Cinema of Africa

Cinema of Africa covers both the history and present of the making or screening of films on the African continent, and also refers to the persons involved in this form of audiovisual culture.

[2][3] Pioneers Auguste and Louis Lumière screened their films in Alexandria, Cairo, Tunis, Susa, Libya and Hammam-Lif, Tunisia in 1896.

[4][5] Albert Samama Chikly is often cited as the first producer of indigenous African cinema, screening his own short documentaries in the casino of Tunis as early as December 1905.

In the first decades of the twentieth century, Western filmmakers made films that depicted black Africans as "exoticized", "submissive workers" or as "savage or cannibalistic".

Examples abound and include jungle epics based on the Tarzan character created by Edgar Rice Burrou, and the adventure film The African Queen (1951), and various adaptations of H. Rider Haggard's novel King Solomon's Mines (1885).

[16] Much early ethnographic cinema "focused on highlighting the differences between indigenous people and the white civilised man, thus reinforcing colonial propaganda".

[18] Marc Allégret's first film,Voyage au Congo (1927) respectfully portrayed the Masa people, in particular a young African entertaining his little brother with a baby crocodile on a string.

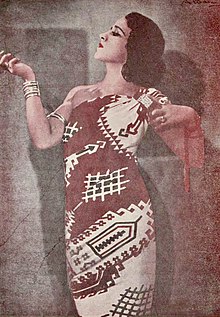

Baker had caused a sensation in the Paris arts scene by dancing in the Revue Nègre [fr] clad only in a string of bananas.

[21] Congolese Albert Mongita did make The Cinema Lesson in 1951 and in 1953 Mamadou Touré made Mouramani based on a folk story about a man and his dog.

[22] In 1955, Paulin Soumanou Vieyra – originally from Benin, but educated in Senegal – along with his colleagues from Le Group Africain du Cinema, shot a short film in Paris, Afrique-sur-Seine (1955).

No less politically engaged than Sembène, he chose a more controversial filmic language to show what it means to be a stranger in France with the "wrong" skin colour.

[citation needed] Souleymane Cissé's Yeelen (Mali, 1987) was the first film made by a Black African to compete at Cannes.

Nigerian cinema experienced a large growth in the 1990s with the increasing availability of home video cameras in Nigeria, and soon put Nollywood in the nexus for West African English-language films.

Contemporary African cinema deals with a wide variety of themes relating to modern issues and universal problems.

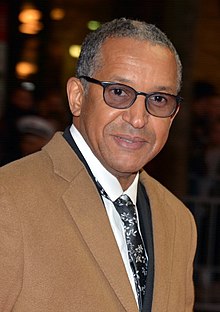

Abderrahmane Sissako's film Waiting for Happiness portrays a Mauritanian city struggling against foreign influences through the journey of a migrant coming home from Europe.

[45] Wanuri Kahiu's short film Pumzi portrays the futuristic fictional Maitu community in Africa 35 years after World War III.

[citation needed] Directors including Haroun and Kahiu have expressed concerns about the lack of cinema infrastructure and appreciation in various African countries.

African film has also been influenced by traditions from other continents, such as Italian neorealism, Brazilian Cinema Novo and the theatre of Bertolt Brecht.

Nearly 10 years after the release of From a Whisper, Kahiu's film Rafiki, a coming-of-age romantic drama about two teenage girls in the present-day Kenya.

Filmmakers often grapple with the portrayal of African cultures, traditions, and modernity, striving to present a narrative that counters the stereotypical depictions seen in Western media.

Films such as "Black Girl" by Ousmane Sembène and "Yeelen" by Souleymane Cissé are examples where African filmmakers use cinema to assert their identity and challenge the dominant narratives imposed by colonial and post-colonial powers.

Despite its growth, African cinema faces significant challenges, including limited funding, distribution difficulties, and competition with Hollywood and Bollywood.

Many African filmmakers struggle to secure financing for their projects, and those who do often face hurdles in distributing their films both within Africa and internationally.

The lack of a robust distribution network means that many African films do not reach a wide audience, limiting their impact and profitability.

Moreover, the dominance of Hollywood and Bollywood films in African markets poses a significant challenge to local filmmakers who must compete for audience attention[60][61] In October 2021, UNESCO published a report of the film and audiovisual industry in 54 states of the African continent including quantitative and qualitative data and an analysis of their strengths and weaknesses at the continental and regional levels.

The report proposes strategic recommendations for the development of the film and audiovisual sectors in Africa and invites policymakers, professional organizations, firms, filmmakers and artists to implement them in a concerted manner.

Apart from the historical developments of audiovisual productions, major filmmakers and their artistic merit and recent trends, such as online streaming, as well as the lack of training, funding, and appreciation of this industry, are discussed.