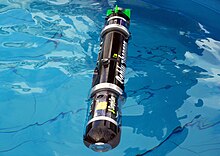

Autonomous underwater vehicle

The first AUV was developed at the Applied Physics Laboratory at the University of Washington as early as 1957 by Stan Murphy, Bob Francois and later on, Terry Ewart.

The "Self-Propelled Underwater Research Vehicle", or SPURV, was used to study diffusion, acoustic transmission, and submarine wakes.

Over the past years, there have been abundant attempts to develop underwater vehicles to meet the challenge of exploration and extraction programs in the oceans.

[2] The oil and gas industry uses AUVs to make detailed maps of the seafloor before they start building subsea infrastructure; pipelines and sub sea completions can be installed in the most cost effective manner with minimum disruption to the environment.

A variety of sensors can be affixed to AUVs to measure the concentration of various elements or compounds, the absorption or reflection of light, and the presence of microscopic life.

Though the Seaglider was originally designed for oceanographic research, in recent years it has seen much interest from organizations such as the U.S. Navy or the oil and gas industry.

The fact that these autonomous gliders are relatively inexpensive to manufacture and operate is indicative of most AUV platforms that will see success in myriad applications.

[4][weasel words][vague][clarification needed] An example of an AUV interacting directly with its environment is the Crown-Of-Thorns Starfish Robot (COTSBot) created by the Queensland University of Technology (QUT).

The COTSBot finds and eradicates crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci), a species that damages the Great Barrier Reef.

The RangerBot was developed for single person deployment and offers real-time on-board vision for navigation, obstacle detection, and management tasks.

As a consequence of limited resources and inexperience, hobbyist AUVs can rarely compete with commercial models on operational depth, durability, or sophistication.

A simple AUV can be constructed from a microcontroller, PVC pressure housing, automatic door lock actuator, syringes, and a DPDT relay.

[20] In 2022–23, during the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Ukrainian armed forces made a number of advancements in uncrewed surface vessel (USV) technology using autonomous control architecture, sometimes with mid-mission telerobotic updates.

There are around 10 companies that sell AUVs on the international market, including Kongsberg Maritime, HII (formerly Hydroid, and previously owned by Kongsberg Maritime)[31]), Bluefin Robotics, Teledyne Gavia (previously known as Hafmynd), International Submarine Engineering (ISE) Ltd, Atlas Elektronik, RTsys,[32] MSubs[33] and OceanScan.

These either optimise the shape according to the operational requirements (Sabretooth) or to benefit from low drag hydrodynamic performance (HUGIN Edge).

The current state of the art is a vehicle that collects, processes and acts on the data it has acquired without operator input.

Although most are currently in their experimental stages, these biomimetic (or bionic) vehicles are able to achieve higher degrees of efficiency in propulsion and maneuverability by copying successful designs in nature.

A demonstration at Monterey Bay, in California, in September 2006, showed that a 21-inch-diameter (530 mm) AUV can tow a 400-foot-long (120 m) hydrophone array while maintaining a 6-knot (11 km/h) cruising speed.

To improve estimation of its position, and reduce errors in dead reckoning (which grow over time), the AUV can also surface and take its own GPS fix.

[38] Because of their low speed and low-power electronics, the energy required to cycle trim states is far less than for regular AUVs, and gliders can have endurances of months and transoceanic ranges.

[citation needed] Since radio waves do not propagate well under water, many AUV's incorporate acoustic modems to enable remote command and control.