Afro–Puerto Ricans

The history of Afro-Puerto Ricans traces its origins to the arrival of free West African Black men, or libertos (freedmen), who accompanied Spanish Conquistador Juan Ponce de León at the start of the colonization of the island of Puerto Rico.

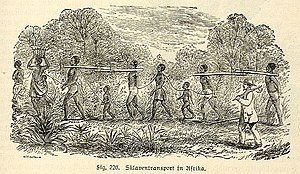

When the Taíno forced laborers were exterminated primarily due to Old World infectious diseases, the Spanish Crown began to rely on sub-Saharan African slavery emanating from different ethnic groups within West and Central Africa to staff their mining, plantations, and constructions.

The need for direct enslaved labor brought through the Atlantic slave trade was greatly reduced by the depletion of gold in Puerto Rico in the 16th century, and the island began to serve primarily as a strategic and military outpost to support, protect, and defend trade routes of Spanish ships traveling between Spain and territories within the continental Americas.

However, the Spanish, hoping to destabilize the neighboring colonies of competing world powers, encouraged enslaved fugitives and free people of color from the non-Hispanic Caribbean to emigrate to Puerto Rico.

As a result, Puerto Rico indirectly received large numbers of sub-Saharan Africans from neighboring British, Danish, Dutch, and French colonies seeking freedom and refuge from slavery.

In 1511, he fought under Ponce de León to repress the Carib and the Taíno, who had joined forces in Puerto Rico in a great revolt against the Spaniards.

After gold mining ended on the island, the Spanish Crown bypassed Puerto Rico by moving the western shipping routes to the north.

The Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 was intended to encourage Spaniards and later other Europeans to settle and populate the colonies of Cuba and Puerto Rico.

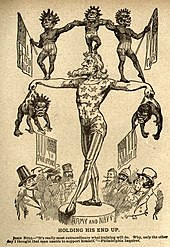

"[24] After the successful slave rebellion against the French in Saint-Domingue (Haiti) in 1803, establishing a new republic, the Spanish Crown became fearful that the "Criollos" (native born) of Puerto Rico and Cuba, her last two remaining possessions, might follow suit.

[28] José Julián Acosta (1827–1891) was a member of a Puerto Rican commission, which included Ramón Emeterio Betances, Segundo Ruiz Belvis, and Francisco Mariano Quiñones (1830–1908).

[29] On November 19, 1872, Román Baldorioty de Castro (1822–1889) together with Luis Padial (1832–1879), Julio Vizcarrondo (1830–1889) and the Spanish Minister of Overseas Affairs, Segismundo Moret (1833–1913), presented a proposal for the abolition of slavery.

[32] The former slaves earned money in a variety of ways: some by trades, for instance as shoemakers, or laundering clothes, or by selling the produce they were allowed to grow, in the small patches of land allotted to them by their former masters.

After emigrating to New York City in the United States, he amassed an extensive collection in preserving manuscripts and other materials of black Americans and the African diaspora.

In 1928, Emilio "Millito" Navarro traveled to New York City and became the first Puerto Rican to play baseball in the Negro leagues when he joined the Cuban Stars.

In 1917, Nero Chen became the first Puerto Rican boxer to gain international recognition when he fought against (Panama) Joe Gan at the "Palace Casino" in New York.

They argue that Puerto Ricans tend to assume that they are of Black African, American Indian, and European ancestry and only identify themselves as "mixed" only if they have parents who appear to be of distinctly different "races".

[63] According to various DNA studies, majority of the African ancestry among black and mixed-race Puerto Ricans comes from a few tribes such as the Wolof, Mandinka, Dahomey, Fang, Bubi, Yoruba, Igbo, and Congolese, correlating to the modern-day countries of Senegal, Mali, Benin, Equatorial Guinea, Nigeria, and Angola.

[68] Many African slaves imported to Cuba, Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico spoke "Bozal" Spanish, a Creole language that was Spanish-based, with Congolese and Portuguese influence.

Island musicians Rafael Cortijo (1928–1982), Ismael Rivera (1931–1987) and the El Conjunto Monterrey orchestra introduced Bomba and Plena to the rest of the world.

What Rafael Cortijo did with his orchestra was to modernize the Puerto Rican folkloric rhythms with the use of piano, bass, saxophones, trumpets, and other percussion instruments such as timbales, bongos, and replace the typical barriles (skin covered barrels) with congas.

[74] Nydia Rios de Colon, a contributor to the Smithsonian Folklife Cookbook, also offers culinary seminars through the Puerto Rican Cultural Institute.

"—Nydia Rios de Colon, Arts Publications Similarly, Johnny Irizarry and Maria Mills have written: "The salmorejo, a local land crab creation, resembles Southern cooking in the United States with its spicing.

The mofongo, one of the island's best-known dishes, is a ball of fried mashed plantain stuffed with pork crackling, crab, lobster, shrimp, or a combination of all of them.

Santería, a Yoruba-Catholic syncretic mix, and Palo Mayombe, Kongolese traditions, are also practiced in Puerto Rico, the latter having arrived there at a much earlier time.

Santería is a syncretic religion created between the diverse images drawn from the Catholic Church and the representational deities of the African Yoruba ethnic group of Nigeria.

Similarly, throughout Europe, early Christianity absorbed influences from differing practices among the peoples, which varied considerably according to region, language and ethnicity.

[79] Considering the 2020 Census is the first to allow respondents to apply multiple races in their responses, there is considerable overlap that while appearing contradictory is in reality reflective of Puerto Rico's mixed history and population.

[82][83] Recent black immigrants have come to Puerto Rico, mainly from the [84] Dominican Republic, Haiti, and other Latin American and Caribbean countries, and to a lesser extent directly from Africa as well.

The municipalities with the highest percentages of residents who identify as black, as of 2020, were:[106] Loiza: 64.7% Canóvanas: 33.4% Maunabo: 32.7% Rio Grande: 32% Culebra: 27.7% Carolina: 27.3% Vieques: 26% Arroyo: 25.8% Luquillo: 25.7% Patillas: 24.1% Ceiba: 23.8% Juncos: 22.9% San Juan: 22.2% Toa Baja: 22.1% Salinas: 22.1% Cataño: 21.8% A landmark study published in 2023 and focused exclusively on studying the genome of self-identified Afro-Puerto Ricans discovered that, as indicated by mitochondrial haplogroups, their average matrilineal lineage is 66% African, 29% Indigenous American and 5% European.

Along the Y chromosome, 52% had African, 28% had Western European, 16% had Eurasian, and, notably, 4% had Indigenous American patrilines, which until that point had been believed to be extinct in the modern population of Puerto Rico.