Action film

Following the September 11 attacks, a return to the early forms of the genre appeared in the wake of Kill Bill and The Expendables films.

"[3] O'Brien wrote further in his book Action Movies: The Cinema of Striking Back to suggest action films being unique and not just a series of action sequences, stating that that was the difference between Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) and Die Hard (1988), that while both were mainstream Hollywood blockbusters with a hero asserting masculinity and overcoming obstacles to a personal and social solution, John McClane in Die Hard repeatedly firing his automatic pistol while swinging from a high rise was not congruent with the image of Indiana Jones in Raiders swinging his whip to fend off villains in the backstreets of Cairo.

[7] British author and academic Yvonne Tasker expanded on this topic, stating that action films have no clear and constant iconography or settings.

In her book The Hollywood Action and Adventure Film (2015), she found that the most broadly consistent themes tend to be a characters quest from freedom from oppression such as a hero overcoming enemies or obstacles and physical conflicts or challenge, usually battling other humans or alien opponents.

[13] These films came under increasing attack by both government officials and cultural elites for their allegedly superstitious and anarchistic tendencies, leading them to be banned in 1932.

This led to a growing demand in both local and regional markets in the early 1960s and saw a surge in production of Hong Kong martial arts films that went beyond the stories about Wong Fei-hung which were declining in popularity.

[21] A new studio, Golden Harvest quickly became one of independent filmmakers to grant creative freedom and pay and attracted new directors and actors, including Bruce Lee.

[8] The formative films would be from the 1960s to the early 1980s where the Anti-hero appears in cinema, featuring characters who act and transcend the law and social conventions.

This appears initially in films like Bullitt (1968) where a tough police officer protects society by upholding the law against systematic corruption.

[27] The vigilantism reappears in other films that were exploitative of southern society such as Billy Jack (1971) and White Lightning (1973) and "good ol' boy" comedies like Smokey and the Bandit (1977).

The decade continued the trends of formative period with heroes as avengers (Lethal Weapon (1987)), rogue police officers (Die Hard (1988)) and mercenary warriors (Commando (1985)).

[33] The fourth phase arrived following the September 11 attacks in 2001, which suggested an end to fantastical elements that defined the action hero and genre.

O'Brien found that Tarantino's films were post-modern takes on the themes that rescinded irony to restore "cinephile re-actualization of the genre's conventions.

[39] Screenwriter and academic Jule Selbo expanded on this, describing a film as "crime/action" or an "action/crime" or other hybrids was "only a semantic exercise" as both genres are important in the construction phase of the narrative.

James Monaco wrote in 1979 in American Film Now: The People, The Power, The Money, the Movies that "the lines that separate on genre from another have continued to disintegrate.

[45] Stephen Teo wrote in his book on Wuxia that there is no satisfactory English translation of the term, with it often being identified as "the swordplay film" in critical studies.

[48] Its name is derived from the Cantonese term gong fu which has two meanings: the physical effort required to completing a task and the abilities and skills acquired over time.

[47] While heroes in kung fu films often display chivalry, they generally hail from different fighting schools, namely wudang and shaolin.

[61][62] Even internationally popular films like Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) had negligible effects in American productions in either the direct-to-video field, or in similarly low-budget theatrical releases such as Bulletproof Monk (2003).

[64] Heroic Bloodshed is genre a that originates with English-language Hong Kong action and crime film fan communities in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Prompted by the success of Enter the Dragon and the popularity of Bruce Lee, Toei made their own Bruce Lee-style martial arts films, with The Street Fighter and its two sequels starring Sonny Chiba as well as a spin-off with a female lead similar to Hong Kong's Angela Mao called Sister Street Fighter.

[88] Versus grew to become popular outside of Japan, and Kitamura said he was aiming for the foreign audience, as he was disappointed with the current state of Japanese films.

[98] Early Korean heirs to Hong Kong action films include Rules of The Game (1994), Beat (1997), and Green Fish (1997) involving men who gain confidence and achieve personal growth as they embark on journeys to protect national state and meet devastating ends.

[100] Time Out magazine conducted a poll with fifty experts in the field of action cinema, including actors, critics, filmmakers and stuntmen.

[101] In Hong Kong, the "new school" of martial arts films that Shaw Brothers brought in 1965 featured what Yip described as "strong, active female characters as protagonists."

Accusations of these muscular women of the era were levelled at that them by 1993 were that they were "men in drag" and that the films generally have to "explain" why their female leads displayed physical aggression and why they were "driven to do it.

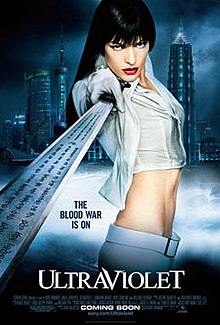

[102] Hypersexualized female action leads had tight fitting or revealing costumes that Tasker identified as "exaggerated statements of sexuality" and in the tradition of "fetishistic figure of fantasy" derives from comic books and soft pornography.

[107] While characters like Frank in The Transporter series are permitted to visibly sweat, strain and be bloodied, Purse found a reluctance for filmmakers to have their female leads have any appearance warping injuries to ensure a perfectly made-up face.

[108] Comedy is often used in films of this period to place the female leads in implausible elements, such as in Charlie's Angels, Fantastic Four (2005) and My Super Ex-Girlfriend (2006).

[110] Marc O'Day interprets the action heroine's dual status of an active subject and sexual object was overturning the traditional gender binary because the films "assume that women are powerful" without resorting to justify her physical aggression through narratives involving maternal drive, mental instability or trauma.