Strategic bombing during World War II

Britain: China: France: Netherlands: Poland: Soviet Union: United States: Yugoslavia: Germany: Japan: Italy: Hungary: Romania: Bulgaria: Thailand: Asia-Pacific Mediterranean and Middle East Other campaigns Coups World War II (1939–1945) involved sustained strategic bombing of railways, harbours, cities, workers' and civilian housing, and industrial districts in enemy territory.

[48] This means that aerial bombardment of civilian areas in enemy territory by all major belligerents during World War II was not prohibited by positive or specific customary international humanitarian law.

[52] Due to these reasons, the Allies at the Nuremberg and Tokyo Trials never criminalized aerial bombardment of non-combatant targets and Axis leaders who ordered a similar type of practice were not prosecuted.

Chris Jochnick and Roger Normand in their article The Legitimation of Violence 1: A Critical History of the Laws of War explains that: "By leaving out morale bombing and other attacks on civilians unchallenged, the Tribunal conferred legal legitimacy on such practices.

[62] Germany also agreed to abide by Roosevelt's request and explained the bombing of Warsaw as within the agreement because it was supposedly a fortified city—Germany did not have a policy of targeting enemy civilians as part of their doctrine prior to World War II.

"[77] In his book, Augen am Himmel (Eyes on the Sky), Wolfgang Schreyer wrote:[78] Frampol was chosen as an experimental object, because test bombers, flying at low speed, weren't endangered by AA fire.

On 22 September, Wolfram von Richthofen messaged, "Urgently request exploitation of last opportunity for large-scale experiment as devastation terror raid ... Every effort will be made to eradicate Warsaw completely".

By 11 May, the French reported bombs dropped on Henin-Lietard, Bruay, Lens, La Fere, Loan, Nancy, Colmar, Pontoise, Lambersart, Lyons, Bouai, Hasebrouck, Doullens and Abbeville with at least 40 civilians killed.

[109] While Allied light and medium bombers attempted to delay the German invasion by striking at troop columns and bridges, the British War Cabinet gave permission for limited bombing raids against targets such as roads and railways west of the Rhine River.

[119] International news agencies widely reported these figures, portraying Rotterdam as a city mercilessly destroyed by terror bombing without regard for civilian life, with 30,000 dead lying under the ruins.

[124] Churchill explained the rationale of his decision to his French counterparts in a letter dated the 16th: "I have examined today with the War Cabinet and all the experts the request which you made to me last night and this morning for further fighter squadrons.

Many other British cities were hit in the nine-month Blitz, including Plymouth, Swansea, Birmingham, Sheffield, Liverpool, Southampton, Manchester, Bristol, Belfast, Cardiff, Clydebank, Kingston upon Hull and Coventry.

Basil Collier, author of 'The Defence of the United Kingdom', the HMSO's official history, wrote:[157] Although the plan adopted by the Luftwaffe early in September had mentioned attacks on the population of large cities, detailed records of the raids made during the autumn and the winter of 1940–41 do not suggest that indiscriminate bombing of civilians was intended.

The immediate aim, is therefore, twofold, namely, to produce (i) destruction and (ii) fear of death.During the first few months of the area bombing campaign, an internal debate within the British government about the most effective use of the nation's limited resources in waging war on Germany continued.

His calculations (which were questioned at the time, in particular by Professor P. M. S. Blackett of the Admiralty operations research department, expressly refuting Lindemann's conclusions[179]) showed the RAF's Bomber Command would be able to destroy the majority of German houses located in cities quite quickly.

The plan was highly controversial even before it started, but the Cabinet thought that bombing was the only option available to directly attack Germany (as a major invasion of the continent was almost two years away), and the Soviets were demanding that the Western Allies do something to relieve the pressure on the Eastern Front.

Lest there be any confusion, Sir Charles Portal wrote to Air Chief Marshal Norman Bottomley on 15 February,[180] I suppose it is clear that the aiming points will be the built-up areas, and not, for instance, the dockyards or aircraft factories [...].Factories were no longer targets.

[citation needed] The effects of the massive raids using a combination of blockbuster bombs (to blow off roofs) and incendiaries (to start fires in the exposed buildings) created firestorms in some cities.

According to economic historian Adam Tooze, in his book The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy, a turning point in the bomber offensive was reached in March 1943, during the Battle of the Ruhr.

To Harris, his complete success at Hamburg confirmed the validity and necessity of his methods, and he urged that:[183][184] the aim of the Combined Bomber Offensive...should be unambiguously stated [as] the destruction of German cities, the killing of German workers, and the disruption of civilized life throughout Germany.He further said,[185] the destruction of houses, public utilities, transport and lives, the creation of a refugee problem on an unprecedented scale, and the breakdown of morale both at home and at the battle fronts by fear of extended and intensified bombing, are accepted and intended aims of our bombing policy.

With such heavy losses of their primary means of defense against the USAAF's tactics, German planners were forced into a hasty dispersal of industry, with the day fighter arm never being able to fully recover in time.

[11] Most of the losses by Allied airstrikes in the Netherlands were caused by mistakenly bombing the wrong target, initially aiming at German-occupied factories, transportation facilities, population registries, Sicherheitsdienst headquarters, or even German cities at the border.

Sometimes the targets were too small, so the risks of 'collateral damage' were very high, as was shown by the bombing of the Sicherheitsdienst headquarters in Amsterdam and Rotterdam, the station yards of Haarlem, Utrecht, Roosendaal and Leiden, and the bridges in Zutphen and Venlo.

Thirteen B-24 Liberator heavy bombers under the command of Col. Harry A. Halverson from Fayid, Egypt dropped eight bombs into the Black Sea, two onto Constanța, six onto Ploiești, six onto Teișani, and several onto Ciofliceni.

In Dalmatia, the Italian enclave of Zara suffered extensive bombing, which destroyed 60% of the city and killed about 1,000 of its 20,000 inhabitants, prompting most of the population to flee to mainland Italy (the town was later annexed to Yugoslavia).

The main object seems to be to inspire terror by the indiscriminate slaughter of civilians...The Imperial Japanese Navy also carried out a carrier-based airstrike on the armed neutralitarian United States at Pearl Harbor and Oahu on 7 December 1941, resulting in almost 2,500 fatalities and plunging America into World War II the next day.

], even within the Air Force, viewed this as a form of psychological warfare, a significant element in the decision to produce and drop them was the desire to assuage American anxieties about the extent of the destruction created by this new war tactic.

[253] In October 1945, Prince Fumimaro Konoe said the sinking of Japanese vessels by U.S. aircraft combined with the B-29 aerial mining campaign were just as effective as B-29 attacks on industry alone,[254] though he admitted, "the thing that brought about the determination to make peace was the prolonged bombing by the B-29s."

When President Harry S. Truman was briefed on what would happen during an invasion of Japan, he could not afford such a horrendous casualty rate, added to over 400,000 U.S. servicemen who had already died fighting in both the European and Pacific theaters of the war.

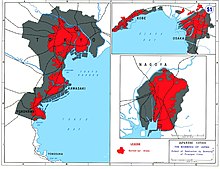

[259] On 9 August, three days later, the B-29 Bockscar flew over the Japanese city of Nagasaki in northwest Kyushu and dropped an implosion-type, plutonium-239 atomic bomb (code-named Fat Man by the U.S.) on it, again accompanied by two other B-29 aircraft for instrumentation and photography.