Abraham

Abraham purchases a tomb (the Cave of the Patriarchs) at Hebron to be Sarah's grave, thus establishing his right to the land; and, in the second generation, his heir Isaac is married to a woman from his own kin to earn his parents' approval.

[11][12] It is largely concluded that the Torah, the series of books that includes Genesis, was composed during the early Persian period, c. 500 BC, as a result of tensions between Jewish landowners who had stayed in Judah during the Babylonian captivity and traced their right to the land through their "father Abraham", and the returning exiles who based their counterclaim on Moses and the Exodus tradition of the Israelites.

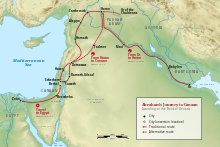

Abram was 75 years old when he left Haran with his wife Sarai, his nephew Lot, and their possessions and people that they had acquired, and traveled to Shechem in Canaan.

[21] When they lived for a while in the Negev after being banished from Egypt and came back to the Bethel and Ai area, Abram's and Lot's sizable herds occupied the same pastures.

[23] During the rebellion of the Jordan River cities, Sodom and Gomorrah, against Elam, Abram's nephew, Lot, was taken prisoner along with his entire household by the invading Elamite forces.

When they caught up with them at Dan, Abram devised a battle plan by splitting his group into more than one unit, and launched a night raid.

They walked over to the peak that overlooked the 'cities of the plain' to discuss the fate of Sodom and Gomorrah for their detestable sins that were so great, it moved God to action.

They rejected that notion and sought to break down Lot's door to get to his male guests,[39] thus confirming the wickedness of the city and portending their imminent destruction.

[44] After living for some time in the land of the Philistines, Abimelech and Phicol, the chief of his troops, approached Abraham because of a dispute that resulted in a violent confrontation at a well.

After Abimelech and Phicol headed back to Philistia, Abraham planted a tamarisk grove in Beersheba and called upon "the name of the LORD, the everlasting God.

[54] After the death of Sarah, Abraham took another wife, a concubine named Keturah, by whom he had six sons: Zimran, Jokshan, Medan, Midian, Ishbak, and Shuah.

Van Seters examined the patriarchal stories and argued that their names, social milieu, and messages strongly suggested that they were Iron Age creations.

[66] Van Seters' and Thompson's works were a paradigm shift in biblical scholarship and archaeology, which gradually led scholars to no longer consider the patriarchal narratives as historical.

[68][69] By the beginning of the 21st century, archaeologists had stopped trying to recover any context that would make Abraham, Isaac or Jacob credible historical figures.

[77] The first, called Persian Imperial authorisation, is that the post-Exilic community devised the Torah as a legal basis on which to function within the Persian Imperial system; the second is that the Pentateuch was written to provide the criteria for determining who would belong to the post-Exilic Jewish community and to establish the power structures and relative positions of its various groups, notably the priesthood and the lay "elders".

[77] The completion of the Torah and its elevation to the centre of post-Exilic Judaism was as much or more about combining older texts as writing new ones – the final Pentateuch was based on existing traditions.

[83] Likewise, some scholars like Daniel E. Fleming and Alice Mandell have argued that the biblical portrayal of the Patriarchs' lifestyle appears to reflect the Amorite culture of the 2nd millennium BCE as attested in texts from the ancient city-state of Mari, suggesting that the Genesis stories retain historical memories of the ancestral origins of some of the Israelites.

In Christianity, Paul the Apostle taught that Abraham's faith in God—preceding the Mosaic law—made him the prototype of all believers, Jewish or gentile; and in Islam, he is seen as a link in the chain of prophets that begins with Adam and culminates in Muhammad.

Before leaving his father's land, Abraham was miraculously saved from the fiery furnace of Nimrod following his brave action of breaking the idols of the Chaldeans into pieces.

[107] In the introduction to his 15th-century translation of the Golden Legend's account of Abraham, William Caxton noted that this patriarch's life was read in church on Quinquagesima Sunday.

A popular hymn sung in many English-speaking Sunday Schools by children is known as "Father Abraham" and emphasizes the patriarch as the spiritual progenitor of Christians.

Islam regards Ibrahim (Abraham) as a link in the chain of prophets that begins with Adam and culminates in Muhammad via Ismail (Ishmael).

[118][119][120] The Druze regard Abraham as the third spokesman (natiq) after Adam and Noah, who helped transmit the foundational teachings of monotheism (tawhid) intended for the larger audience.

[121][122] In Mandaeism, Abraham (Classical Mandaic: ࡀࡁࡓࡀࡄࡉࡌ, romanized: Abrahim) is mentioned in Book 18 of the Right Ginza as the patriarch of the Jewish people.

[133] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá also suggested the "holy manifestations who have been the sources or founders of the various religious systems" were united and agreed in purpose and teaching, and the Abraham, Moses, Zoroaster, the Buddha, Jesus, Muhammad, the Báb and Bahá'u'lláh are one in "spirit and reality".

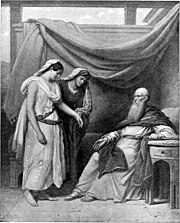

[134] Paintings on the life of Abraham tend to focus on only a few incidents: the sacrifice of Isaac; meeting Melchizedek; entertaining the three angels; Hagar in the desert; and a few others.

[f] Additionally, Martin O'Kane, a professor of Biblical Studies, writes that the parable of Lazarus resting in the "Bosom of Abraham", as described in the Gospel of Luke, became an iconic image in Christian works.

George Segal created figural sculptures by molding plastered gauze strips over live models in his 1987 work Abraham's Farewell to Ishmael.

Thus in Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome, a 5th-century mosaic portrays only the visitors against a gold ground and puts semitransparent copies of them in the "heavenly" space above the scene.

Fear and Trembling (original Danish title: Frygt og Bæven) is an influential philosophical work by Søren Kierkegaard, published in 1843 under the pseudonym Johannes de silentio (John the Silent).