LIGO

Initially, two large observatories were built in the United States with the aim of detecting gravitational waves by laser interferometry.

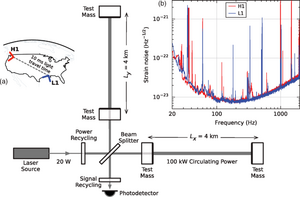

The two LIGO observatories use mirrors spaced four kilometers apart to measure changes in length—over an effective span of 1120 km—of less than one ten-thousandth the charge diameter of a proton.

[2] The initial LIGO observatories were funded by the United States National Science Foundation (NSF) and were conceived, built and are operated by Caltech and MIT.

[11][12] In 2017, the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Rainer Weiss, Kip Thorne and Barry C. Barish "for decisive contributions to the LIGO detector and the observation of gravitational waves".

[21] The LIGO concept built upon early work by many scientists to test a component of Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity, the existence of gravitational waves.

Starting in the 1960s, American scientists including Joseph Weber, as well as Soviet scientists Mikhail Gertsenshtein and Vladislav Pustovoit, conceived of basic ideas and prototypes of laser interferometry,[22][23] and in 1967 Rainer Weiss of MIT published an analysis of interferometer use and initiated the construction of a prototype with military funding, but it was terminated before it could become operational.

[25] In 1980, the NSF funded the study of a large interferometer led by MIT (Paul Linsay, Peter Saulson, Rainer Weiss), and the following year, Caltech constructed a 40-meter prototype (Ronald Drever and Stan Whitcomb).

[42] In mid-September 2015, "the world's largest gravitational-wave facility" completed a five-year US$200-million overhaul, bringing the total cost to $620 million.

[48] On 2 May 2016, members of the LIGO Scientific Collaboration and other contributors were awarded a Special Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics for contributing to the direct detection of gravitational waves.

[53] A fourth detection of a black hole merger, between objects of 30.5 and 25.3 solar masses, was observed on 14 August 2017 and was announced on 27 September 2017.

[54] In 2017, Weiss, Barish, and Thorne received the Nobel Prize in Physics "for decisive contributions to the LIGO detector and the observation of gravitational waves."

[55][56][57] After shutting down for improvements, LIGO resumed operation on 26 March 2019, with Virgo joining the network of gravitational-wave detectors on 1 April 2019.

Their existence was indirectly confirmed when observations of the binary pulsar PSR 1913+16 in 1974 showed an orbital decay which matched Einstein's predictions of energy loss by gravitational radiation.

Joseph Weber pioneered the effort to detect gravitational waves in the 1960s through his work on resonant mass bar detectors.

In 1962, M. E. Gertsenshtein and V. I. Pustovoit published the very first paper describing the principles for using interferometers for the detection of very long wavelength gravitational waves.

He pointed out the 1962 paper and mentioned the possibility of detecting gravitational waves if the interferometric technology and measuring techniques improved.

The observatory may, in theory, also observe more exotic hypothetical phenomena, such as gravitational waves caused by oscillating cosmic strings or colliding domain walls.

Through the use of trilateration, the difference in arrival times helps to determine the source of the wave, especially when a third similar instrument like Virgo, located at an even greater distance in Europe, is added.

During the same era, Hanford retained its original passive seismic isolation system due to limited geologic activity in Southeastern Washington.

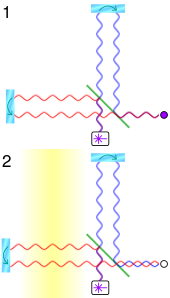

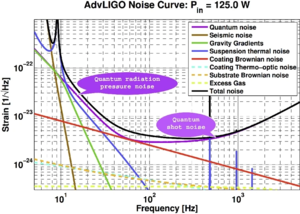

In actual operation, noise sources can cause movement in the optics, producing similar effects to real gravitational wave signals; a great deal of the art and complexity in the instrument is in finding ways to reduce these spurious motions of the mirrors.

[71] Based on current models of astronomical events, and the predictions of the general theory of relativity,[72][73][74] gravitational waves that originate tens of millions of light years from Earth are expected to distort the 4-kilometre (2.5 mi) mirror spacing by about 10−18 m, less than one-thousandth the charge diameter of a proton.

A typical event which might cause a detection event would be the late stage inspiral and merger of two 10-solar-mass black holes, not necessarily located in the Milky Way galaxy, which is expected to result in a very specific sequence of signals often summarized by the slogan chirp, burst, quasi-normal mode ringing, exponential decay.

In their fourth Science Run at the end of 2004, the LIGO detectors demonstrated sensitivities in measuring these displacements to within a factor of two of their design.

During LIGO's fifth Science Run in November 2005, sensitivity reached the primary design specification of a detectable strain of one part in 1021 over a 100 Hz bandwidth.

The baseline inspiral of two roughly solar-mass neutron stars is typically expected to be observable if it occurs within about 8 million parsecs (26×10^6 ly), or the vicinity of the Local Group, averaged over all directions and polarizations.

Also at this time, LIGO and GEO 600 (the German-UK interferometric detector) began a joint science run, during which they collected data for several months.

The expansion of worldwide activities in gravitational-wave detection to produce an effective global network has been a goal of LIGO for many years.

In 2010, a developmental roadmap[97] issued by the Gravitational Wave International Committee (GWIC) recommended that an expansion of the global array of interferometric detectors be pursued as a highest priority.

Thus, all costs required to build a laboratory equivalent to the LIGO sites to house the detector would have to be borne by the host country.

[100] The first potential distant location was at AIGO in Western Australia,[101] however the Australian government was unwilling to commit funding by 1 October 2011 deadline.