1960 Belgian Congo general election

[9] The country was split into nesting, hierarchically organised administrative subdivisions, and run uniformly according to a set "native policy" (politique indigène).

The administration was heavily involved in the life of the Congolese; Belgian functionaries (government civil servants) closely monitored and enforced agricultural production, provided medical services to many residents, and frequently toured even the most rural territories to oversee their subjects.

[11] There was also a high degree of racial segregation between the native and white populations, the latter of which grew considerably after the end of World War II due to immigration from Europe.

While there were no universal criteria for determining évolué status, it was generally accepted that one would have "a good knowledge of French, adhere to Christianity, and have some form of post-primary education.

[13] Since opportunities for upward mobility through the colonial structure were limited, the évolué class institutionally manifested itself in elite clubs through which they could enjoy trivial privileges that made them feel distinct from the Congolese "masses".

[18] That year the association was taken over by Joseph Kasa-Vubu, and under his leadership it became increasingly hostile to the colonial authority and sought autonomy for the Kongo regions in the Lower Congo.

[20] The Belgian government was not prepared to grant the Congo independence and even when it started realising the necessity of a plan for decolonisation in 1957, it was assumed that such a process would be solidly controlled by Belgium.

[26] In October 1958 a group of Léopoldville évolués including Patrice Lumumba, Cyrille Adoula and Joseph Iléo established the Mouvement National Congolais (MNC).

Diverse in membership, the party sought to peacefully achieve Congolese independence, promote the political education of the populace, and eliminate regionalism.

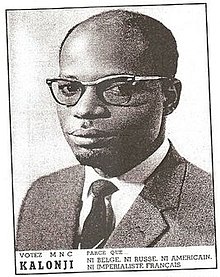

[27] The MNC drew most of its membership from the residents of the eastern city of Stanleyville, where Lumumba was well known, and from the population of the Kasai Province, where efforts were directed by a Muluba businessman, Albert Kalonji.

[28] Belgian officials appreciated its moderate and anti-separatist stance and allowed Lumumba to attend the All-African Peoples' Conference in Accra, Ghana, in December 1958 (Kasa-Vubu was informed that the documents necessary for his travel to the event were not in order and was not permitted to go[29]).

Lumumba was deeply impressed by the Pan-Africanist ideals of Ghanaian president Kwame Nkrumah and returned to the Congo with a more radical party programme.

The mass was infuriated and instead began hurling stones at the police and pillaging European property, initiating three days of violent and destructive riots.

Relations between Lumumba and Kalonji also grew tense, as the former was upset with how the latter was transforming the Kasai branch into an exclusively Luba group and antagonising other tribes.

The party advocated for a strong unitary state, nationalism, and the termination of Belgian rule and began forming alliances with regional groups, such as the Kivu-based Centre du Regroupement Africain (CEREA).

[34] Though the Belgians supported a unitary system over the federal models suggested by ABAKO and CONAKAT, they and more moderate Congolese were unnerved by Lumumba's increasingly extremist attitudes.

With the implicit support of the colonial administration, the moderates formed the Parti National du Progrès (PNP) under the leadership of Paul Bolya and Albert Delvaux.

The security situation in the country deteriorated over the course of the year, especially in the Lower Congo and in Kasai, where violent clashes between Baluba and Lulua were taking place.

Fearing the degeneration of the unrest into a colonial war and facing intense pressure for reform, in late 1959 the Belgian government announced that it would host a round table conference in Brussels in 1960 with the Congolese leadership to discuss the political future of the country.

[37] On the eve of the conference the Congolese delegations banded into a "Common Front" and demanded that all decisions be made binding on the Belgian government and that the Congo be granted immediate independence.

[43] It was decided at the Round Table Conference that the resolutions the participants adopted would serve as the basis for the Loi Fondamentale (Fundamental Law), a temporary draft constitution left for the Congo until a permanent one could be promulgated by a Congolese parliament.

By comparison, the head of state (a President) was irresponsible and only had the power to ratify treaties, promulgate laws, and nominate high ranking officials (including the Prime Minister and the cabinet).

As the Congolese had little experience in democratic processes, few eligible voters in rural areas realised the meaning and importance of an election, and even fewer understood electoral mechanics and procedure.

[50] Frequent attacks on the colonial administration by candidates led to confusion among segments of the electorate, which were given the impression that all forms of government—except welfare services—were to be eliminated after independence.