1965 24 Hours of Le Mans

Despite a strong start, in the end the Fords’ unreliability let them down again and it was an easy victory for Ferrari for the sixth successive year.

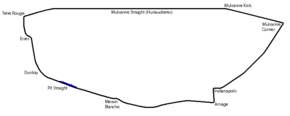

Charles Deutsch, erstwhile French car manufacturer, was the design consultant for the project that eventually became the Bugatti Circuit.

[4] After a slow start to the season, Ferrari introduced the new P2 design from Mauro Forghieri at the April test weekend, and the following 1000 km Monza race.

A range of V12 engines were fitted: The works team had two 4.0-litre 410 bhp open-top cars for F1 world champion John Surtees and former winner Ludovico Scarfiotti, and sports-car specialists Mike Parkes and Jean Guichet.

The North American Racing Team (NART) ran a 365 P2 built around a previous year's P chassis with updated aerodynamics and featured a 4.4 L SOHC V12.

[1] This included NART (Masten Gregory/Jochen Rindt), Maranello Concessionaires (Bianchi/Salmon), Ecurie Francorchamps, Scuderia Filipinetti and Pierre Dumay's private entry.

After the departure of Eric Broadley and Lola Cars, Ford put its racing organisation under Shelby American, with car production and development handled by Kar Kraft in the US and Ford Advanced Vehicles in the UK (run by John Wyer with a number of ex-Aston Martin staff).

Four cars came to Le Mans: FAV used Alan Mann Racing with Innes Ireland / John Whitmore.

Shelby American supported the Rob Walker Racing Team (Maglioli/Bondurant) and the Swiss Scuderia Filipinetti (Müller/Bucknum) who were both also entering Ferraris.

Replacing the destroyed Tipo 59, it left no time to test before the race for its drivers Jo Siffert and Jochen Neerpasch The final big-engine entry was the returning Iso Grifo A3C.

[15] Opposing them were two British cars – a privately entered Elva and the return of the Rover turbine, first seen in the 1963 race, now categorised as equivalent to 1992cc.

It would be driven by F1 drivers Graham Hill and Jackie Stewart[16] Curiously, in the small-engine categories, Alpine was the only French manufacturer present.

Fitted with the 1293cc engine in the Mini-Cooper S they could reach 240 kp/h (148 mph)[18] In the GT classes Ferrari were now the underdog after being beaten by the Shelby Cobras the previous year, and the races since.

[21] Fastest car at the April test-weekend was brand new 330 P2 – John Surtees putting in a lap of 3:35, fully five seconds quicker than the Fords and other Ferraris.

[5][14] Dan Gurney had the quickest GT car – his Shelby Cobra was 12th with a 3:51.3, just ahead of the 3:55.0 of Willy Mairesse in the Belgian Ferrari GTB.

Hill had already fallen away with clutch problems costing 40 minutes in the pits and the French Ford had broken its gearbox when Trintignant had missed a gearchange.

His Triumph Spitfire was the same car that had careered towards the pits in the previous year's race when Mike Rothschild had been overcome by exhaust fumes.

During the night, all of the P2s got delayed by cracks in their brake discs, which in turn gave problems in suspension, each losing 30-60 minutes or more in getting the issues fixed.

Coming up to half-time, the Gurney/Grant car's motor mounts began to crack and the strain of the engine vibration eventually broke the crankshaft.

By halfway, the surprise leader was the French privateer Pierre Dumay chased hard by the NART car of Gregory/Rindt (catching them by at least 5 seconds a lap after the earlier delay[1][30]) and the Ecurie Francorchamps GTB of “Beurlys”/Mairesse.

[32] Soon before 8am the Alpine of previous class-winner Roger Delageneste and veteran Jean Vinatier was retired with ignition problems when comfortably leading the class and running 16th overall.

This had just followed the loss of the smallest car in the field, the fellow works Alpine M63B that had been leading the Thermal Index, when it was stopped by a broken conrod.

With less than three hours to go the little Austin-Healey Sprite of Rauno Aaltonen and Clive Baker, which was looking good for the two Index prizes after the demise of the Alpines, broke its gearbox.

In fifth was their GT stablemate of Gerd Koch / Toni Fischhaber, who in turn won the Index of Thermal Efficiency, despite having to be pushed over the line.

[26][24][6] After losing nearly two hours replacing their clutch in the middle of the night, the NART Ferrari of Rodriguez/Vaccarella was the only P2 to finish, coming in 7th, 28 laps behind the winner.

After a collision with an Alfa Romeo around midnight while running 5th, they had nursed their battered car with oil-pressure issues to the end over 30 laps behind the GT-winning Ferrari.

It covered a lesser distance than in 1963, as an early off by Hill had sucked sand into the engine causing constant overheating issues.

It was a notable experiment, however the issues with fuel consumption and heat management meant the project was impractical for road application and was subsequently cancelled.

[16][6] In a race of attrition there were only fourteen finishers, with British cars filled the final five places including two class wins.

[38] Taken from Quentin Spurring's book, officially licensed by the ACO As calculated after Le Mans, Round 8 of 9, with the best 6 results counting (full score in brackets)