Administration of territory in dynastic China

During the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC), they were coordinated by commanderies (jun) and expanded throughout the entire empire, but the Han (202 BC–220 AD) returned them to indirect rule by vassals.

[1] The county was headed by a "court-appointed official" (chaoting mingguan) responsible for collecting taxes, hearing trials, public order, education, examinations, morality, and religious customs.

Each circuit (dao or lu) was assigned four Commissions, each tasked with a different administrative activity: military, fiscal, judicial, and supply.

[3] The Yuan province, called a Branch Secretariat (xing zhongshu sheng), was governed by two Managers of Governmental Affairs (pingchang zhengshi).

During the Qing dynasty, the Shuntian prefect was allowed to directly memorialize the emperor, but the subprefectures and counties were jointly governed with the governor of Zhili.

Control of a township was divided between an Elder (sanlao), the moral authority, a Husbander (sefu), who handled fiscal affairs, and a Patroller (youjiao), who kept the local peace.

The eastern nobility ruled kingdoms (wangguo) or marquisates (houguo) that were largely autonomous until 154 BC when a series of imperial actions gradually brought them under central control.

In 124 BC, Emperor Wu established the Taixue with a faculty of five Erudites (boshi) and student body of 50, recommended by Commandery Governors, that grew to 3,000 by the end of the millennium.

Students studied the classics at the Taixue for one year and then sat a written graduation exam, after which they were either appointed or returned home to seek positions on the commandery staff.

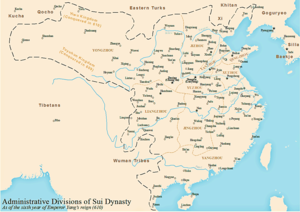

[17] The period of dynastic turmoil between the Han and Sui dynasties led to proliferation of counties, commanderies, and regions, often set up to administer the large refugee populations moving across China.

In the early years of the Sui dynasty, Area Commanders-in-chief (zongguan) ruled as semi-autonomous warlords, but they were gradually replaced with Branch Departments of State Affairs (xing taisheng).

Classicists were tested on the Confucian canon, which was considered an easy task at the time, so those who passed were awarded posts in the lower rungs of officialdom.

Under Emperor Wen, all officials down to the county level had to be appointed by the Department of State Affairs in the capital and were subjected to annual merit rating evaluations.

Aristocratic officials were ranked based on their pedigree with distinctions such as "high expectations", "pure", and "impure" so that they could be awarded offices appropriately.

[22] At the beginning of the Tang dynasty, Emperor Taizong introduced "circuits" to help monitor the operation of prefectures (rather than a new primary level of administration).

[23] The circuit was assigned a Surveillance Commissioner (ancha shi), who functioned as an overall coordinator rather than a governor, and visited prefectures and checked up on the performance of officials.

[21] In 693, Wu Zetian expanded the examination system by allowing commoners and gentry previously disqualified by their non-elite backgrounds to take the tests.

[31]Imperial examinations were only held for the Southern Establishments until the last decade of the dynasty when Khitans found it an acceptable avenue for advancing their careers.

[34] The examinations were opened to adult Chinese males, with some restrictions, including even individuals from the occupied northern territories of the Liao and Jin dynasties.

Chinese officials also faced discrimination, at times physical, while Jurchens retained all final decision-making powers within the Jin government.

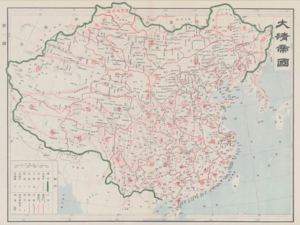

[5] Below the provinces were circuits with agencies headed by Commissioners who coordinated matters between the provincial level authorities and lower-level routes, prefectures, and districts.

A quota system both for number of candidates and degrees awarded was instituted based on the classification of the four groups, those being the Mongols (and Semu), Han, and Manzi, with further restrictions by province favoring the northeast of the empire (Mongolia) and its vicinities.

[49] Officials serving in the capital were nominally supposed to receive merit ratings every 30 months, for demotion or promotion, but in practice government posts were inherited from father to son.

Nominally, they had the same rank as their counterparts in the regular administration system[61] The central government gave more autonomy to those military tusi who controlled areas with fewer Han Chinese people and had underdeveloped infrastructure.

[62] Throughout its 276-year history, the Ming dynasty bestowed a total of 1608 tusi titles, 960 of which were military-rank and 648 were civilian-rank,[63] the majority of which were in Yunnan, Guizhou and Sichuan.

The tusi acted as stop gaps until enough Chinese settlers arrived for a "tipping point" to be reached, and they were then converted into official prefectures and counties to be fully annexed into the central bureaucratic system of the Ming dynasty.

By the time of the Ming-Qing transition, what remained in the southwest were only a few small autonomous polities, and the Rebellion of the Three Feudatories (sanfan zhi luan; 1673–81) did much to erase these from the landscape.

However unlike the Ming tripartite provincial administration, Qing provinces were governed by a single Governor (xunfu) who held substantial power.

There was also an unofficial Provincial Education Commissioner (tidu xuezheng) in every province who supervised schools and certified candidates for the civil service examinations.

Many of the Mongols were organized into Manchu-style banners or leagues and it was not until the 19th century that Mongolia was brought under tighter control under a Manchu general or Grand Minister Consultant (canzan dachen) and several Judicial Administrators (banshi siyuan).