1957 24 Hours of Le Mans

The prospect of an exciting duel between Ferrari, Maserati, Jaguar, Aston Martin and Porsche was enough to draw large crowds to the 24 Hours race, now back at its usual date and reintegrated into the World Championship.

[1] The minimum windscreen height was reduced from 20 to 15 cm, maximum fuel-tank size was 120 litres, and the total fuel usage restrictions were removed a year after they were imposed.

The big talking point with the entry list was the non-appearance of the works Jaguar team, which had retired from racing at the end of the previous year; and the arrival in force of Maserati in the top class.

[11][1] The team had good reason to be confident for outright honours, after Brooks and Cunningham-Reid raced to victory over the Italians in their DBR1/300 at the most recent round of the championship: the 1000km of Nürburgring.

[15] There were also a pair of privately entered 3.5L 290 MM and three 2.0L Testarossas (including Equipe Nationale Belge running a Jaguar, Ferrari and a Porsche to hedge their bets).

[1] Juan Manuel Fangio (who had won at Sebring with Behra in a 450 spyder) was present in the pit, as a ‘reserve driver’ to put concern in the opposition teams.

[17][18][19] France, now a fading force in the major categories was only represented by a pair of Talbot-Maseratis for the Ecurie Dubonnet team and two works Gordinis (as usual, split between the S-3000 and S-2000 classes).

[1] Although Bristol was no longer running, its 2.0L engine was used by Frazer Nash and debutante AC Cars to take on the five medium-engined privateer Ferraris and Maseratis in the S-2000 class.

[1] Colin Chapman had convinced Coventry Climax to develop a short-stroke version of its successful FWA engine (generating 75 bhp) to take on the French in the lucrative Index of Performance (the handicap system which measured cars exceeding their specified target distance by the greatest ratio).

[22] A number of events were held over the race weekend to celebrate the Golden Jubilee of the ACO – postponed as they were from the previous year after the 1955 disaster.

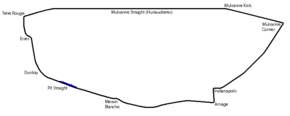

Seventy classic French cars from the very earliest years of the organisation, with drivers in period costume,[23] did demonstration laps of the circuit in a ‘Race of Regularity’ – the winning 1908 Roland-Pillain recorded doing over 50 mph along the Mulsanne straight .

[26] Moss had a major moment when the special new large brakes on his car locked coming up to Mulsanne corner at top speed.

[27] The Whitehead brothers found their new Aston Martin DBR2 was very quick, but deliberately eased off in practice in case team manager Reg Parnell bumped them from the car for his other drivers.

[21] It was also soon apparent that the little French cars would have a fight on their hands this year, as the small Lotus-Climax was proving to be very quick – almost 25 seconds per lap quicker.

[22] His American co-drivers, Herbert MacKay-Fraser and Jay Chamberlain (Lotus’ agent in California) were substituted into the team's S-1100 reserve entry.

The usually quick and nimble Moss was slowed trying to squeeze into his cramped Maserati coupé so the first car to clear the startline was the Ferrari of Peter Collins, leaving a long trail of rubber, followed by the three Aston Martins.

Unfortunately, the final appearance of Talbot was rather ignominious: its transmission broke as it left its start-box and it only went a handful of metres giving its driver, Bruce Halford the shortest debut on record.

At the end of the first hour and 14 laps, Hawthorn had a 40-second lead over the Maseratis of Behra and Moss, then Gendebien, Bueb's Ecosse Jaguar and Brooks in the Aston Martin.

Soon enough, trouble struck more of the Italian cars: Moss’ Maserati began to smoke ominously and heavily, and after 26 laps, just before the two-hour mark, Hawthorn came into the pits to change tyres.

In the fourth hour, Musso, having fought back up to second place, was hobbled by another seized piston destroying his engine out on the Mulsanne straight just before dusk.

With the Severi/Lewis-Evans Ferrari held back with braking problems, this left the Gendebien/Trintignant car as the sole challenger from Maranello, who took over second place from their teammates.

Another casualty in the fourth hour was the second Gordini – the first having only lasted 3 laps – when it pulled into the pits with terminal engine issues.

[19] Then at 1.50am came the most serious accident of the race: Brooks’ Aston Martin, now trailing by two laps and still stuck in 4th gear, was coming out of Tertre Rouge when he lost control, hit the bank and rolled.

Missing from the list was Hamilton's Jaguar that had been delayed around midnight by a burnt-through exhaust pipe which was filling the cockpit with fumes and overheating the fuel lines and burning a hole in the cockpit-floor.

When Hamilton pitted, the exhaust system was welded up and the hole repaired with a plate of steel cut out of an unattended gendarmerie wagon by the “enterprising” pit-crew!

In the Index of Performance, the small Lotus still had a comfortable lead, now ahead of their bigger brother running second and the works Porsche in third.

At three-quarter time (10am), as the fog finally lifted, the order was staying very static – the four Jaguars holding the top places over a 16-lap spread.

Unable to restart and not allowed an assisted start from the pit-crew, the driver set about pushing the car himself: half a mile to the top of the Dunlop hill, to the great cheers of support from the crowd.

Likewise, the Ferrari Testarossa of Ecurie Nationale Belge finishing 7th, won the S-2000 class by 7 laps from the AC Ace and also ahead of the S-1500s whom it had been outperformed by for almost the whole race.

As well as being the only entry for Arnott and DKW, the 1957 race was to be the last appearance for French stalwarts Talbot and Gordini – none of the cars from these manufacturers made it to the end.