1990 Nebraska gubernatorial election

Orr's popularity had suffered due to changes in the state's income-tax structure enacted in 1987, which were seen as a violation of her pledge not to increase taxes.

In the Republican primary, she easily defeated "perennial candidate" Mort Sullivan,[1] but her winning margin was significantly smaller than expected.

It was suggested that a winter storm on the day of the election might have contributed to Orr's defeat, by reducing turnout among elderly and rural voters.

In 1986, Republican Kay Orr, who had been Nebraska's state treasurer for five years, defeated Democrat Helen Boosalis for the governorship.

[3] In 1987, at Orr's urging, the state legislature passed LB773, which changed Nebraska's method of calculating its personal income tax.

[6] In 1983, during the tenure of governor Bob Kerrey, Nebraska had joined Arkansas, Kansas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma to form the Central Interstate Low-Level Radioactive Waste Compact, under which a single disposal site would be constructed for all five states.

Proponents maintained that the measure would lessen inequality among school districts and would avert a significant increase in property taxes; they also noted that courts in several other states had struck down locally financed educational systems such as Nebraska's.

[20][23] Harris and Hoppner both declared themselves supporters of abortion rights, and were endorsed by the pro-choice organization Nebraska Voters for Choice.

Nelson also declared himself an opponent of abortion, but said that if the legislature passed abortion-rights legislation, he would neither veto nor sign it, allowing it to become law without his signature.

[30] Nelson was criticized for accepting large contributions from insurance companies in Chicago and California;[24] he had also loaned his campaign over $360,000, a sum far greater than that borrowed by any of the other candidates.

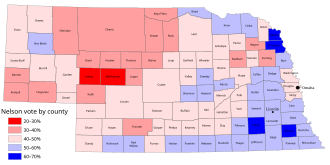

In this election, however, every Democratic vote had to be sought, which made it necessary to direct campaign efforts to the Third Congressional District, consisting of the western three-quarters of the state.

Boyle's was based on securing a strong lead in Omaha, from voters who had supported him as mayor, and on doing well among conservative Democrats in the Third District, attracted by his pro-life stance and endorsements.

[33] Nelson's strategy was the most focused on the Third District: his campaign's goal was to minimize his losing margin in Omaha and Lincoln, while winning heavily in rural Nebraska.

The state's largest newspaper, the Omaha World-Herald, which then circulated throughout Nebraska, endorsed Harris, noting in particular his opposition to gambling.

[40] Boyle led Hoppner in Douglas County by 11,000 votes, and until about midnight he held the lead; however, his support outside of the Omaha area was not strong, and he was forced to admit defeat soon thereafter.

[27] On the morning of May 16, Hoppner and Nelson were virtually tied, with only a few hundred votes between them, absentee ballots still to be counted, and a recount almost certain to be held, as required by state law for cases when two leading candidates were within one percentage point of one another.

[27] The recount in fact proved necessary; and so close was the contest that only on July 3, some 48 days after the election, was Nelson certified the winner,[41] by a margin of 41 votes: 44,556 to Hoppner's 44,515.

[57] In July, Nelson announced that he would not seek re-election to First Executive's board when his term expired at the end of the month, stating that his campaign would not leave him time to fulfill his duties as a director, and that his resignation had nothing to do with the company's history of junk-bond dealings.

[58] In September, Orr's campaign ran a commercial stating that Nelson, as a consultant and director of the company, must have been involved in its decisions to invest in junk bonds.

[59] Nelson declared that Orr had "resorted to negative campaigning in order to save her job",[56] and denied any relationship with Milken.

Nelson declined to do so, for reasons of "privacy and security",[60] declaring that he had provided all the records required by the law, and accusing Orr of demanding them as a diversionary tactic.

Orr ran radio commercials in support of the repeal, calling the bill "a record tax increase" and noting that she had vetoed it.

[53] In July 1990, Kerrey withdrew his support from the proposed radioactive-waste repository in Boyd County, asserting that the facility might no longer be needed and might not be economically feasible.

[72] Orr accused Nelson of "lacking leadership" on abortion, declaring that she would veto any bill that relaxed restrictions on the procedure.

Nelson supported the measure, and stated that if elected, he would propose an amendment to the Nebraska constitution that would authorize a statewide lottery.

A similar pattern obtained on other stations in Omaha, Lincoln, North Platte, and Sioux City, with Creative Media actually purchasing between 12% and 88% of the time ordered by the campaign.

[81][82] On November 6, the day of the election, a winter storm struck central Nebraska, depositing up to 12 inches (300 mm) of snow and ice.

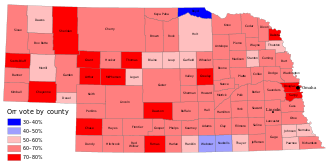

In a race for an open House seat in the Third District, Republican Bill Barrett defeated Democrat Sandra K. Scofield, taking 51.1% of the vote to her 48.8%.

[75][93] Nationally, the Democratic Party made small gains in the U.S. Congress, with an increase of one seat in the Senate and eight in the House of Representatives.

[94][95] Governors who had reneged on pledges not to allow tax increases suffered badly; beside Orr, Republicans Mike Hayden of Kansas and Bob Martinez of Florida were rejected by the voters.