ALICE experiment

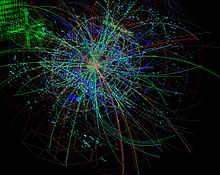

These collisions mimic the extreme temperature and energy density that would have been found in the fractions of a second after the Big Bang by forming a quark–gluon plasma, a state of matter in which quarks and gluons are unbound.

[2] Understanding quark deconfinement and the properties of quark-gluon plasma are key issues in quantum chromodynamics (QCD) and the study of physics of strongly interacting matter.

[10][11] Today's program at these laboratories has moved on to ultra-relativistic collisions of heavy ions, and it is just reaching the energy threshold at which the phase transition is expected to occur.

[citation needed] When the two lead nuclei collide, matter undergoes a transition to briefly form a droplet of quark–gluon plasma, which is believed to have filled the universe a few microseconds after the Big Bang.

The droplet of QGP instantly cools, and the individual quarks and gluons (collectively called partons) recombine into a mixture of ordinary matter that speeds away in all directions.

[13][14] The first collisions in the center of the ALICE, ATLAS, and CMS detectors took place less than 72 hours after the LHC ended its first run of protons and switched to accelerating lead-ion beams.

[15] The experiment was conducted by counter-rotating beams of protons and lead ions, and begun with centered orbits with different revolution frequencies, and then separately ramped to the accelerator's maximum collision energy.

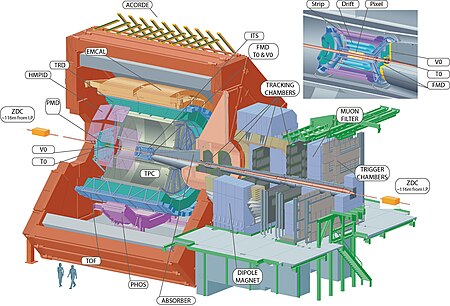

This is done by using particles, created inside the hot volume as it expands and cools down, that live long enough to reach the sensitive detector layers situated around the interaction region.

[21] The upgraded ITS will open new channels in the study of the Quark Gluon Plasma formed at LHC which are necessary in order to understand the dynamics of this condensed phase of the QCD.

Finally, the upgraded ITS will give us the chance to characterize the thermal radiation coming from the QGP and the in-medium modification of hadronic spectral functions as related to chiral symmetry restoration.

The velocity dependence of the ionization strength is connected to the well-known Bethe–Bloch formula, which describes the average energy loss of charged particles through inelastic Coulomb collisions with the atomic electrons of the medium.

Inside such a radiator, fast charged particles cross the boundaries between materials with different dielectric constants, which can lead to the emission of TR photons with energies in the X-ray range.

In the ALICE TRD, the TR photons are detected just behind the radiator using MWPCs filled with a xenon-based gas mixture, where they deposit their energy on top of the ionization signals from the particle's track.

The ALICE TRD was designed to derive a fast trigger for charged particles with high momentum and can significantly enhance the recorded yields of vector mesons.

The MRPCs are parallel-plate detectors built of thin sheets of standard window glass to create narrow gas gaps with high electric fields.

These plates are separated using fishing lines to provide the desired spacing; 10 gas gaps per MRPC are needed to arrive at a detection efficiency close to 100%.

The simplicity of the construction allows a large system to be built with an overall TOF resolution of 80 ps at a relatively low cost (CERN Courier November 2011 p8).

Combining such a measurement with the PID information from the ALICE TPC has proved useful in improving the separation between the different particle types, as figure 3 shows for a particular momentum range.

If a dense medium (large refractive index) is used, only a thin radiator layer of the order of a few centimetres is required to emit a sufficient number of Cherenkov photons.

PHOS is a high-resolution electromagnetic calorimeter installed in ALICE[27] to provide data to test the thermal and dynamical properties of the initial phase of the collision.

Photons on the other hand pass through a converter, initiating an electromagnetic shower in a second detector layer where they produce large signals on several cells of its sensitive volume.

[31] The FMD consist of 5 large silicon discs, each with 10,240 individual detector channels to measure the charged particles emitted at small angles relative to the beam.

With ACORDE, the ALICE Experiment has been able to detect muon bundles with the highest multiplicity ever registered as well as to indirectly measure very high energy primary cosmic rays.

[citation needed] ALICE had to design a data acquisition system that operates efficiently in two widely different running modes: the very frequent but small events, with few produced particles encountered during proton-proton collisions and the relatively rare, but extremely large events, with tens of thousands of new particles produced in lead-lead collisions at the LHC (L = 1027 cm−2 s−1 in Pb-Pb with 100 ns bunch crossings and L = 1030-1031 cm−2 s−1 in pp with 25 ns bunch crossings).

The hardware of the ALICE DAQ system[34] is largely based on commodity components: PCs running Linux and standard Ethernet switches for the eventbuilding network.

Finally, the ALICE experiment Mass Storage System (MSS) combines a very high bandwidth (1.25 GB/s) and every year stores huge amounts of data, more than 1 Pbytes.

The physics program of ALICE includes the following main topics: i) the study of the thermalization of partons in the QGP with focus on the massive charming beauty quarks and understanding the behavior of these heavy quarks in relation to the strongly coupled medium of QGP, ii) the study of the mechanisms of energy loss that occur in the medium and the dependencies of energy loss on the parton species, and iii) the dissociation of quarkonium states which can be a probe of deconfinement and of the temperature of the medium and finally the production of thermal photons and low-mass dileptons emitted by the QGP which is about assessing the initial temperature and degrees of freedom of the systems as well as the chiral nature of the phase transition.

[36] ALICE confirmed that the QCD matter created in Pb-Pb collisions behaves like a fluid, with strong collective motions that are well described by hydrodynamic equations.

Further analyses, in particular including the full dependence of these observables on centrality, will provide more insights into the properties of the system – such as initial velocities, the equation of state and the fluid viscosity – and strongly constrain the theoretical modelling of heavy-ion collisions.

To test the possible presence of collective phenomena further, the ALICE collaboration has extended the two-particle correlation analysis to identified particles, checking for a potential mass ordering of the v2 harmonic coefficients.