61 Cygni

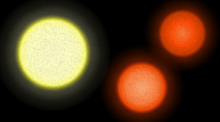

Of apparent magnitude 5.20 and 6.05, respectively, they can be seen with binoculars in city skies or with the naked eye in rural areas without light pollution.

[note 1][16][17] Over the course of the twentieth century, several different astronomers reported evidence of a massive planet orbiting one of the two stars, but recent high-precision radial velocity observations have shown that all such claims were unfounded.

61 Cygni is relatively dim, so it does not appear on ancient star maps, nor is it given a name in western[19] or Chinese systems.

William Herschel began systematic observations of 61 Cygni as part of a wider study of binary stars.

[27] In 1792, Giuseppe Piazzi noticed the high proper motion when he compared his own observations of 61 Cygni with those of Bradley, made 40 years earlier.

[30] Piazzi noted that this motion meant that it was probably one of the closest stars, and suggested it would be a prime candidate for an attempt to determine its distance through parallax measurements, along with two other possibilities, Delta Eridani and Mu Cassiopeiae.

[27] When Joseph von Fraunhofer invented a new type of heliometer, Bessel carried out another set of measurements using this device in 1837 and 1838 at Königsberg.

[34] Bessel continued to make additional measurements at Königsberg, publishing a total of four complete observational runs, the last in 1868.

[35] Only a few years after Bessel's measurement, in 1842 Friedrich Wilhelm Argelander noted that Groombridge 1830 had an even larger proper motion, and 61 Cygni became the second highest known.

[38] In 1911, Benjamin Boss published data indicating that the 61 Cygni system was a member of a comoving group of stars.

[40][41] Observations taken by planet search programs show that both components have strong linear trends in the radial velocity measurements.

[note 2] This is well within the capability for aperture of typical binoculars, though to resolve the binary these need a steady mount and some 10x magnification.

61 Cygni A is the fourth-nearest star that is visible to the naked eye for mid-latitude northern observers, after Sirius, Epsilon Eridani, and Procyon A.

[note 3] The leisurely orbit of the pair has made it difficult to pin down their respective masses, and the accuracy of these values remain somewhat controversial.

The compactness of the astrosphere is likely due to the low mass outflow and the relatively high velocity through the local interstellar medium.

[57] However, a 2008 evolutionary model using the CESAM2k code from the Côte d'Azur Observatory gives an age estimate of 6.0 ±1.0 Gyr for the pair.

Kaj Strand of the Sproul Observatory, under the direction of Peter van de Kamp, made the first such claim in 1942 using observations to detect tiny but systematic variations in the orbital motions of 61 Cygni A and B.

[62] In 1978, Wulff-Dieter Heintz of the Sproul Observatory proved that these claims were spurious, as they were unable to detect any evidence of such motion down to six percent of the Sun's mass—equivalent to about 60 times the mass of Jupiter.

[65] The habitable zone for 61 Cygni A, defined as the locations where liquid water could be present on an Earth-like planet, is 0.26–0.58 AU.

Both stars were selected by NASA as "Tier 1" targets for the proposed optical Space Interferometry Mission.

[68] This mission is potentially capable of detecting planets with as little as 3 times the mass of the Earth at an orbital distance of 2 AU from the star.