Abbasid architecture

As a result there was a corresponding displacement of the influence of classical and Byzantine artistic and cultural standards in favor of local Mesopotamian models as well as Persian.

The early caliphate's great power and unity allowed architectural features and innovations, such as minarets and carved stucco motifs, to spread quickly across the vast territories under its control.

[6][3] While the Abbasids lost control of large parts of their empire after 870, their architecture continued to be copied by successor states in Iraq, Iran, Egypt and North Africa.

[4] Later Abbasid caliphs were confined to Baghdad and were less involved in public architectural patronage, which was instead dominated by the Seljuks and other rulers who held de facto political power.

[12] During the Umayyad period, Muslims had largely re-used pre-Islamic buildings in the cities they conquered, but by the Abbasid era many of these structures required replacement.

Under the Abbasids, new constructions included not only larger mosques and palaces, but also fortifications, new types of houses, commercial buildings and even recreational facilities for racing and polo matches.

The Abbasids began to lose control over the outlying parts of the empire, with local dynasties gaining effective independence in Khorasan (Samanids) in eastern Iran, Egypt (Tulunids) and Ifriqiya (Aghlabids).

In 945 the Buyids, followers of Shia Islam, became effective rulers as amirs, while the Abbasid caliphs retained their nominal title.

[14] With the long reign of Caliph al-Nasir (r. 1180–1225), coinciding with the Seljuk decline and other factors, the Abbasids once again gained control of Iraq and enjoyed a limited revival.

[3] The destruction wrought by this conflict, along with the relative fragility of building materials vulnerable to environmental damage and the later changes to the city's structure, has contributed to the loss of most of Abbasid-era Baghdad's architecture, with few exceptions.

[13] The design of central courtyards, a hallmark of Assyrian architecture, was integrated into Abbasid buildings, reflecting continuity in spatial organization.

[20] It may represent a deliberate attempt to make an abstract form of decoration that avoids depiction of living things, and this may explain its rapid adoption throughout the Muslim world.

[13] The flatness and openness of the land also made it possible to build on an unprecedentedly vast scale, which the early caliphs frequently did, as exemplified by the new administrative capitals they created.

[33][35] At the foot of the staircase was a large rectangular water basin from which a canal led down to a raised pavilion near the river, 300 meters away from the gate.

[33][35] The eastern courtyard beyond this was a vast esplanade measuring 350 by 180 metres (1,150 by 590 ft) which had water channels, fountains, and possibly gardens.

[38]The Abbasids continued to follow the Umayyad rectangular hypostyle plan with arcaded courtyard (sahn) and covered prayer hall.

They built mosques on a monumental scale using brick construction, stucco ornament and architectural forms developed in Mesopotamia and other regions to the east.

It has a nearly square floor plan with a vast interior courtyard surrounded by roofed spaces with rectangular piers and pointed arches.

The 10th-century the Friday Mosque of Nā'īn (also spelled Nain or Nayin), for its part, preserves some of the best Abbasid stucco decoration of its time, covering its pillars, arches, and mihrab.

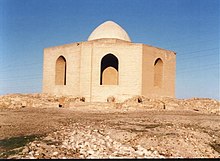

[38] The oldest surviving example of a domed tomb in Islamic architecture is the Qubbat al-Sulaibiyya in Samarra, present-day Iraq, dating from the mid-9th century (c.

[64] In the early 10th century the Abbasids also built another grand mausoleum for their dynasty on the east bank of the Tigris River in Baghdad, but it was later destroyed.

[citation needed] The Nilometer at Fustat, near modern Cairo, built in 861, has elaborate and ornate stonework and discharging arches.

They were less involved in public architectural patronage, which became instead dominated by the Seljuks and other rulers who formally declared loyalty to them but held de facto political power.

[10] It followed the four-iwan plan common in contemporary Iranian architecture, but it had an unusually elongated form, possibly imposed by the narrow urban site.

[78][79] The decoration above the inner gateway of Bab al-Wastani is still partly preserved and consists of a geometric 12-pointed star pattern superimposed over an arabesque background.

The only potential Abbasid palace structure left in Baghdad is located in the al-Maidan neighborhood overlooking the Tigris, in what was formerly the citadel of the city.

[80][81] Popularly known as the "Abbasid Palace", the origins and nature of the structure have been debated by scholars, as there are no surviving inscriptions or texts that identify its name or function.

[85][86] Another scholar, Yasser Tabbaa, has argued that the building lacks some key features of a madrasa and therefore its identification as a palace remains more plausible.

[81] He notes that some historical sources mention the construction of the Dar al-Masnat ("House by the Breakwater") begun by al-Nasir around this location towards 1184, which could therefore correspond to this structure.

[81] Significant parts of the building were reconstructed in the 20th century by the State Establishment of Antiquities and Heritage, including restoration of the great iwan and the adjacent facades.