A Voyage Round the World

During the preparations for Cook's voyage, the expedition's naturalist Joseph Banks had withdrawn his participation, and Georg's father, Johann Reinhold Forster, had taken his place at very short notice, with his seventeen-year-old son as his assistant.

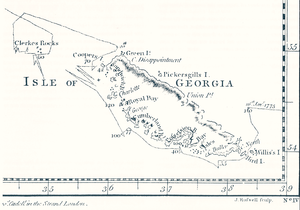

On the voyage, they circumnavigated the world, crossed the Antarctic Circle and sailed as far south as 71° 10′, discovered several Pacific islands, encountered diverse cultures and described many species of plants and animals.

[10] Cook circumnavigated New Zealand, proving it was not attached to a landmass farther south, and mapped the east coast of Australia but had not found evidence for a large southern continent.

In April 1776, Sandwich brokered a compromise that both sides agreed to: Cook would write the first volume, containing a narrative of the journey, the nautical observations, and his own remarks on the natives.

[52][53] Georg used his own notes and recollections,[54] including his own memorandum Observationes historiam naturalem spectantes quas in navigationes ad terras australes institutere coepit G. F. mense Julio, anno MDCCLXXII, which contains botanical and biological observations up to 1 January 1773.

The greatest navigator of his time, two able astronomers, a man of science to study nature in all her recesses, and a painter to copy some of her most curious productions, were selected at the expence of the nation.

He proceeds with an apology for producing a work separate to Cook's, and gives an account of the life in England of Tahitian native Omai, who had arrived in Europe on Adventure in 1774.

Seeing it was impossible to advance farther that way, Captain Cook ordered the ships to put about, and stood north-east by north, after having reached 67° 15′ south latitude, where many whales, snowy, grey, and antarctic petrels, appeared in every quarter.

Some among them, however, submitted with reluctance to this vile prostitution; and, but for the authority and menaces of the men, would not have complied with the desires of a set of people who could, with unconcern, behold their tears and hear their complaints. ...

Encouraged by the lucrative nature of this infamous commerce, the New Zeelanders went through the whole vessel, offering their daughters and sisters promiscuously to every person's embraces, in exchange for our iron tools, which they knew could not be purchased at an easier rate.

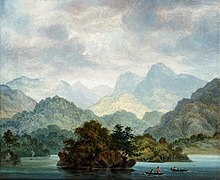

The mountains, clothed with forests, rose majestic in various spiry forms, on which we already perceived the light of the rising sun: nearer to the eye a lower range of hills, easier of ascent, appeared, wooded like the former, and coloured with several pleasing hues of green, soberly mixed with autumnal browns.

A storm hinders them from passing west through Cook's Strait, and they have a terrible night, in which most of the beds are under water and the Forsters hear the curses of the sailors "and not a single reflection bridled their blasphemous tongues".

Forster describes various trades and excursions, and comments on the treatment of women: Among all savage nations the weaker sex is ill-treated, and the law of the strongest is put in force.

[82]A shipmate buys the head of a victim of a recent fight, and takes it on board, where other natives proceed to eat the cheeks, proving the existence of cannibalism in New Zealand.

They take provisions to continue their journey, with the "hope of completing the circle round the South-Pole in a high latitude during the next inhospitable summer, and of returning to England within the space of eight months".

Mahine marries a Tahitian girl, and the ceremony is witnessed by a midshipman, who can not relate any details; Forster laments the lost opportunity to observe the local customs.

Many natives gather on the shore in two groups, but Cook scares them away: One of them, standing close to the water's edge, was so bold as to turn his posteriors towards us, and slap them with his hand, which is the usual challenge with all the nations of the South Sea.

Thus, after escaping innumerable dangers, and suffering a long series of hardships, we happily completed a voyage, which had lasted three years and sixteen days; in the course of which, it is computed we run over a greater space of sea than any ship ever did before us; since, taking all our tracks together, they form more than thrice the circumference of the globe.

[90]While it did not sell well, Voyage was well received critically in Britain, with many favourable reviews,[91] some of which included quotations from both Forster's and Cook's report that demonstrated the superior style of the former.

[96] The reviewer concludes by "acknowledging the pleasure we have received from the perusal of this amusing and well-written journal; which is rendered every where interesting by the pleasing manner in which the Author relates the various incidents of the voyage in general; as well as those which occurred to himself, in particular, during his several botanical excursions into the country".

[99] James Boswell spoke favourably of the book, while Samuel Johnson was less impressed: I talked to him of Forster's Voyage to the South Seas, which pleased me; but I found he did not like it.

[102] Wales, who had quarrelled with Reinhold on the voyage, later published what the editor of Cook's journals, John Beaglehole called "an octavo pamphlet of 110 indignant pages"[103] attacking the Forsters.

[62] Kahn calls the book a "family enterprise" and a joint work based on Reinhold's journals, stating "probably sixty percent of it was finally written by George".

"[119] Philip Edwards, while pointing out many observations that clearly are Georg's, calls Voyage a "collaborative, consensual work; a single author has been created out of the two minds involved in the composition".

[123] After publication of the German edition, excerpts of which were published in Wieland's influential journal Der Teutsche Merkur, both Forsters became famous, especially Georg, who was celebrated upon his arrival in Germany.

[139] There has been a large body of literature studying Voyage since the 1950s,[140] including the PhD thesis of Ruth Dawson,[141] which contains the most extensive account of the genesis of the text.

[143] Despite making up less than five per cent of the text, almost half of the literature about Voyage has focused exclusively on this part of the journey, often studying Forster's comparisons of European and Tahitian culture and of civilisation and nature.

In his review of it, the anthropologist John Barker praises both Forster's "marvelous narrative" and the editors and ends "... modern scholars, Pacific islanders and casual readers alike are greatly in their debt for bringing this wonderful text out of the archives and making it available in this beautifully produced edition".

[148] The historian Kay Saunders notes the "ethnographic sophistication that was in many respects remarkably free of contemporary Eurocentrism", and praises the editors, stating "commentary over such a vast range of disciplines that defy modern scholarly practice requires an extraordinary degree of competency".

[151] The anthropologist Roger Neich, calling the edition "magnificent", comments that the "narrative initiated a stage in the evolution of travel writing as a literary genre, representing an insightful empiricism and empathy showing that the 'Noble Savage' was not a complete description".