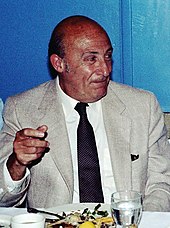

Art Spiegelman

[3] Spiegelman began his career with Topps (a bubblegum and trading card company) in the mid-1960s, which was his main financial support for two decades; there he co-created parodic series such as Wacky Packages in the 1960s and Garbage Pail Kids in the 1980s.

A selection of these strips appeared in the collection Breakdowns in 1977, after which Spiegelman turned focus to the book-length Maus, about his relationship with his father, a Holocaust survivor.

The postmodern book depicts Germans as cats, Jews as mice, ethnic Poles as pigs, and citizens of the United States as dogs.

He was earning money from his drawing by the time he reached high school and sold artwork to the original Long Island Press and other outlets.

[12] After he graduated in 1965, Spiegelman's parents urged him to pursue the financial security of a career such as dentistry, but he chose instead to enroll at Harpur College to study art and philosophy.

[17] He spent a month in Binghamton State Mental Hospital, and shortly after he exited it, his mother died by suicide following the death of her only surviving brother.

Some of the comix he produced during this period include The Compleat Mr. Infinity (1970), a ten-page booklet of explicit comic strips, and The Viper Vicar of Vice, Villainy and Vickedness (1972),[19] a transgressive work in the vein of fellow underground cartoonist S. Clay Wilson.

[12] Seeing Green's revealingly autobiographical Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary while in-progress in 1971 inspired Spiegelman to produce "Prisoner on the Hell Planet", an expressionistic work that dealt with his mother's suicide; it appeared in 1973[25][26] in Short Order Comix #1,[27] which he edited.

"[29] The often-reprinted[30] "Ace Hole, Midget Detective" of 1974 was a Cubist-style nonlinear parody of hardboiled crime fiction full of non sequiturs.

It stood out from similar publications by having an editorial plan, in which Spiegelman and Griffith attempt to show how comics connect to the broader realms of artistic and literary culture.

[34] Arcade also introduced art from ages past, as well as contemporary literary pieces by writers such as William S. Burroughs and Charles Bukowski.

[35] In 1975, Spiegelman moved back to New York City,[36] which put most of the editorial work for Arcade on the shoulders of Griffith and his cartoonist wife, Diane Noomin.

[45] While it included work from such established underground cartoonists as Crumb and Griffith,[37] Raw focused on publishing artists who were virtually unknown, avant-garde cartoonists such as Charles Burns, Lynda Barry, Chris Ware, Ben Katchor, and Gary Panter, and introduced English-speaking audiences to translations of foreign works by José Muñoz, Chéri Samba, Joost Swarte, Yoshiharu Tsuge,[28] Jacques Tardi, and others.

[36] Spiegelman learned in 1985 that Steven Spielberg was producing an animated film about Jewish mice who escape persecution in Eastern Europe by fleeing to the United States.

[51] He struggled to find a publisher[8] until in 1986, after the publication in The New York Times of a rave review of the work-in-progress, Pantheon agreed to release a collection of the first six chapters.

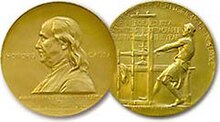

[55] Maus attracted an unprecedented amount of critical attention for a work of comics, including an exhibition at New York's Museum of Modern Art[59] and a special Pulitzer Prize in 1992.

His first cover appeared on the February 15, 1993, Valentine's Day issue and showed a black West Indian woman and a Hasidic man kissing.

[64][65] Within The New Yorker's pages, Spiegelman contributed strips such as a collaboration, "In the Dumps", with children's illustrator Maurice Sendak[66][67] and an obituary to Charles M. Schulz, "Abstract Thought is a Warm Puppy".

[80] Nevertheless, Spiegelman asserted he left not over political differences, as had been widely reported,[81] but because The New Yorker was not interested in doing serialized work,[81] which he wanted to do with his next project.

An internal memo advised Indigo staff to tell people: "the decision was made based on the fact that the content about to be published has been known to ignite demonstrations around the world.

[94] Art Spiegelman's Co-Mix: A Retrospective débuted at Angoulême in 2012 and by the end of 2014 had traveled to Paris, Cologne, Vancouver, New York, and Toronto.

The strip, "Notes from a First Amendment Fundamentalist", depicts Muhammad, and Spiegelman believed the rejection was censorship, though the magazine asserted it never intended to run the cartoon.

[102] The documentary covers the role that tragedy has played in inspiring Spiegelman's work, including the Holocaust, his mother's suicide, and the September 11 attacks.

[110] A critic in The New Republic compared Spiegelman's dialogue writing to a young Philip Roth in his ability "to make the Jewish speech of several generations sound fresh and convincing".

[111] Chief among his other early cartooning influences include Will Eisner,[112] John Stanley's version of Little Lulu, Winsor McCay's Little Nemo, George Herriman's Krazy Kat,[111] and Bernard Krigstein's short strip "Master Race [fr]".

[114] Spiegelman acknowledges Franz Kafka as an early influence,[115] whom he says he has read since the age of 12,[116] and lists Vladimir Nabokov, William Faulkner, and Gertrude Stein among the writers whose work "stayed with" him.

[36] As co-editor of Raw, he helped propel the careers of younger cartoonists whom he mentored, such as Chris Ware,[82] and published the work of his School of Visual Arts students, such as Kaz, Drew Friedman, and Mark Newgarden.

[81] He told Peanuts creator Charles Schulz he was not religious, but identified with the "alienated diaspora culture of Kafka and Freud ... what Stalin pejoratively called rootless cosmopolitanism".

[124] Spiegelman's belief that comics are best expressed in a diagrammatic or iconic manner has had a particular influence on formalists such as Chris Ware and his former student Scott McCloud.

Spiegelman played himself in the 2007 episode "Husbands and Knives" of the animated television series The Simpsons with fellow comics creators Daniel Clowes and Alan Moore.