African military systems (1800–1900)

[3] Some scholars note that the tsetse fly belt which its debilitating effect on load-bearing draft animals, and the presence of terrain such as jungle or brush make extensive use of wheeled conveyances inefficient or impractical.

[8] As the decades rolled on however, improvements to firearms, and other technology such as disease control (the cinchona bark to suppress malaria for example), and steamships were to give Europeans a decisive military edge on the continent.

[9][10] Some European slave-traders and their allies also made use of big canoes in their operations, plying the waterways in heavy vessels backed with musketeers and armed with small cannon, as they collected their human cargo for transport to the Americas.

The landscape also played its part- limiting major, long-term water movement by rivers that were unnavigable for long stretches, contrary currents, and lack of good coastal harbors.

The Fulani, under Usman Dan Fodio, a religious reformer and teacher, suffered a number of initial setbacks against the fast-moving Gobir cavalry, most notably at the Battle of Tsuntua where some 2,000 men were lost.

[14] The cavalry-elites depended heavily for their successes on cooperation with lesser esteemed infantry, who were critical in opening opportunities for attack, fixing an enemy into an unfavorable position, or in suppressing deadly counterfire by poisoned arrows.

Grouped together under competent commanders such as Osei Tutu and Opoku Ware, such hosts began to expand the Ashanti empire in the 18th century on into the 19th, moving from deep inland to the edges of the Atlantic.

In one unusual incident in 1741 however, the armies of Asante and Akkem agreed to "schedule" a battle, and jointly assigned some 10,000 men to cut down trees to make space for a full scale clash.

[27] By contrast, the Zulu retained the effective use of their traditional spears, generally forcing the British to remain in packed defensive formations or entrenched strongpoints, protected by guns and artillery.

As one Western historian observes: The policies of Samori Ture of Mali and Guinea and Abd el-Kader of Algeria illustrate how African states were expanding internally, while fighting foreign invasions.

While small scale raids, skirmishes and revolts always existed, the Algerian anti-French war of the 19th century persisted for decades as a major conflict, with indigenous armies using modern arms to prosecute it.

[28] While unsuccessful, the case of Abd el-Kader illustrates a significant pattern in African warfare that was an alternative to massed "human wave" attacks against small European or European-led forces armed with modern rifles, artillery, and in later years, machine guns (Gatlings and Maxims).

Years of conquest continued and by 1878, he proclaimed himself faama (military leader) of his own Wassoulou Empire, that at its height was to include parts of today's Guinea, Mali, Sierra Leone and the northern Côte d'Ivoire.

Alliances were struck with a number of African polities in this area, particularly the Fulbe (Fula) jihad state of Fouta Djallon, who were facing pressure from the expanding French to submit to a protectorate.

The best known leader to emerge from this flux was the ruthless chieftain Shaka, who adapted a number of indigenous practices that transformed the Zulu from a small, obscure tribe to a major regional power in Southern Africa.

Shaka borrowed and adapted the surrounding cultural elements to implement his own aggressive vision, seeking to bring combat to a swift and bloody decision, as opposed to ritualistic displays or duels of individual champions, scattered raids, or skirmishes where casualties were comparatively light.

The Zulu system spanned both the spear and gunpowder eras and exemplified the typical outcome in Africa when native armies were confronted by European forces armed with modern weapons.

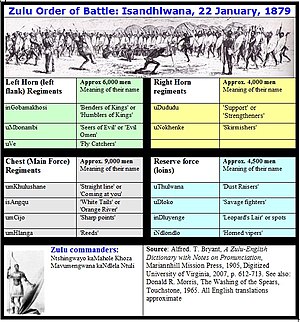

Unlike many other native armies however, the Zulu scored one of the biggest African victories over colonial forces, annihilating a British column at Isandhlawana and almost over-running a detachment at Rorke's Drift.

Poor positioning and deployment of troops, (failure to base the camp on a strong central wagon or laager fortification for example[44] also contributed to fatal weaknesses in the British defences, and the fiery exhortations of the regimental indunas encouraged the host of warriors to continue attacking.

[45] Some recent historians hold that much play was given to the relatively small Rorke's Drift battle to divert attention from the disaster at Isandhlwana where the Zulu clearly outmaneuvered the British, and lured the redcoats into splitting their strength through diversionary actions around Magogo Hills and Mangeni Falls.

[41] Historian John Laband also maintains that the Zulu approach march to the battle was an excellent one, that screened their final movement across the face of the opposition force, and took advantage of Chelmsford's fatal spitting of British fighting strength: Defeat.

Even in the victory at Isandhlwana the Zulu had taken heavy losses,[48] and the efficacy of spears and a few untrained gunmen against modern rifles, machine guns and artillery of a major nation was ultimately limited.

The war put tremendous pressure on the Zulus relatively limited manpower resources, a pattern repeated throughout Africa where comparatively small kingdoms clashed with European states like Britain or France.

The Basotho, a small grouping threatened by the Zulu, Ndebele, as well as the Europeans, adapted to both weapons systems, and carried out a complex mix of warfare and diplomacy to fend off their enemies.

At Adowa, the Italian force, estimated at 18,000 were heavily outnumbered, but had good rifles and some 56 pieces of artillery, and was also stiffened by high quality, elite bersaglieri and alpini units that marched with some 15,000 European soldiers supported by a smaller number of 3,000 African askari.

Ethiopians troops positioned themselves to intercept, and covered by accurate artillery fire, launched a fierce attack that took advantage of this vulnerability, rolling up the Italian line with continuous pressure.

These systems defy the easy categorization and depictions of popular media and imagination- often stereotyped in terms of wildly charging hordes on foot, while ignoring the continent's long established archery and cavalry traditions.

On the waters of the continent, naval activities must be accounted for, not simply canoe transport, but fighting vessels, ports, and troop landings covered by poisoned arrows, bullets and cannonballs.

[68] In the case of the Zulu War, some historians have called it "an unauthorized aggression conducted for reasons of geopolitical strategy" and argue that Britain's main interest was safeguarding the Cape of Good Hope as a strategic base and route to India.

In short, rather than being mere passive actors awaiting colonization, controllers of indigenous military systems were evolving new forms of organization, refining existing ones, or adapting old ones to fit changing opportunities and advanced technology.