ATLAS experiment

The ATLAS Collaboration, the international group of physicists belonging to different universities and research centres who built and run the detector, was formed in 1992 when the proposed EAGLE (Experiment for Accurate Gamma, Lepton and Energy Measurements) and ASCOT (Apparatus with Super Conducting Toroids) collaborations merged their efforts to build a single, general-purpose particle detector for a new particle accelerator, the Large Hadron Collider.

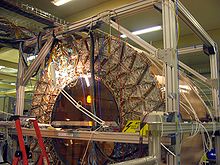

Construction work began at individual institutions, with detector components then being shipped to CERN and assembled in the ATLAS experiment pit starting in 2003.

[10][11][12] The second data-taking period, Run II, was completed, always at 13 TeV energy, at the end of 2018 with a recorded integrated luminosity of nearly 140 fb−1 (inverse femtobarn).

For the processes already known, it is a matter of measuring more and more accurately the properties of known particles or finding quantitative confirmations of the Standard model.

Processes not observed so far would allow, if detected, to discover new particles or to have confirmation of physical theories that go beyond the Standard model.

It was developed in stages throughout the latter half of the 20th century, through the work of many scientists around the world,[17] with the current formulation being finalized in the mid-1970s upon experimental confirmation of the existence of quarks.

Since then, confirmation of the top quark (1995), the tau neutrino (2000), and the Higgs boson (2012) have added further credence to the Standard model.

Although the Standard model is believed to be theoretically self-consistent[18] and has demonstrated huge successes in providing experimental predictions, it leaves some phenomena unexplained and falls short of being a complete theory of fundamental interactions.

The model does not contain any viable dark matter particle that possesses all of the required properties deduced from observational cosmology.

In this field, in addition to the discovery of the Higgs boson, the experimental work of ATLAS has focused on precision measurements, aimed at determining with ever greater accuracy the many physical parameters of theory.

In March 2013, in the light of the updated ATLAS and CMS results, CERN announced that the new particle was indeed a Higgs boson.

[22] These measurements provide indirect information on the details of the Standard Model, with the possibility of revealing inconsistencies that point to new physics.

For these and other reasons, many particle physicists believe it is possible that the Standard Model will break down at energies at the teraelectronvolt (TeV) scale or higher.

The stable particles would escape the detector, leaving as a signal one or more high-energy quark jets and a large amount of "missing" momentum.

Evidence supporting these models might either be detected directly by the production of new particles, or indirectly by measurements of the properties of B- and D-mesons.

[23] Some hypotheses, based on the ADD model, involve large extra dimensions and predict that micro black holes could be formed by the LHC.

[24] These would decay immediately by means of Hawking radiation, producing all particles in the Standard Model in equal numbers and leaving an unequivocal signature in the ATLAS detector.

ATLAS is designed to detect these particles, namely their masses, momentum, energies, lifetime, charges, and nuclear spins.

However, the beam energy and extremely high rate of collisions require ATLAS to be significantly larger and more complex than previous experiments, presenting unique challenges of the Large Hadron Collider.

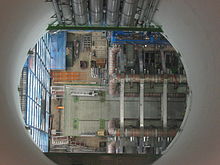

[26] The ATLAS detector[1][2][3] consists of a series of ever-larger concentric cylinders around the interaction point where the proton beams from the LHC collide.

Maintaining detector performance in the high radiation areas immediately surrounding the proton beams is a significant engineering challenge.

It is composed of four double layers of silicon strips, and has 6.3 million readout channels and a total area of 61 square meters.

This is not as precise as those for the other two detectors, but it was necessary to reduce the cost of covering a larger volume and to have transition radiation detection capability.

It functions similarly to the Inner Detector, with muons curving so that their momentum can be measured, albeit with a different magnetic field configuration, lower spatial precision, and a much larger volume.

The ATLAS detector uses two large superconducting magnet systems to bend the trajectory of charged particles, so that their momenta can be measured.

of the magnetic field: Since all particles produced in the LHC's proton collisions are traveling at very close to the speed of light in vacuum

The ATLAS detector is complemented by a set of four sub-detectors in the forward region to measure particles at very small angles.

[34] Earlier particle detector read-out and event detection systems were based on parallel shared buses such as VMEbus or FASTBUS.

In the second data-taking period of the LHC, Run-2, there were two distinct trigger levels:[36] ATLAS permanently records more than 10 petabytes of data per year.

This was revealed by Maximilien Brice, and confirmed by Roger Ruber during interviews in 2020 with Rebecca Smethurst of the University of Oxford.

Muon Spectrometer :

(1) Forward regions (End-caps)

(1) Barrel region

Magnet System :

(2) Toroid Magnets

(3) Solenoid Magnet

Inner Detector :

(4) Transition Radiation Tracker

(5) Semi-Conductor Tracker

(6) Pixel Detector

Calorimeters :

(7) Liquid Argon Calorimeter

(8) Tile Calorimeter