Accretion (astrophysics)

As the Universe continued to expand and cool, the atoms lost enough kinetic energy, and dark matter coalesced sufficiently, to form protogalaxies.

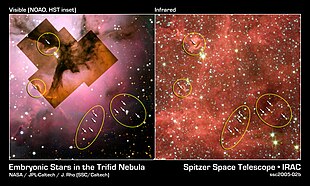

[9] The cores range in mass from a fraction to several times that of the Sun and are called protostellar (protosolar) nebulae.

[8] As the collapse continues, conservation of angular momentum dictates that the rotation of the infalling envelope accelerates, which eventually forms a disk.

As the infall of material from the disk continues, the envelope eventually becomes thin and transparent and the young stellar object (YSO) becomes observable, initially in far-infrared light and later in the visible.

[11] At the next stage, the envelope completely disappears, having been gathered up by the disk, and the protostar becomes a classical T Tauri star.

[16] The emission lines actually form as the accreted gas hits the "surface" of the star, which happens around its magnetic poles.

Accretion disks are common around smaller stars, stellar remnants in a close binary, or black holes surrounded by material (such as those at the centers of galaxies).

[19] However, planetesimal formation in the centimeter-to-meter range is not well understood, and no convincing explanation is offered as to why such grains would accumulate rather than simply rebound.

[24] Or, the particles may take an active role in their concentration via a feedback mechanism referred to as a streaming instability.

The low density of these objects allows them to remain strongly coupled with the gas, thereby avoiding high velocity collisions which could result in their erosion or fragmentation.

Collisions and gravitational interactions between planetesimals combine to produce Moon-size planetary embryos (protoplanets) over roughly 0.1–1 million years.

Pebble accretion is aided by the gas drag felt by objects as they accelerate toward a massive body.

Gas drag slows the pebbles below the escape velocity of the massive body causing them to spiral toward and to be accreted by it.

[28][29] However, core growth via pebble accretion appears incompatible with the final masses and compositions of Uranus and Neptune.

However, Jovian planets began as large, icy planetesimals, which then captured hydrogen and helium gas from the solar nebula.

[35] Also, impacts controlled the formation and destruction of asteroids, and are thought to be a major factor in their geological evolution.

[35] Comets, or their precursors, formed in the outer Solar System, possibly millions of years before planet formation.

Three-dimensional computer simulations indicate the major structural features observed on cometary nuclei can be explained by pairwise low velocity accretion of weak cometesimals.

[38][39] The currently favored formation mechanism is that of the nebular hypothesis, which states that comets are probably a remnant of the original planetesimal "building blocks" from which the planets grew.

[43] The scattered disk was created when Neptune migrated outward into the proto-Kuiper belt, which at the time was much closer to the Sun, and left in its wake a population of dynamically stable objects that could never be affected by its orbit (the Kuiper belt proper), and a population whose perihelia are close enough that Neptune can still disturb them as it travels around the Sun (the scattered disk).

[43] The classic Oort cloud theory states that the Oort cloud, a sphere measuring about 50,000 AU (0.24 pc) in radius, formed at the same time as the solar nebula and occasionally releases comets into the inner Solar System as a giant planet or star passes nearby and causes gravitational disruptions.

[45] The Rosetta mission to comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko determined in 2015 that when Sun's heat penetrates the surface, it triggers evaporation (sublimation) of buried ice.