A. Merritt

As editor, he hired the unheralded new artists Virgil Finlay and Hannes Bok and promoted the work done on polio by Sister Elizabeth Kenny.

His financial success allowed him to pursue world travel—he invested in real estate in Jamaica and Ecuador—and exotic hobbies, like cultivating orchids and plants linked to witchcraft and magic (monkshood, wolfbane, blue datura, peyote, and cannabis).

[5] He was described as a hypochondriac who talked endlessly about his medical symptoms, and showed eccentric behavior like a need to try out any food, tobacco and medicine he found on his coworkers desks.

He lived in the Hollis Park Gardens neighborhood of Queens, New York City, where he accumulated collections of weapons, carvings, and primitive masks from his travels, as well as a library of occult literature that reportedly exceeded 5000 volumes.

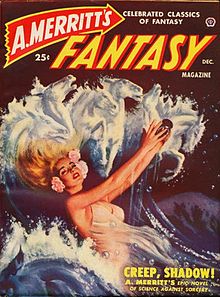

[11] Other short stories and serial novels followed in the Munsey magazines All-Story, Argosy All-Story, and Argosy:[a] The People of the Pit (1918), "The Moon Pool" (1918), The Conquest of the Moon Pool (1919), "Three Lines of Old French" (1919), The Metal Monster (1920), The Face in the Abyss (1923), The Ship of Ishtar (1924), Seven Footprints to Satan (1927), The Snake Mother (1930), Burn Witch Burn!

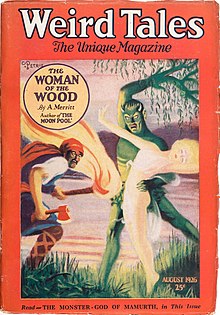

[11] Meanwhile, rather few of his stories appeared elsewhere: The Pool of the Stone God (in his own American Weekly, 1923), The Woman of the Wood (Weird Tales, 1926), The Metal Emperor (Science and Invention, 1927), and The Drone Man (Fantasy Magazine, 1934).

The Fox Woman and the Blue Pagoda (1946) combined an unfinished story with a conclusion written by Merritt's friend Hannes Bok.

[12] Merritt was a major influence on H. P. Lovecraft[13][14] and Richard Shaver,[15] and highly esteemed by his friend and frequent collaborator Hannes Bok, a science fiction illustrator.