Acanthocephala

Acanthocephalans have complex life cycles, involving at least two hosts, which may include invertebrates, fish, amphibians, birds, and mammals.

[10] This unified taxon is sometimes known as Syndermata, or simply as Rotifera, with the acanthocephalans described as a subclass of a rotifer class Hemirotatoria.

[11] The earliest recognisable description of Acanthocephala – a worm with a proboscis armed with hooks – was made by Italian author Francesco Redi (1684).

The oldest known remains of acanthocephalans are eggs found in a coprolite from the Late Cretaceous Bauru Group of Brazil, around 70–80 million years old, likely from a crocodyliform.

[12] Acanthocephalans are highly adapted to a parasitic mode of life, and have lost many organs and structures through evolutionary processes.

The acanthocephalans lack an excretory system, although some species have been shown to possess flame cells (protonephridia).

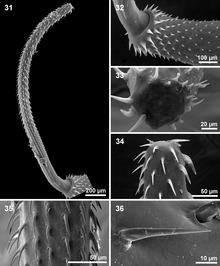

The proboscis is used to pierce the gut wall of the final host, and hold the parasite fast while it completes its life cycle.

[17] The size of these animals varies greatly, ranging from a few millimetres in length to Macracanthorhynchus hirudinaceus, which measures from 10 to 65 centimetres (3.9 to 25.6 in).

Externally, the skin has a thin tegument covering the epidermis, which consists of a syncytium with no cell walls.

Each consists of a prolongation of the syncytial material of the proboscis skin, penetrated by canals and sheathed with a muscular coat.

Acanthocephalans have complex life cycles, involving a number of hosts, for both developmental and resting stages.

The male also possesses three pairs of cement glands, found behind the testes, which pour their secretions through a duct into the vasa deferentia.

From the ovaries, masses of ova dehisce into the body cavity, floating in its fluids for fertilization by male's sperm.

For development to occur, the egg, containing the acanthor, needs to be ingested by an arthropod, usually a crustacean (there is one known life cycle which uses a mollusc as a first intermediate host).

It then penetrates the gut wall, moves into the body cavity, encysts, and begins transformation into the infective cystacanth stage.

When consumed by a suitable final host, the cycstacant excysts, everts its proboscis and pierces the gut wall.

The male uses the excretions of its cement glands to plug the vagina of the female, preventing subsequent matings from occurring.

Thorny-headed worms begin their life cycle inside invertebrates that reside in marine or freshwater systems.

Gammarus lacustris, a small crustacean that inhabits ponds and rivers, is one invertebrate that P. paradoxus may occupy; ducks are one of the definitive hosts.

[18] Second, an infected organism will even go so far as to find a rock or a plant on the surface, clamp its mouth down, and latch on, making it easy prey for the duck.

[18] Finally, infection reduces the pigment distribution and amount in G. lacustris, causing the host to turn blue; unlike their normal brown colour, this makes the crustacean stand out and increases the chance the duck will see it.

Heavy infections of up to 750 parasites per bird are common, causing ulceration to the gut, disease and seasonal mortality.

[23] Acanthocephalosis, a disease caused by Acanthacephalus infection, is prevalent in aquaculture, occurring in Atlantic salmon, rainbow and brown trout, tilapia, and tambaqui.

The reason for this was discovered by Schneider in 1871 when he found that an intermediate host, the scarabaeid beetle grub, was commonly eaten raw.