Advanced Tactical Fighter

[3] This was motivated by the shift in U.S. military doctrine towards striking the enemy's rear echelon as eventually outlined in the AirLand Battle concept, as well as intelligence reports of multiple emerging worldwide threats emanating from the Soviet Union.

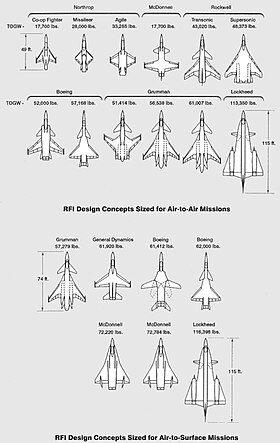

As the ATF was still early in its requirements definition, including whether the aircraft should be focused on air-to-air or air-to-surface, there was great variety in the RFI responses; the submitted designs generally fell into four concepts.

Even with the variety of the submitted designs in the responses, the common areas among some or all the concepts were reduced observability, or stealth (though not to the extent of the final requirements), short takeoff and landing (STOL) and sustained supersonic cruise without afterburners, or supercruise.

[12][13] By October 1983, the ATF Concept Development Team had become the System Program Office (SPO) led by Colonel Albert C. Piccirillo at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base.

[17][18] With the ATF's mission now focused on air-to-air, another round of requests were sent to the industry for concept exploration and study contracts were awarded to seven airframe manufacturers for further definition of their designs.

By late 1984, the SPO had settled on the ATF requirements and released the Statement of Operational Need (SON), which called for a fighter with a takeoff gross weight of 50,000 pounds (23,000 kg), a mission radius of 500 nautical miles (930 km) mixed subsonic/supersonic or 700–800 nautical miles (1,300–1,480 km) subsonic, supercruise speed of Mach 1.4–1.5, the ability to use a 2,000-foot (600 m) runway, and signature reduction particularly in the frontal sector.

[26] At this time, the SPO had anticipated procuring 750 ATFs at a unit cost of $35 million in fiscal year (FY) 1985 dollars (~$84.2 million in 2023) with final design selection in 1989 and service entry in 1995 with a peak production rate of 72 aircraft per year, although even at this point the peak rate was being questioned and the entry date was at risk of slipping to the late 1990s due to potential RFP adjustments and budget constraints.

[29] Because of this late addition due to political pressure, the prototype air vehicles were to be "best-effort" machines not meant to perform a competitive flyoff or represent a production aircraft that meets every requirement, but to demonstrate the viability of its concept and mitigate risk.

[1] Because contractors were expected to make immense investments of their own — likely approaching the amount awarded by the contracts themselves when combined — in order to develop the necessary technology to meet the ambitious requirements, teaming was encouraged by the SPO.

Northrop's proposal leveraged its considerable experience with stealth to produce a refined and well-understood aircraft design that was very similar to the eventual flying prototype.

[37] During Dem/Val, the ATF SPO program manager was Colonel James A. Fain, while the technical director (or chief engineer) was Eric "Rick" Abell.

[36] With the ATF system specification, the SPO had set the technical requirements without specifying the "how"; this was meant to give the contractor teams flexibility in developing the requisite technologies and offer competing methods.

[N 10][49] Noteworthy is the Lockheed team's complete redesign of the entire YF-22's shape and configuration in summer of 1987 due to weight concerns,[24][50] while the YF-23 was a continual refinement of Northrop's concept prior to Dem/Val proposal submission.

Accurate artwork of the prototypes, which had been highly classified due to the stealth shaping, was first officially released in 1990 ahead of their public unveiling; the aforementioned Dem/Val extensions also pushed flight testing from 1989 to 1990.

[54] Following a review of the flight test results and proposals, the Secretary of the Air Force Donald Rice announced the Lockheed team and Pratt & Whitney as the competition winner for full-scale development, or Engineering and Manufacturing Development (EMD), on 23 April 1991; by this time, the 1990 Major Aircraft Review by Defense Secretary Dick Cheney had reduced the planned total ATF buy to 650 aircraft and peak production rate to 48 per year.

[N 14][28][63] The selection decision has been speculated by aviation observers to have involved industrial factors and perception of program management as much as the technical merit of the aircraft designs.

[33] In contrast, Lockheed's program management on the F-117 was lauded for meeting performance and delivering on schedule and within budget, with the aircraft achieving operational success over Panama and during the Gulf War.

[24] While the YF-23 air vehicle was in a higher state of maturity and refinement compared to the YF-22 due to the latter's late redesign and partly as a result had better flight performance, the Lockheed team executed a more aggressive flight test plan with considerably higher number of sorties and hours flown; furthermore, Lockheed chose to execute high-visibility tests such as firing missiles and high angle-of-attack maneuvers that, while not required, improved its perception by the USAF in managing weapons systems risk.

[66] With the overall final F-22 and F-23 designs competitive with each other in technical performance and meeting all requirements, the USAF decision then took into consideration non-technical aspects such as confidence in program management when determining the winner.

The program was scrutinized for its costs and less expensive alternatives such as modernized F-15 or F-16 variants were continually being proposed, even though the USAF considered the F-22 to provide the greatest capability increase against peer adversaries for the investment.