1989 Polish parliamentary election

These actions shook the communist regime of the country to such an extent that it decided to begin talking about recognising Solidarity (Polish: Solidarność), an "unofficial" labor union that subsequently grew into a political movement.

The second, much bigger wave of strikes (August 1988) surprised both the government and top leaders of Solidarity, who were not expecting actions of such intensity.

These strikes were mostly organized by local activists, who had no idea that their leaders from Warsaw had already started secret negotiations with the communists.

[8] An agreement was reached by the communist Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR) and the Solidarity movement during the Round Table negotiations.

As a result, real political power was vested in a newly created bicameral legislature (the Sejm, with the recreated Senate), whilst the office of president was re-established.

[9][10] Soon after the agreement was signed, Solidarity leader Lech Wałęsa travelled to Rome to be received by the Polish Pope John Paul II.

[10] Perhaps the most important decision reached during the Round Table talks was to allow for partially free elections to be held in Poland.

[11] In addition, all 35 seats elected via the national electoral list were reserved for the PZPR's candidates provided they gained a certain quota of support.

[11] Although censorship was still in force, the opposition was allowed to campaign much more freely than before, thanks to a new newspaper, Gazeta Wyborcza, and the reactivation of Tygodnik Solidarność.

[12] The communist government still had control over most major media outlets and employed sports and television celebrities as candidates, as well as successful local personalities.

[13] Some members of the opposition were worried that such tactics would gain enough votes from the less educated[citation needed] segment of the population to give the communists the legitimacy that they craved.

Only a few days before June 4, the party Central Committee was discussing the possible reaction of the Western world should Solidarity not win a single seat.

At the same time, the Solidarity leaders were trying to prepare some set of rules for the non-party MPs in a communist-dominated parliament, as it was expected that the party would not win more than 20 seats.

[27] The National list was elected in a similar format to previous Polish elections; voters were presented with a single slate of candidates, all belonging to the PZPR and its satellite parties;[23] Solidarity was invited to submit candidates to the national list, but declined this invitation.

This explains low turnout in the second round as pro-opposition voters (the majority of the electorate) had limited interest in these races; however, Solidarity gave its endorsement to 55 candidates of pro-government parties, including 21 from the PZPR, who ran in opposition to their own party's leadership, and encouraged its supporters to vote for them.

[16] The magnitude of the Communist coalition's defeat was so great that there were initially fears that either the PZPR or the Kremlin would annul the results.

In turn, he nominated General Czesław Kiszczak for prime minister; they intended for Solidarity to be given a few token positions for appearances.

On the international level, this election is seen as one of the major milestones in the fall of communism ("Autumn of Nations") in Central and Eastern Europe.

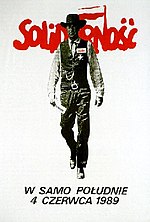

Solidarity Citizens' Committee election poster by Tomasz Sarnecki.