Acritarch

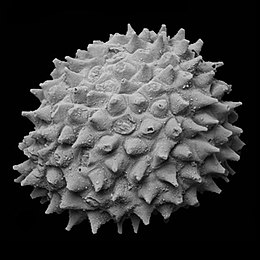

Acritarchs were originally defined as non-acid soluble (i.e. non-carbonate, non-siliceous) organic-walled microfossils consisting of a central cavity, and whose biological affinities cannot be determined with certainty.

[citation needed] The informal group, Acritarcha Evitt 1963, was originally divided into the Subgroups: Acanthomorphitae, Polygonomorphitae, Prismatomorphitae, Oömorphitae, Netromorphitae, Dinetromorphitae, Stephanomorphitae, Pteromorphitae, Herkomorphitae, Platymorphitae, Sphaeromorphitae, and Disphaeromorphitae.

While archaea and bacteria (prokaryotes) usually produce simple fossils of a very small size, eukaryotic unicellular fossils are usually larger and more complex, with external morphological projections and ornamentation such as spines and hairs that only eukaryotes can produce; as most acritarchs have external projections (e.g., hair, spines, thick cell membranes, etc.

Their populations crashed during periods of extensive worldwide glaciations that covered the majority of the planet, but they proliferated in the Cambrian explosion and reached their highest diversity in the Paleozoic.

Approximately 1,000 million years ago, species longevity fell sharply, suggesting that predation pressure, probably by protist herbivores, became an important factor.

Predation would have kept populations in check, meaning that some nutrients were left unused, and new niches were available for new species to occupy.