Aerial bombardment and international law

Article 26: The officer in command of an attacking force must, before commencing a bombardment, except in cases of assault, do all in his power to warn the authorities.

It stated: "The Contracting Powers agree to prohibit, for a period extending to the close of the Third Peace Conference, the discharge of projectiles and explosives from balloons or by other new methods of a similar nature.

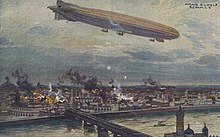

[1] The German bombings of Guernica and Durango in Spain in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939 and the Japanese aerial attacks on crowded Chinese cities during the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937–38 attracted worldwide condemnation, prompting the League of Nations to pass a resolution[16] that called for the protection of civilian populations against bombardment from the air.

[17][18] In response to the resolution passed by the League of Nations,[16] a draft convention in Amsterdam of 1938[19] would have provided specific definitions of what constituted an "undefended" town, excessive civilian casualties and appropriate warning.

This draft convention makes the standard of being undefended quite high – any military units or anti-aircraft within the radius qualifies a town as defended.

Throughout World War II, cities like Chongqing, Warsaw, Rotterdam, London, Coventry, Stalingrad, Hamburg, Dresden, Tokyo, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki suffered aerial bombardment, causing untold numbers of destroyed buildings and the deaths of tens of thousands of civilians.

However, due to the absence of positive or specific customary international humanitarian law prohibiting illegal conducts of aerial warfare in World War II, the indiscriminate bombing of enemy cities was excluded from the category of war crimes at the Nuremberg and Tokyo Trials, therefore, no Axis officers and leaders were prosecuted for authorizing this practice.

Furthermore, the United Nations War Crimes Commission received no notice of records of trial concerning the illegal conduct of air warfare.

[21] Chris Jochnick and Roger Normand in their article The Legitimation of Violence 1: A Critical History of the Laws of War explain that: "By leaving out morale bombing and other attacks on civilians unchallenged, the Tribunal conferred legal legitimacy on such practices.

Colonel Javier Guisández Gómez, at the International Institute of Humanitarian Law in San Remo, points out: In examining these events [Anti-city strategy/blitz] in the light of international humanitarian law, it should be borne in mind that during the Second World War there was no agreement, treaty, convention or any other instrument governing the protection of the civilian population or civilian property, as the Conventions then in force dealt only with the protection of the wounded and the sick on the battlefield and in naval warfare, hospital ships, the laws and customs of war and the protection of prisoners of war.

Permanent Representative to the United Nations (2005–2006)), explained in 2001 why the USA should not adhere to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court: A fair reading of the [Rome Statute], for example, leaves the objective observer unable to answer with confidence whether the United States was guilty of war crimes for its aerial bombing campaigns over Germany and Japan in World War II.

A fortiori, these provisions seem to imply that the United States would have been guilty of a war crime for dropping atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

(Article 51, Para 8)[35] The International Court of Justice gave an advisory opinion in July 1996 on the Legality of the Threat Or Use of Nuclear Weapons.

However, by a split vote, it also found that "[t]he threat or use of nuclear weapons would generally be contrary to the rules of international law applicable in armed conflict."