19th century in science

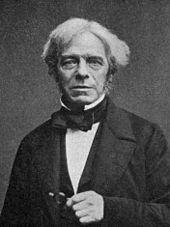

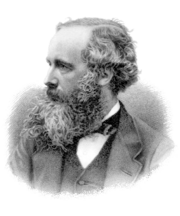

In physics, the experiments, theories and discoveries of Michael Faraday, Andre-Marie Ampere, James Clerk Maxwell, and their contemporaries led to the creation of electromagnetism as a new branch of science.

Elliptic geometry was developed later in the 19th century by the German mathematician Bernhard Riemann; here no parallel can be found and the angles in a triangle add up to more than 180°.

Hermann Grassmann in Germany gave a first version of vector spaces,[9] William Rowan Hamilton in Ireland developed noncommutative algebra.

Niels Henrik Abel, a Norwegian, and Évariste Galois, a Frenchman, proved that there is no general algebraic method for solving polynomial equations of degree greater than four (Abel–Ruffini theorem).

In the later 19th century, Georg Cantor established the first foundations of set theory, which enabled the rigorous treatment of the notion of infinity and has become the common language of nearly all mathematics.

[14] Cantor's set theory, and the rise of mathematical logic in the hands of Peano, L. E. J. Brouwer, David Hilbert, Bertrand Russell, and A.N.

[21] A year later, Thomas Young demonstrated the wave nature of light—which received strong experimental support from the work of Augustin-Jean Fresnel—and the principle of interference.

[27] A year later, botanist Robert Brown discovered Brownian motion: pollen grains in water undergoing movement resulting from their bombardment by the fast-moving atoms or molecules in the liquid.

[28] In 1829, Gaspard Coriolis introduced the terms of work (force times distance) and kinetic energy with the meanings they have today.

[29] In 1841, Julius Robert von Mayer, an amateur scientist, wrote a paper on the conservation of energy but his lack of academic training led to its rejection.

[36] There were important advances in continuum mechanics in the first half of the century, namely formulation of laws of elasticity for solids and discovery of Navier–Stokes equations for fluids.

The relation between heat and energy was important for the development of steam engines, and in 1824 the experimental and theoretical work of Sadi Carnot was published.

[39] Kelvin and Clausius also stated the second law of thermodynamics, which was originally formulated in terms of the fact that heat does not spontaneously flow from a colder body to a hotter.

[40] The second Law was the idea that gases consist of molecules in motion had been discussed in some detail by Daniel Bernoulli in 1738, but had fallen out of favor, and was revived by Clausius in 1857.

The encapsulation of heat in particulate motion, and the addition of electromagnetic forces to Newtonian dynamics established an enormously robust theoretical underpinning to physical observations.

[46] The prediction that light represented a transmission of energy in wave form through a "luminiferous ether", and the seeming confirmation of that prediction with Helmholtz student Heinrich Hertz's 1888 detection of electromagnetic radiation, was a major triumph for physical theory and raised the possibility that even more fundamental theories based on the field could soon be developed.

Experimental confirmation of Maxwell's theory was provided by Hertz, who generated and detected electric waves in 1886 and verified their properties, at the same time foreshadowing their application in radio, television, and other devices.

[50] The kinetic theory in turn led to the statistical mechanics of Ludwig Boltzmann (1844–1906) and Josiah Willard Gibbs (1839–1903), which held that energy (including heat) was a measure of the speed of particles.

[52] In 1902, James Jeans found the length scale required for gravitational perturbations to grow in a static nearly homogeneous medium.

Although the concept of the atom dates back to the ideas of Democritus, John Dalton formulated the first modern description of it as the fundamental building block of chemical structures.

Dalton developed the law of multiple proportions (first presented in 1803) by studying and expanding upon the works of Antoine Lavoisier and Joseph Proust.

(1791–1867)

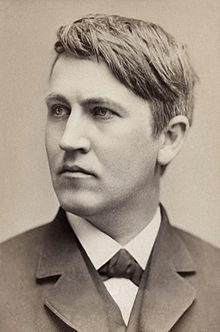

(1824–1907)

(1831–1879)