Wedding of Prince William and Catherine Middleton

John Hall, Dean of Westminster, presided at the service; Rowan Williams, Archbishop of Canterbury, conducted the marriage; Richard Chartres, Bishop of London, preached the sermon; and a reading was given by Catherine's brother James.

As William was not the heir apparent to the throne at the time, the wedding was not a full state occasion, and details such as much of the guest list of about 1,900 were left for the couple to decide.

The occasion was made a public holiday in the United Kingdom and featured many ceremonial aspects, including use of the state carriages and roles for the Foot Guards and Household Cavalry.

[15][16] Following the announcement, the couple gave an exclusive interview to ITV News political editor Tom Bradby[17] and hosted a photocall at St James's Palace.

[34] TV programmes were also shown in the UK prior to the wedding which provided deeper insights into the couple's relationship and backgrounds, including When Kate Met William[35] and Channel 4's Meet the Middletons.

[36] On 5 January, St James's Palace publicised that the ceremony would start at 11:00 British Summer Time (BST) and that Catherine would arrive at the abbey by car rather than by carriage, the traditional transport for royal brides.

[43] The British government tourist authority VisitBritain predicted the wedding would trigger a tourism boom that would last several years, eventually pulling in an additional 4 million visitors and generating £2 billion.

[44] However, VisitBritain's head of research and forecasting, David Edwards, suggested to colleagues two days after the engagement was announced that the evidence pointed to royal weddings having a negative impact on inbound tourism.

[51] The bridal party, which had spent the night at the Goring Hotel,[52] left for the ceremony in the former number one state Rolls-Royce Phantom VI at 10.52 am,[53] in time for the service to begin at 11.00 am.

A prominent decorative addition inside the abbey for the ceremony was an avenue of 20-foot tall trees, six field maples and two hornbeams, arranged on either side of the main aisle.

[71] Her hair was loosely curled in a half-up, half-down style by the Richard Ward Salon[65] with a deep side part and a hairpiece made of ivy and lily of the valley to match Catherine's bouquet.

[78] The pages wore a gold and crimson sash (with tassel) around their waists, as is tradition for officers in the Irish Guards when in the presence of a member of the Royal Family.

While military dress uniforms do not traditionally have pockets, the palace requested that some sort of compartment be added to Harry's outfit for Catherine's wedding ring.

[85] The Dean of Westminster, John Hall, officiated for most of the service, with Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury, as celebrant of the marriage and Richard Chartres, the Bishop of London, preaching the sermon.

[54] On leaving Westminster Abbey, to the pealing of bells, they passed through a guard of honour of individually selected men and women from the various services, and were greeted by cheers from the crowds.

[101][102] Fanfare ensemble leader Wing Commander Duncan Stubbs's own composition Valiant and Brave was performed as the royal couple signed the wedding registers.

[97] Preux et audacieux (which translates from French as "Valiant and Brave") is the motto of 22 Squadron, in which Prince William was serving as a search and rescue pilot at RAF Valley in North Wales.

[103] The fanfare led into the recessional music, the orchestral march "Crown Imperial" by William Walton, composed for the coronation of George VI and which was also performed at Charles and Diana's wedding.

[104] The music performed before the service included two instrumental pieces by Sir Peter Maxwell Davies ("Veni Creator Spiritus" and "Farewell to Stromness"), as well as works by Johann Sebastian Bach, Benjamin Britten, Frederick Delius, Edward Elgar, Gerald Finzi, Charles Villiers Stanford, Ralph Vaughan Williams and Percy Whitlock.

[105] Catherine's Welsh gold wedding ring[106][107] was made by the royal warrant holder Wartski, a company with roots in Bangor, Gwynedd, north Wales.

Additionally, McVitie's made a chocolate biscuit groom's cake from a Royal Family recipe, specially requested by Prince William, for the reception at Buckingham Palace.

The car, a blue, two-seater Aston Martin DB6 Volante (MkII convertible) that had been given to Prince Charles by the Queen as a 21st birthday present, was decorated in the customary newlywed style by the best man and friends; the rear number plate read "JUST WED".

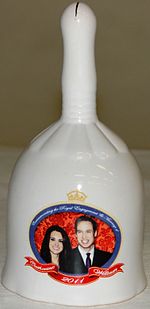

[138] Prince William and Catherine Middleton personally approved an official range of china (including handmade plates, cups, and pill boxes) to be made for the Royal Collection and sold as souvenirs from December 2010 onwards.

"[140] The Lord Chamberlain's office approved a longer list of memorabilia, including official mugs, plates, biscuit tins, and porcelain pill pots.

[144] The Royal Canadian Mint released a series of coins, and Canada Post issued a stamp,[145] approved by Clarence House, in commemoration of the wedding.

[163] An April 2011 poll of 2,000 British adults found that 35% of the public intended to watch the wedding on television while an equal proportion planned to ignore the event altogether.

[190] Criticism and scepticism stemmed from the belief that, at a time of recession and rising unemployment in the UK, millions of pounds in tax funds were used for the wedding's security.

[227] The English Defence League vowed to hold a counter-demonstration and promised 50 to 100 EDL members at each railway station in central London to block Muslim extremists in a "ring of steel".

[229] On 28 April 2011, political activist Chris Knight and two others were arrested by the Metropolitan Police Service "on suspicion of conspiracy to cause public nuisance and breach of the peace".

In Scotland, twenty-one people were arrested at an unofficial "street party" in Kelvingrove Park, Glasgow which saw "completely unacceptable levels" of drunkenness according to Strathclyde Police.