Affine geometry

In 1748, Leonhard Euler introduced the term affine[4][5] (from Latin affinis 'related') in his book Introductio in analysin infinitorum (volume 2, chapter XVIII).

In 1827, August Möbius wrote on affine geometry in his Der barycentrische Calcul (chapter 3).

[6] In 1918, Hermann Weyl referred to affine geometry for his text Space, Time, Matter.

He used affine geometry to introduce vector addition and subtraction[7] at the earliest stages of his development of mathematical physics.

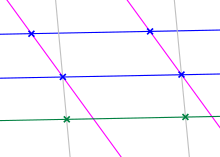

Later, E. T. Whittaker wrote:[8] Several axiomatic approaches to affine geometry have been put forward: As affine geometry deals with parallel lines, one of the properties of parallels noted by Pappus of Alexandria has been taken as a premise:[9][10] The full axiom system proposed has point, line, and line containing point as primitive notions: According to H. S. M. Coxeter: The interest of these five axioms is enhanced by the fact that they can be developed into a vast body of propositions, holding not only in Euclidean geometry but also in Minkowski's geometry of time and space (in the simple case of 1 + 1 dimensions, whereas the special theory of relativity needs 1 + 3).

The extension to either Euclidean or Minkowskian geometry is achieved by adding various further axioms of orthogonality, etc.

In the Minkowski geometry, lines that are hyperbolic-orthogonal remain in that relation when the plane is subjected to hyperbolic rotation.

An axiomatic treatment of plane affine geometry can be built from the axioms of ordered geometry by the addition of two additional axioms:[12] The affine concept of parallelism forms an equivalence relation on lines.

Since the axioms of ordered geometry as presented here include properties that imply the structure of the real numbers, those properties carry over here so that this is an axiomatization of affine geometry over the field of real numbers.

In order to provide a context for such geometry as well as those where Desargues theorem is valid, the concept of a ternary ring was developed by Marshall Hall.

In this approach affine planes are constructed from ordered pairs taken from a ternary ring.

For example, the theorem from the plane geometry of triangles about the concurrence of the lines joining each vertex to the midpoint of the opposite side (at the centroid or barycenter) depends on the notions of mid-point and centroid as affine invariants.

The same approach shows that a four-dimensional pyramid has 4D hypervolume one quarter the 3D volume of its parallelepiped base times the height, and so on for higher dimensions.

This variety of kinematics, styled as Galilean or Newtonian, uses coordinates of absolute space and time.

The shear mapping of a plane with an axis for each represents coordinate change for an observer moving with velocity v in a resting frame of reference.

[15] Finite light speed, first noted by the delay in appearance of the moons of Jupiter, requires a modern kinematics.