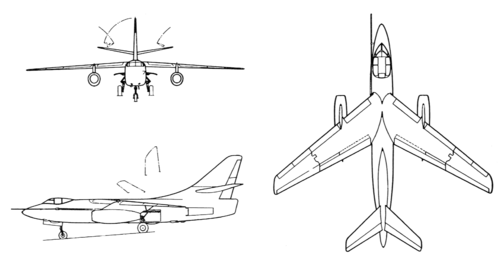

Douglas A-3 Skywarrior

Initially used in the nuclear-armed strategic bomber role, the emergence of effective ballistic missiles led to this mission being deprioritized by the early 1960s.

Throughout the majority of its later service life, the Skywarrior was tasked with various secondary missions which included use as an electronic warfare platform, tactical reconnaissance aircraft, and high-capacity aerial refueling tanker.

A modified derivative of the Skywarrior, the B-66 Destroyer, served in the United States Air Force, where it was operated as a tactical bomber, electronic warfare aircraft, and aerial reconnaissance platform up until its withdrawal during the 1970s.

Success encouraged further development of the concept; early in the post-war years, officials within the USN began to investigate the use of jet power as a potential means of operating larger carrier-based aircraft that would be capable of performing the strategic bombing mission.

[3] In January 1948, the Chief of Naval Operations issued a requirement to develop a long-range, carrier-based attack plane that could deliver either a 10,000 lb (4,500 kg) bomb load or a nuclear weapon.

[4] The envisioned aircraft was intended to be operated from the planned United States-class "supercarriers," which were significantly larger than the USN's existing carriers, thus the specification set a target loaded weight of 100,000 lb (45,000 kg).

Additionally, the USN sought for this bomber to possess greater speed and range than its existing North American AJ Savage fleet.

[5] Ed Heinemann, Douglas' chief designer, later to win fame for the A-4 Skyhawk, fearing that the United States class was vulnerable to cancellation, proposed a significantly smaller aircraft of 68,000 lb (31,000 kg) loaded weight, capable of operating from the USN's existing carriers.

[6][7] Heinemann had reasoned (correctly) that as technology developed, the size and weight of nuclear weapons would substantially decrease, which increased the rationale for designing a more compact bomber.

[5] During July 1949, the USN, recognizing the suitability of Douglas' design, awarded a contract for the production of two flight-capable prototypes and a single static airframe to the company.

[9] Even prior to the first flight being conducted, Douglas was considering switching to rival manufacturer Pratt & Whitney's J57 engine, which was heavier, but allowed the overall aircraft to be lighter as it used less fuel.

Early on, the aircraft was found to handle particularly well in flight, in part due to the attention Heinemann and the design team had paid to the hydraulically-boosted control surfaces.

[4] As had been predicted by Heinemann early on, the Skywarrior had been designed to carry larger and bulkier bombs than it ever would in service due to the rapid improvements made in weapons technology.

[11] Despite this, at the Navy's insistence, the aircraft was qualified for an 'overload' payload capacity of 84,000 lb (38,000 kg), the testing of which would establish a weight-related record for carrier operations.

[12] By the end of the 1950s, it was becoming clear that the nuclear mission of the Skywarrior would be passed onto ballistic missiles; however, its high weight clearance and size meant that the aircraft would be useful in various other capacities.

Flight controls were hydraulic, and for storage below deck, the A-3's wings folded outboard of the engines, lying almost flat, and its vertical stabilizer was hinged to starboard.

[4] Efforts to reduce weight to make the aircraft suitable for carrier operations had led to the deletion of ejection seats during the design process for the Skywarrior, based on the assumption that most flights would be at high altitude.

[16] (In 1973, the widow of a Skywarrior crewman killed over Vietnam sued the McDonnell Douglas Aircraft Company for not providing ejection seats in the A-3.

[15]) In contrast, the US Air Force's B-66 Destroyer, not subject to the weight requirements for carrier operations, was equipped with ejection seats throughout its service life.

[17] The Skywarrior could carry up to 12,000 lb (5,400 kg) of weaponry in the fuselage bomb bay, which in later versions was used for sensor and camera equipment or additional fuel tanks.

Defensive armament was two 20mm cannons in a radar-operated tail turret designed by Westinghouse, soon removed in favor of electronic countermeasure equipment.

Soon afterward, the Navy abandoned the concept of carrier-based strategic nuclear weaponry for the successful Polaris missile-equipped Fleet Ballistic Missile submarine program and all A-5As were converted to the RA-5C Vigilante reconnaissance variant.

[19] Eventually, the EKA-3B was replaced by the smaller dedicated Grumman KA-6D Intruder tanker, which although it had less capacity and endurance, was deployed in greater numbers within the carrier's air wing.

The EA-3 variant was used in critical electronic intelligence (ELINT) roles operating from aircraft carrier decks and ashore supplementing the larger Lockheed EP-3.

These ambitions were ultimately unsuccessful when Vice Admiral Richard Dunleavy, as Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Air Warfare and a former A-3 bombardier/navigator himself, made the final decision to retire the type.

As the plan matured, two other contractors, Thunderbird Aviation and CTAS also elected to participate in similar agreements, with eleven A-3s spread between the five operators.