1958 24 Hours of Le Mans

The prospect of an exciting duel between Ferrari, Jaguar, Aston Martin and giantkiller Porsche was enough to draw large crowds to the 24 Hours race.

This was an effort to limit the very high speeds of the new Maserati and Ferrari prototypes (and, indirectly ruling out the Jaguars) in the Sportscar Championship.

For the race itself, the Automobile Club de l'Ouest (ACO) allowed an increase of a driver's stint to a maximum of 40 laps (from 36), although the 14-hour total limit was still in place.

[2][1] Following Colin Chapman's example for Lotus in the previous year, many cars adopted the 'wraparound' windscreen to meet the official dimension requirements.

Brian Lister had already been very successful in Britain however his lead driver, Archie Scott-Brown had been tragically killed at a sports-car race at Spa-Francorchamps just three weeks earlier.

Just prior to the meeting, Enzo Ferrari decided not to enter his latest two prototypes, reasoning that his well proven 3-litre 12-cylinder Testa Rossa was just the car for the circuit, and his best drivers.

The pairings mostly came from the Ferrari F1 works team: Mike Hawthorn/Peter Collins, Phil Hill/Olivier Gendebien and Wolfgang von Trips/Wolfgang Seidel (called in to replace Luigi Musso injured in the previous weekend's Belgian Grand Prix).

They entered three of their updated DBR1s, as well as a privateer entry for the Whitehead brothers running a three-year-old Aston Martin DB3S (the runner-up car in 1955[12]).

The strong driver line-up in the works team consisted of Stirling Moss/Jack Brabham, Tony Brooks/Maurice Trintignant and Roy Salvadori/ Stuart Lewis-Evans.

NART had a Ferrari 500 TR, and the British company Peerless entered a true GT car, with a Triumph engine.

There was a big field in the smallest S-750 class and dominated by works entries: defending champions Lotus had two cars; from France were three from Deutsch et Bonnet, four from Monopole and one from specialist VP-Renault.

[9] The 2-litre Lotus 15 proved remarkably quick – Allison and debutante Graham Hill had the 4th and 5th fastest times in practice in a car virtually half the weight of the Ecosse Jaguars.

The first driver away was Moss in his Aston Martin – as lightning-quick off the line as usual – chased by his teammate Brooks and the Jaguars and Ferraris.

Just 4½ minutes after his standing start, Moss came past at the end of the first lap with a quarter-mile, five-second, lead on Hawthorn, Brooks, von Trips, Gendebien and the Aston of Salvadori.

Soon after, the weather (which was to dominate the rest of the race) suddenly changed as an enormous storm swept across the circuit, flooding the track and reducing the visibility to nil.

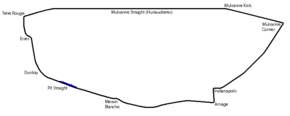

In the 3rd hour Maurice Charles lost control of his Jaguar in the downpour at Maison Blanche and was taken to hospital after being hit by two other cars.

But the worst happened in the twilight just after 10pm when Jean-Marie Brussin (racing under the pseudonym "Mary") lost control of his Jaguar going into the sweeping Dunlop curve after the pits, hitting the earth bank, rolling and ending up near the crest of the rise.

Kessler was fortunate to be thrown clear, receiving only heavy bruising and broken ribs, but Brussin was killed in the accident.

He also keenly listened out for the sound of downshifting gears from cars ahead to get an idea of the approaching Mulsanne corner at the end of the long straight.

[21][22][23] Indeed, around 11.40pm von Trips (in the second-placed Ferrari) came to the high-speed Mulsanne kink and saw wreckage across the track and a driver lying unconscious on the road.

[23] Hill, having taken over from Gendebien, drove exceptionally through the rain to catch and pass Hamilton's co-driver Ivor Bueb to go back into the lead.

Meanwhile, in the Index of Performance, it was a very close race between the works cars of de Tomaso's OSCA and Laureau's DB[17][9] Soon after 6am Trintignant, who had been running a solid 3rd through the night, was stopped by a broken gearbox.

Watched by a crowd, and discreetly advised by his mechanic standing nearby, co-driver Brian Naylor spent over an hour repairing the gearbox on his own and bump-starting it again.

In contrast, both OSCAs finished and claimed a 1-2 success in the Index of Performance, giving both major trophies to Italian cars.

Alejandro de Tomaso subsequently founded his own supercar company in the next year, with his racing wife, Coca-Cola heiress, Elizabeth Isabel Haskell.

Throughout Sunday Stoop and Bolton had battled loose handling, traced to the differential mountings gradually falling apart and had driven very cautiously in the bad weather.

[34][35] In a grim year it also saw the death of Peter Whitehead, killed in an accident when his half-brother was driving in the Tour de France Automobile.

[38] Taken from Quentin Spurring's book, officially licensed by the ACO Championship points were awarded for the first six places in each race in the order of 8-6-4-3-2-1.