on support from other climbers high on the mountain, how they had treated Bonatti and Madhi, whether they used oxygen all the way to the top, and whether Desio's book was accurate and fair.

Desio died in 2001 at the age of 104 and, eventually, in 2004 the CAI appointed three experts, called "I Tre Saggi" (the three wise men), to investigate.

Desio took the opportunity of using the aircraft to survey the region's topography and snow conditions, which seemed similar to those in Houston's photographs of the previous year.

Tragedy struck the expedition at an early stage: after Puchoz had descended to Camp II he developed problems with his throat and his condition deteriorated until, despite good medical treatment and ample medicines and oxygen, he died with symptoms of pneumonia on 21 June.

When the storm abated they were able to recover Puchoz's body to Base Camp and on 27 June they ascended to bury him beside the memorial cairn to Art Gilkey who had died on the 1953 American expedition.

For example, on one occasion he pinned up a notice: "Remember if you succeed in scaling the peak – as I am confident you will – the entire world will hail you as champions of your race and your fame will endure throughout your lives and long after you're dead.

[64][85] On 18 July Compagnoni and Rey, followed by Bonatti and Lacedelli, set ropes as high as the American Camp VIII at the base of the summit plateau.

[86] Successive severe storms made progress much slower than expected and Desio wrote to the CAI saying he was contemplating returning to Italy and staging a new assault in the autumn with a smaller team of fresh climbers, but using the existing fixed ropes.

Meanwhile, Compagnoni and Lacedelli would establish Camp IX at a lower level of 7,900 metres (25,900 ft) to reduce the height the oxygen needed to be carried.

[91] In the event they established their high camp not at the lower level, where there was deep powdery snow, but at 8,150 metres (26,740 ft) across a difficult traverse over dangerous slab rocks which took almost an hour to achieve.

[94] The Hunzas had not been provided with high-altitude boots and to induce Mahdi to go on higher Bonatti had offered him a cash bonus and had also hinted that he might be allowed to go right up to the summit.

[94] Bonatti dug out a small step in the ice in preparation for an emergency overnight bivouac without a tent or sleeping bags.

Their triumph was very big news in Italy, but internationally it made less impact than the previous year's ascent of Everest, which had been boosted by the coronation of Elizabeth II.

After some recuperation the party left base camp on 11 August[note 19] with Compagnoni going ahead, wanting to hasten to Italy for hospital treatment.

[106][107] The press speculated, mostly correctly, on who had been in the summit party and when Compagnoni flew into Rome in early September he was treated as a hero.