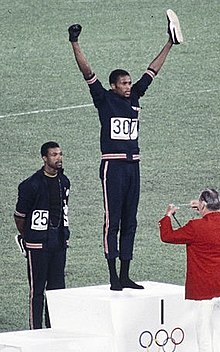

1968 Olympics Black Power salute

During their medal ceremony in the Olympic Stadium in Mexico City on October 16, 1968, two African-American athletes, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, each raised a black-gloved fist during the playing of the US national anthem, "The Star-Spangled Banner".

While on the podium, Smith and Carlos, who had won gold and bronze medals respectively in the 200-meter running event of the 1968 Summer Olympics, turned to face the US flag and then kept their hands raised until the anthem had finished.

For this reason, Carlos raised his left hand as opposed to his right, differing from the traditional Black Power salute.

[9] When "The Star-Spangled Banner" played, Smith and Carlos delivered the salute with heads bowed, a gesture which became front-page news around the world.

[13] A spokesman for the IOC said Smith and Carlos's actions were "a deliberate and violent breach of the fundamental principles of the Olympic spirit.

[1] In 2013, the official IOC website stated that "Over and above winning medals, the black American athletes made names for themselves by an act of racial protest.

[20] Brent Musburger, a writer for the Chicago American before rising to prominence at CBS Sports and ESPN, described Smith and Carlos as "a couple of black-skinned storm troopers" who were "ignoble," "juvenile," and "unimaginative.

"[21] One of the few individuals to publicly defend the actions of Smith and Carlos was Robert D. Clark, then-president of San Jose State University, where both athletes were students.

[22] Smith continued in athletics, playing in the NFL with the Cincinnati Bengals[23] before becoming an assistant professor of physical education at Oberlin College.

[28] Silver medalist Norman, who was sympathetic to his competitors' protest, was reprimanded by his country's Olympic authorities, and he was criticized and ostracized by conservatives in the Australian media.

In an article, Small noted that the athletes of the British team attending the 2008 Olympics in Beijing had been asked to sign gagging clauses which would have restricted their right to make political statements but that they had refused.

"[40] In 2005, San Jose State University honored former students Smith and Carlos with a 22-foot-high (6.7 m) statue of their protest titled Victory Salute, created by artist Rigo 23.

[41] A student, Erik Grotz, initiated the project; "One of my professors was talking about unsung heroes and he mentioned Tommie Smith and John Carlos.

Peter Norman is not included in the monument so viewers can be in his place; there is a plaque in the empty spot inviting those to "Take a Stand".

Their track pants and jackets are a mosaic of dark blue ceramic tiles, while the stripes of the tracksuits are detailed in red and white.

In January 2007, History San Jose opened a new exhibit called Speed City: From Civil Rights to Black Power, covering the San Jose State athletic program "from which many student athletes became globally recognized figures as the Civil Rights and Black Power movements reshaped American society.

"[45] In 2002, San Jose State students and faculty embedded the Victory Salute statue into their Public Art as Resistance project.

A large mural depicting Smith and Carlos stood in the African-American neighborhood of West Oakland, California on an abandoned gas station shed at the corner of 12th Street and Mandela Parkway.

[47] The National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC, which opened in 2016, features a statue of all three athletes on the podium.

[52] Indigenous Australian athlete and former politician Nova Peris called the statue "long overdue" and posed for a photo alongside it with her children, all raising their fists to replicate the original salutes.