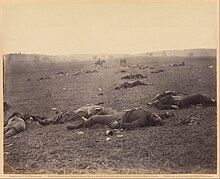

A Harvest of Death

However, when Timothy O'Sullivan photographed the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg, the deadliest engagement of the Civil War, he had recently distanced himself from his sponsor.

The photograph has given rise to a variety of analyses and interpretations, focusing on the realism of the image, the use of staging, and the representation of violence and dead corpses.

Measuring 45.2 × 57.2 cm (17.79 x 22.51 inches), the albumen print (made by Alexander Gardner), from a collodion glass negative (O'Sullivan is the photographer), shows decomposing corpses on the battlefield.

The corpses accumulate in the center of the image, the perspective framed by mist or smoke making it impossible for the viewer to distinguish or count them.

[4] The photograph is accompanied by a lengthy caption, which reads: Slowly, over the misty fields of Gettysburg - as if all reluctant to expose their ghastly horrors to the light - came the sunless morn, after the retreat by Lee's broken army.

Hundreds and thousands of torn Union and rebel soldiers - although many of the former were already interred - strewed the now quiet ground, soaked by the rain, which for two days had drenched the country with its fitful showers [...] Such a picture conveys a useful moral: it shows the blank horror and reality of war, in opposition to its pageantry.

O'Sullivan's equipment appears incidentally in the far left of the photograph Confederate dead gathered for burial at the southwestern edge of the Rose woods, on the Gettysburg battlefield.

Northern photographers Alexander Gardner and Timothy O'Sullivan collected for their employer Mathew Brady "conventional subjects, such as encampments populated by officers and infantrymen, towns on the warpath, munitions, ships", but above all dead Union and Confederate soldiers lying on the scorched ground of Gettysburg and Antietam.

[16] For historian John Keegan, landscape and wooded terrain were the main factors behind this excess mortality, "as troops met by surprise, in a context of poor visibility, and found it difficult to disengage because of the dense vegetation.

[11] Thus, "at the outbreak of war, the American photographer's ambition is to record the history of the United States, focusing in particular on the daily lives of those involved in the conflict, from the general to the common soldier: he shows individuals above all, while erasing hierarchies.

[13] For film historian Jérôme Bimbenet, it was probably the private initiative that enabled O'Sullivan's images to be both realistic and innovative - unlike under government commissioned work.

With living subjects, one adopts a pose; with immobile corpses, as Susan Sontag points out, the photographer remains the one who arranges the elements in the image.

Their subject matter appears to be different: "The commentary on the first photograph describes rebel soldiers, who died attacking a patriot army and were abandoned on the battlefield.

[18][19][20] According to historian François Cochet, if "the same corpses are used both to honor Union soldiers who died doing their duty, and to [sic] describe rebels killed while mounting an assault on Northern patriots", it's because, in his view, "the rules of total media warfare were set as early as the American Civil War.

"[21] For Héloïse Conésa, A Harvest of Death bears witness to a pioneering "falsification", as O'Sullivan seeks to "push the tragic dimension of his shooting to the extreme.

[23] For historian François Cochet, this staging raises the question of the place and role of photography, as it shows "a deeply felt relationship with the 'truth', with the conviction, still widely shared, that 'it's true because it's been photographed'.

"[26] The website of the international photojournalism festival Visa pour l'image points to a filiation in the rejection of violence, as Gardner and O'Sullivan "revealed the other side of the heroic decor of war by using photography to describe its dreadful details, publishing the very first images of battlefields strewn with corpses.

[28] For Hélène Puiseux, Director of Studies at the École Pratique des Hautes Études, photographs of the Crimean War, and even more clearly those of the American Civil War, helped redefine the figure of the battle, and she describes its genealogy: "When photography was born, the battle had been inscribed for several centuries both in military reality as a strategic model [...] and in cultural representations.

"[38] While the photographer's observation is not entirely voluntary - it is still impossible to capture the moment of combat, and photography provides a kind of post-war record - its impact is no less clear: "Why make war under these conditions?

"[38] Art historian François Robichon points out that, even taking O'Sullivan's staging into account, "if the photograph can be made to lie about its meaning, the corpses are very real, and the sight of them has upset established conventions.

[43] Francis Trevelyan Miller's The photographic history of the Civil War, published in 1911, uses photography as a vehicle for national unity, marked by pacifism.

[46][47][48][49][50] The revelation in 1975 by military historian Frassanito of the staging elements in the photographs attributed to Brady paved the way for a new and popular approach to the historical investigation of old photos.

[22] In 2006, A Harvest of Death thus inspired a work that questions the "nature of the 'image of history' in the contemporary era, by resorting to the industry of simulation: Hollywood."

Starting from the observation that the school textbook is an achronic sum of documents, all presented in a certain immediacy and with a supposedly spontaneous comprehension ("everyone sees and therefore knows, because everyone looks at photo reports every day"), he promotes in the classroom an assumed, controlled anachronistic reading of old photographs, such as A Harvest of Death, the analysis of which would bring out, for pupils, questions useful for reading photo reports of current conflicts.