Abbot

This innovation was not introduced without a struggle, ecclesiastical dignity being regarded as inconsistent with the higher spiritual life, but, before the close of the 5th century, at least in the East, abbots seem almost universally to have become deacons, if not priests.

[3] The second Council of Nicaea, AD 787, recognized the right of abbots to ordain their monks to the inferior orders[3] below the diaconate, a power usually reserved to bishops.

These exceptions, introduced with a good object, had grown into a widespread evil by the 12th century, virtually creating an imperium in imperio, and depriving the bishop of all authority over the chief centres of influence in his diocese.

[3] It has been maintained that the right to wear mitres was sometimes granted by the popes to abbots before the 11th century, but the documents on which this claim is based are not genuine (J. Braun, Liturgische Gewandung, p. 453).

The first undoubted instance is the bull by which Alexander II in 1063 granted the use of the mitre to Egelsinus, abbot of the monastery of St Augustine at Canterbury.

[5] Elsewhere, the mitred abbots that sat in the Estates of Scotland were of Arbroath, Cambuskenneth, Coupar Angus, Dunfermline, Holyrood, Iona, Kelso, Kilwinning, Kinloss, Lindores, Paisley, Melrose, Scone, St Andrews Priory and Sweetheart.

[6] To distinguish abbots from bishops, it was ordained that their mitre should be made of less costly materials, and should not be ornamented with gold, a rule which was soon entirely disregarded, and that the crook of their pastoral staff (the crosier) should turn inwards instead of outwards, indicating that their jurisdiction was limited to their own house.

In abbeys exempt from the archbishop's diocesan jurisdiction, the confirmation and benediction had to be conferred by the pope in person, the house being taxed with the expenses of the new abbot's journey to Rome.

The election was for life, unless the abbot was canonically deprived by the chiefs of his order, or when he was directly subject to them, by the pope or the bishop, and also in England it was for a term of 8–12 years.

The newly elected abbot was to put off his shoes at the door of the church, and proceed barefoot to meet the members of the house advancing in a procession.

Because this permission opened the door to luxurious living, Synods of Aachen decreed that the abbot should dine in the refectory, and be content with the ordinary fare of the monks, unless he had to entertain a guest.

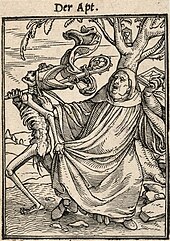

These ordinances proved, however, generally ineffective to secure strictness of diet, and contemporaneous literature abounds with satirical remarks and complaints concerning the inordinate extravagance of the tables of the abbots.

When abbots dined in their own private hall, the Rule of St Benedict charged them to invite their monks to their table, provided there was room, on which occasions the guests were to abstain from quarrels, slanderous talk and idle gossiping.

But by the 10th century the rule was commonly set aside, and we find frequent complaints of abbots dressing in silk, and adopting sumptuous attire.

They rode on mules with gilded bridles, rich saddles and housings, carrying hawks on their wrist, followed by an immense train of attendants.

For instance, we read of Richard Whiting, the last abbot of Glastonbury, judicially murdered by Henry VIII, that his house was a kind of well-ordered court, where as many as 300 sons of noblemen and gentlemen, who had been sent to him for virtuous education, had been brought up, besides others of a lesser rank, whom he fitted for the universities.

The practice of commendation, by which—to meet a contemporary emergency—the revenues of the community were handed over to a lay lord, in return for his protection, early suggested to the emperors and kings the expedient of rewarding their warriors with rich abbeys held in commendam.

[3] During the Carolingian epoch, the custom grew up of granting these as regular heritable fiefs or benefices, and by the 10th century, before the great Cluniac reform, the system was firmly established.

John, patriarch of Antioch at the beginning of the 12th century, informs us that in his time most monasteries had been handed over to laymen, beneficiarii, for life, or for part of their lives, by the emperors.

abate), as commonly used in the Catholic Church on the European continent, is the equivalent of the English "Father" (parallel etymology), being loosely applied to all who have received the tonsure.

The connection many of them had with the church was of the slenderest kind, consisting mainly in adopting the title of abbé, after a remarkably moderate course of theological study, practising celibacy and wearing distinctive dress, a short dark-violet coat with narrow collar.

Being men of presumed learning and undoubted leisure, many of the class found admission to the houses of the French nobility as tutors or advisers.

The class did not survive the Revolution; but the courtesy title of abbé, having long lost all connection in people's minds with any special ecclesiastical function, remained as a convenient general term applicable to any clergyman.

In the East[clarification needed], the principle set forth in the Corpus Juris Civilis still applies, whereby most abbots are immediately subject to the local bishop.

Since the time of Catherine II the ranks of Abbot and Archimandrite have been given as honorary titles in the Russian Church, and may be given to any monastic, even if he does not in fact serve as the superior of a monastery.

The abbot of Loccum, who still carries a pastoral staff, takes precedence over all the clergy of Hanover, and was ex officio a member of the consistory of the kingdom.

In the Church of England, the Bishop of Norwich, by royal decree given by Henry VIII, also holds the honorary title of "Abbot of St.

This title hails back to England's separation from the See of Rome, when King Henry, as supreme head of the newly independent church, took over all of the monasteries, mainly for their possessions, except for St. Benet, which he spared because the abbot and his monks possessed no wealth, and lived like simple beggars, deposing the incumbent Bishop of Norwich and seating the abbot in his place, thus the dual title still held to this day.

The lives of numerous abbots make up a significant contribution to Christian hagiography, one of the most well-known being the Life of St. Benedict of Nursia by St. Gregory the Great.

Saint Joseph, Abbot of Volokolamsk, Russia (1439–1515), wrote a number of influential works against heresy, and about monastic and liturgical discipline, and Christian philanthropy.