Aesculapian snake

The Aesculapian snake has been of cultural and historical significance for its role in ancient Greek, Roman and Illyrian mythology and derived symbolism.

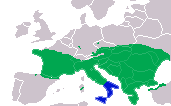

[3][6][7] The contiguous area of the previous nominotypical subspecies, Zamenis longissimus longissimus, which is now the only recognized monotypic form, covers most of France except in the north (up to about the latitude of Paris), the Spanish Pyrenees and the eastern side of the Spanish northern coast, Italy (except the south and Sicily), all of the Balkan peninsula down to Greece and Asia Minor and parts of Central and Eastern Europe up until about the 49th parallel in the eastern part of the range (Switzerland, Austria, South Moravia (Podyjí/Thayatal in Austria) in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, south Poland (mainly Bieszczady/Bukovec Mountains in Slovakia), Romania, south-west Ukraine).

Further isolated populations have been identified in western Germany (Schlangenbad, Odenwald, lower Salzach, plus one - near Passau - connected to the contiguous distribution area) and the northwest of the Czech Republic (near Karlovy Vary, the northernmost known current natural presence of the species).

[6] Also found in a separate enclave south of Greater Caucasus along the Russian, Georgian and Turkish northeastern and eastern shores of the Black Sea.

There are also fossils showing that they had UK residency during earlier interglacial periods but were driven south afterwards with subsequent glacials; these repeated climate-caused contractions and extensions of range in Europe appear to have occurred multiple times over the Pleistocene.

[13] A second, more recently established population was reported in 2010 along Regent's Canal, near the London Zoo, likely living on rats and mice, and thought to number a few dozen.

[17] The Aesculapian snake prefers forested, warm but not hot, moderately humid but not wet, hilly or rocky habitats with proper insolation and varied, not sparse vegetation that provides sufficient variation in local microclimates, helping the reptile with thermoregulation.

The synanthropic aspect appears to be more pronounced in northernmost parts of the range where they are dependent on human structures for food, warmth and hatching grounds.

Predators include badgers and other mustelids, foxes, wild boar (mainly by digging up and decimating hatches and newborns), hedgehogs, and various birds of prey (though there are reports of adults successfully standing their ground against feathered attackers).

Also a threat mainly to juveniles and hatches are domestic animals such as cats, dogs, and chickens, and even rats may be dangerous to inactive adult specimens in hibernation.

The snakes will exhibit a degree of activity even during hibernation, moving around to keep a body temperature near 5 °C (41 °F) and occasionally emerging to bask on sunny days.

In other parts of the range it has been reported to only use the canopy on a more substantial basis in largely uninhabited areas, such as the natural beech forests of the East Slovak and Ukrainian Carpathians, with similar characteristics.

Rival males engage in ritual fights the aim of which is to pin down the opponent's head with one's own or coils of one's body; biting may occur but is not typical.

The actual courtship takes the form of an elegant dance between the male and female, with anterior portions of the bodies raised in an S-shape and the tails entwined.

The status of the Iranian enclave population remains unclear due to its specific morphological characteristics (smaller length, scale arrangement, darker underbelly), probably pending reclassification.

The common name of the species — "Aesculape" in French and its equivalents in other languages — refers to the classical god of healing (Greek Asclepius and later Roman Aesculapius) whose temples the snake was encouraged around.

The species, along with four-lined snakes, is carried in an annual religious procession in Cocullo in central Italy, which is of separate origin and was later made part of the Catholic calendar.

Though the Aesculapian snake occupies a relatively broad range and is not endangered as a species, it is thought to be in general decline largely due to anthropic disturbances.

[citation needed] In most other countries including France, Switzerland, Austria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Poland, Ukraine and Russia it is also under protection status.

[citation needed] A significant threat also are roads both in terms of new construction and rising traffic, with a risk of further fragmentation of populations and loss of genetic exchange.